Previously: “A New World”(1), “A World of Pure Imagination”(2), “Gnosticism: Origins”(3), “Gnosticism: Inversions”(4)

I.

One should place one’s penis into the vagina of one’s mother and one’s sandals on one’s father’s head, while fondling (or licking) one’s sister’s breasts and kissing her fair seat. He who does this, O great Goddess, reaches the abode of Extinction. He who worships day and night an actress, a female skull-bearer, a prostitute, a low-caste woman, a washerman’s wife—he verily becomes identical with the blessed Sada-Shiva (Yoga Karnika)

In the preceding essays, I introduced the “wildly networked mythologies, doctrinal systems, and rituals” of ancient Gnosticism. Here, I’d like to take a broader view and examine the place of Gnosticism within the religious landscape and its relationship to the wider gnostic tradition, that underground stream of mystico-magical culture often referred to, somewhat crudely, as “Western esotericism”.

The gnostic religion in the first centuries CE was an early representative of the esoteric current in Western culture. It is “a mentality, a frame of mind” that can be found in various religious contexts, and is “characterized by the fact that it can easily attach itself to already existing religious or philosophical systems.”

The central idea of a secret Gnosis as a gift that illuminates and liberates man’s inner divinity is found in all periods...For that reason, the terms “Gnosis” and “Gnostic” are applicable to all ideas and currents from Antiquity to the present day that stress the necessity of esoteric spiritual knowledge. (van den Broek, 2006)

This broader view will yield several convergences across cultural space—between Gnosticism and Eastern spiritualities—and time (the various eruptions of gnostic spirituality in the West over the last two thousand years). In what follows, I will review the first category, the often uncanny convergences between Eastern and Western gnostic forms.

II.

Scholars have highlighted several parallels between Buddhism and Gnosticism. Both traditions view material existence as inferior and illusory (māyā). They identify Ignorance (avidyā) as the root cause of entrapment in this world, with liberation hinging on a mystical understanding or 'knowledge' of our existential condition (gnosis or jñāna).

Buddhism and Gnosticism both transcend in their own way the theism/atheism distinction (transtheism). For the former, “The gods exist, but do not count. Even the greatest gods of Brahmanism, Indra and Brahma, are forced to recognise the superiority of the Enlightened One. Without gods and a true ontology, Buddhism can effectively be considered a non-religion or, as is often asserted, an atheist religion.” Similarly, most forms of Gnosticism feature an elaborate hierarchy of deities/angelic beings, however all of these entities are ultimately irrelevant—what “counts” is the ineffable godhead from which they spring. In this same vein, both Christ and Buddha are understood mythically and symbolically, as primordial archetypes instead of deified historical figures.

It seems to me that what Christian theology calls unearned grace, or, in another mode, unconditional love and forgiveness, has been personalized with some bizarrely legalized conceptions of God, but this notion of grace is not so different from what some of the Hindu traditions call liberation from all action or karma, or what some of the Buddhist traditions call emptiness beyond and before every self or thing. Each religious mode, after all, offers utter freedom from the actions and consequences of the socially and historically determined little self. True forgiveness comes, liberation happens, enlightenment shines forth when one side of the Human is set aside, forgotten, outshined for the other side, the Big Self, which is not a self at all. This is what I think the Sinhalese anthropologist Gananath Obeyesekere meant when he observed that the mythos of the Buddha and the mythos of the Christ are structurally the same. They are.

The transtheistic and spiritual attainment-focused nature of both systems lend themselves towards a syncretic openness and independence from ethnonational ties (as opposed to the doctrinal exclusivity and ethnoculturalism of the “bizarrely legalized” Abrahamic religions). Consequently, both systems emphasize classification of individuals by spiritual attainment rather than a simplistic believer/non-believer dichotomy. In Buddhism, there are the puthujjanas, “the worldlings, whose eyes are still covered with the dust of defilements and delusion,” and the ariyans, “the spiritual elite, who obtain this status not from birth, social station or ecclesiastical authority but from the inward nobility of their character”.

These two general types are not separated from each other by an impassable chasm. A series of gradations can be discerned rising up from the darkest level of the blind worldling trapped in the dungeon of egotism and self-assertion, through the stage of the virtuous worldling in whom the seeds of wisdom are beginning to sprout, and further through the intermediate stages of noble disciples to the perfected individual at the apex of the entire scale of human development. This is the Arahant, the liberated one, who has absorbed the purifying vision of truth so deeply that all his defilements have been extinguished, and with them, all liability to suffering.

Compare this to the classification schema of the gnostic Valentinians:

Men who identify with flesh and matter all their lives and cannot tear themselves free, who participate in its existence without in any way lightening its matter, will forever remain hylici, or material men. For them, there is no salvation. Above this are the two circles of Air and Ether, composed of more refined matter, the first step in the climb towards salvation. These circles may be reached by those who have been able to transform matter into psyche by lightening and filtering it, and thus transmuting it sufficiently to create a soul for themselves. This is the second category of human beings: the psychici, the psychic men. But simply to possess a soul is not enough, if this soul is cut off from truth. To perfect oneself, to throw off the ultimate shackles forever, one must know where Truth lies. One must possess gnosis. And here we have the third and certainly the rarest category of human beings: the spirituals or pneumatici, in other words the true Gnostics.

What accounts for these similarities—convergent evolution or cultural exchange? The evidence for the latter is scant and circumstantial; there was some sea trade between the Roman empire and India in the first centuries of the common era, and one of the major centers of Gnosticism, cosmopolitan Alexandria, was home to some Indians. Verardi (1997) argues that the transmission of Buddhist ideas might have been aided by some affinities between the socio-economic base of the two systems: both were were fundamentally urban, mercantile phenomenon existing in societies dominated by great organized powers, the Brahmans in India and the Romans and Catholic church in the West.

The Gnostic communities, and with them the Buddhists, were the optimistic bearers of a model of an open economy and society lacking the defences (and the vexations) of nomos (the laws and institutions of the establishment). It is worth the trouble to observe, as corollary of this position, how both systems opened readily to women. We have spoken of Buddhism; for the Gnostic communities, Rudolph (1977a: 39) has noted how women were offered possibility of self-fulfillment unthinkable elsewhere.

While some degree of influence can’t be ruled out, consider me skeptical. The cultural exchange hypothesis would be more persuasive if antecedents for the similarities didn’t already exist in Western culture; for example, the belief in metempsychosis held by certain Gnostic sects seems to have been passed from Orphism, not Buddhism.

Orpheus, its legendary Thracian founder, is said to have taught that soul and body are united by a compact unequally binding on either. The soul is divine but immortal and aspires to freedom, while the body holds it in fetters as a prisoner. Death dissolves that contract but only to reimprison the liberated soul after a short time, for the wheel of birth revolves inexorably. Thus, the soul continues its journey and alternates between a separate unrestrained existence and a fresh reincarnation around the wide circle of necessity, as the companion of many bodies of men and animals. To those unfortunate prisoners, Orpheus proclaims the message of liberation, that they stand in need of the grace of redeeming gods, Dionysus in particular, and calls them to turn to the gods by ascetic piety and self-purification: the purer their lives, the higher their next reincarnation will be, until the soul has completed the spiral ascent of destiny to live forever as a God from whom it comes.

There is one further domain of correspondence which lends credence to the convergence hypothesis. In the previous essay, we discussed the radical antinomianism of the Gnostics with respect to sexuality and purity codes; though the evidence of ritual orgies and consumption of sexual fluids come down to us only from accusations by Christian heresiologists, the existence of these practices is supported by the fact that certain forms of Eastern spirituality also feature these practices. These transgressive practices and philosophies were, as you might imagine, restricted to more esoteric traditions, and thus highly unlikely to be transmitted across such vast physical and cultural distances.

One such Eastern tradition is Vajrayāna, tantric or esoteric Buddhism, whose rituals include sexual yoga, singing, dancing, and the ingestion of taboo substances such as alcohol, blood, semen, and urine.

Tantric practices focus on transforming poison into wisdom, “one knowing the nature of poison may dispel poison with poison.” Some tantras go further; the Hevajra tantra states “You should kill living beings, speak lying words, take what is not given, consort with the women of others”. While some of these statements were taken literally as part of ritual practice, others such as killing were interpreted in a metaphorical sense. In the Hevajra, “killing” is defined as developing concentration by killing the life-breath of discursive thoughts. Likewise, while actual sexual union with a physical consort is practiced, it is also common to use a visualized consort.

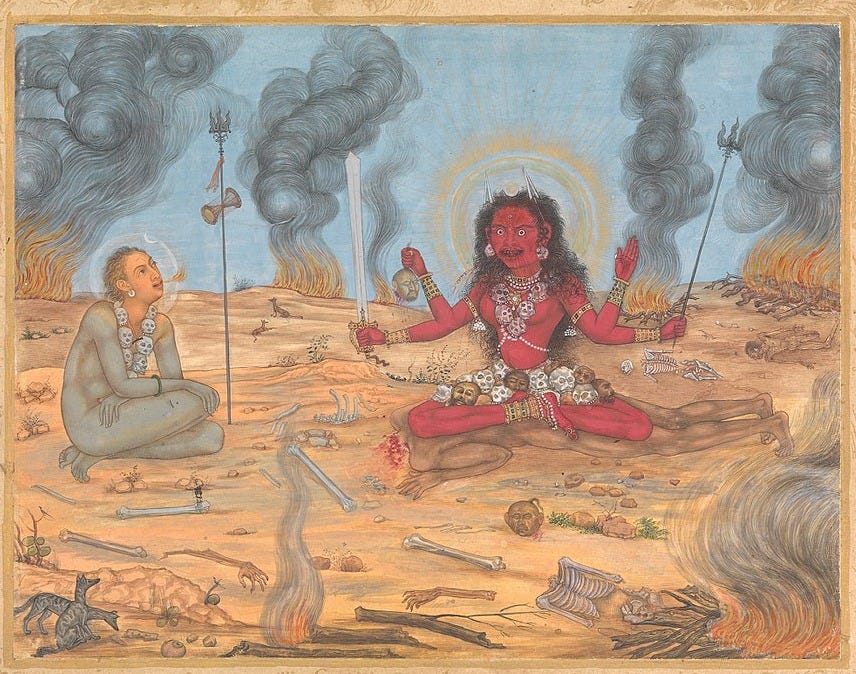

Consider also the Aghori (from Sanskrit: अघोर, ‘dreadless’), a monastic order of ascetic Shaivite sadhus based in Northern India who are the only surviving sect derived from the Kāpālika tradition, a Tantric form of Shaivism which originated in Medieval India between the 4th and 8th century CE.

Aghoris commonly engage in post-mortem rituals, often dwell in charnel grounds, smear cremation ashes on their bodies, and use bones from human corpses for crafting kapāla (skull cups which Shiva and other Hindu deities are often iconically depicted holding or using) and jewellery. They also practice post-mortem cannibalism, eating flesh from foraged human corpses, including those taken from cremation ghats.

An aghori believes that they must go into total darkness in order to find the light…Because of their monistic doctrine, the Aghoris maintain that all opposites are ultimately illusory. The purpose of embracing intoxicant substances, pollution, and physical degradation through various Tantric rituals and customs is the realization of non-duality (advaita) transcending social taboos, attaining what is essentially an altered state of consciousness and perceiving the illusory nature of all conventional categories.

Gnostic antinomianism justifies itself using striking similar notions to those found in Vajrayāna and Aghorism (cf. the bolded passages above to those below).

The idea that in sinning something like a program has to be completed, a due rendered as the price of ultimate freedom, is the strongest doctrinal reinforcement of the libertinistic tendency inherent in the gnostic rebellion as such and turns it into a positive prescription of immoralism. Sin as the way to salvation, the theological inversion of the idea of sin itself… (Jonas)

The Gnostic’s first task was therefore to use up the substance of evil by combating it with its own weapons, by practising what one might call a homeopathic asceticism. Since we are surrounded and pulverized by evil, let us exhaust it by committing it; let us stoke up the forbidden fires in order to burn them out and reduce them to ashes; let us consummate by consuming (and there is only one step, or three letters, between ‘consuming’ and ‘consummating’) the inherent corruption of the material world. (Lacarriere)

III.

Jeffrey Kripal further describes these resonances between Asian tantra and Gnosticism and notes a deep structural pattern found in both Eastern and Western spiritual culture.

Along related lines, it is also worth noting that the gnostic emphasis on salvation by knowledge or mystical insight rather than on faith or obedience to the Law, along with the doctrinal emphasis on transgression, all fit beautifully with the Asian Tantric materials. Following the British Buddhologist Edward Conze, Elaine Pagels has noted the obvious parallels and possible allusions that exist between some of the gnostic materials and certain Hindu and Buddhist ideas (including the very title of the Gospel of Thomas, Thomas being the disciple, according to Christian tradition, who founded a Christian community in India). I am also reminded here of the remarkable gnostic text “Thunder, Perfect Mind”, a profoundly sexualized, deeply paradoxical poem whose very title echoes, like thunder, the kind of language we might find in a Tantric Buddhist tract (note: see below for an excerpt).

Pagels has also observed that the erotic dimensions of the relationship between Jesus and Mary [Magdalene] may point to claims to mystical communion, since sexual metaphors have been used throughout the history of mysticism to express (and, I would add, catalyze) these very types of unitive experience.

I would simply say the same about the alleged sexual practices of groups like the Carpocratians and Phibionites and certain Hindu and Buddhist Tantric texts. Once we have pared away some of the more fantastic and obviously polemical material, what we may be dealing with here is a kind of early Christian Gnostic Tantrism, if I may put it that jarringly. Moreover, and perhaps most important, whether or not any of these groups ever ritually consumed sexual fluids, the rumors, accusations and claims of such acts constitute a powerful witness to the latent mystico-erotic meanings of these same traditions.

Finally, we can also look at these same Gnostic-Tantric echoes structurally. Thanks largely to the work of such scholars as Barbara Holdredge, it is a commonplace among Indologists now to note that there are important structural similarities between Brahmanic Hinduism and Orthodox Judaism. The two religious systems' oral and textual approaches to scripture (Veda and Torah), their profound interest in ritual and sacrifice, and their concern with purity codes have all been noted. This last feature, however, suggests a perhaps hitherto unrecognized structural conclusion: if these two broad religio-social systems display such similar understandings of purity, then we should expect that their “countercultures,” which sought to violate or transgress these same purity ethics (in this case, many of the Hindu Tantric traditions, the early Basileia or “kingdom” movement of Jesus, and some of the early gnostic communities), might also display structural and imaginal affinities, particularly in their use of sexual symbolisms (and likely practices) to effect these same structural transgression. In other words, we might expect early Christian gnostic transgressions and Asian Tantric transgressions to look very similar—and indeed they do.

As I argued in “Gnosticism: Inversions”, this structural transgression was the root and heart of Jesus’ message.

All of Jesus’ inversions and subversions—the first shall be last and the last shall be first, the meek shall inherit the earth, turn the other cheek, “working” (healing) on the Sabbath, his association with prostitutes and lepers, the washing of his disciples’ feet, the very notion that an executed man could be the Messiah—all of these were expressions or manifestations of one basic commandment:

LOVE OVER LAW, LOVE OVER ALL

Excerpted lines from “Thunder, Perfect Mind” (c. 350 C.E.)

I am the first and the last.

I am the honored one and the scorned one.

I am the whore and the holy one.

I am the wife and the virgin.

I am she whose wedding is great

and I have not taken a husband.

I am the bride and the bridegroom

and it is my husband who begot me.

I am the silence that is incomprehensible

and the idea whose remembrance is frequent.

I am the voice whose sound is manifold

and the word whose appearance is multiple.

I am the utterance of my name.

I am the one who has been hated everywhere

and who has been loved everywhere.

I am the one whom they call Life

and you have called Death.

I am the one whom they call Law

and you have called Lawlessness.

I am the one whom you have pursued

and I am the one whom you have seized.

I am the one whom you have scattered

and you have gathered me together.

I am the one before whom you have been ashamed

and you have been shameless to me.

I am she who does not keep festival

and I am she whose festivals are many.

I, I am godless, and I am the one whose God is great.

I am the one whom you have hidden from, and you appear to me.

But whenever you hide yourselves, I myself will appear.

For whenever you appear, I myself will hide from you.

I am control and the uncontrollable.

I am the union and the dissolution.

I am the judgment and the acquittal.

I am unlearned, and they learn from me.

I, I am sinless, and the root of sin derives from me.

I am the one below, and they come up to me.

Hear me in gentleness, and learn of me in roughness.

I am the hearing which is attainable by everyone

and the speech which cannot be grasped.

I am a mute who does not speak

and great is my multitude of words.

It is I who am war, and I who am peace.

I am she who cries out

and I am cast forth upon the face of the earth.

I prepare the bread and my mind within.

I am the knowledge of my name.

I am the one who cries out

and I listen.

For what is inside of you is what is outside of you,

and the one who fashions you on the outside,

is the one who shaped the inside of you.

Hear me, you hearers, and learn of my words.

I am the name of the sound and the sound of the name.

For I am the one who alone exists, and I have no one who will judge me.

For many are the pleasant forms which exist in numerous sins,

and transgressions, and disgraceful passions, and fleeting pleasures,

which men embrace until they become sober and go up to their resting place.

And they will find me there, and they will live

and they will not die again.

Fantastic work, it’s about time we have these analyses, there aren’t enough scholars confronting and dissecting the conversations above our heads and between the cracks. i see the Pneumonia’s pneumonistic conversation and the skatology of the escatology gathering all privy counselors to finally slink into the slimy contagious virility of gnosis. Impeccable timing and i appreciate your practicing immediatism.

Btw where did you get the Yoga-Karnika Translation from? i used one that can be attributed to Georg Feuerstein, PH.D. if you want to cite.