Heresiologists in general use Gnostikoi to indicate those people who belong to a hairesis or schole that deviates from their own Catholic form of Christianity. This pejorative keying of gnöstikoi with hairesis in a deviant sense is a strategic way that heresiologists mark the Gnostics negatively as outsiders and transgressers of Catholic Christianity. The Gnostics were understood by the heresiologists to be so diverse that Irenaeus compares the Gnostics to mushrooms that have sprung up among the Christians.

To understand the New Gnosticism (A New World, A World of Pure Imagination), we first understand the old: why it was born, why it was so radical, and why it was killed.

My (secondary) sources:

The Gnostic Religion by Hans Jonas (1958)

The Gnostics by Jacques Lacarriere (1973)

The Gnostic Gospels by Elaine Pagels (1989)

The Gnostic New Age by April D. Deconick (2016)

In general, I will try to let the authors speaks for themselves—there is no need to reinvent the wheel, especially when the wheel has already been made so round by so many (some of the prose in these books, particularly that of Lacarriere, is also quite lovely and worth sharing for that reason alone).

These secondary sources in turn draw on a number of primary sources, which fall into two broad categories.

The work of early Christian heresiologists. These writings are antagonistic to the Gnostics and therefore unreliable, but in some cases they are the only information we have on a particular sect. Much of what we know about the rituals and practices of the Gnostics comes from these sources; at the end of the next essay, I will address the question of how seriously we should take the more salacious details of these reports.

The Nag Hammadi Library. The vast majority of gnostic texts that have come down to us, were discovered entirely on accident in the eponymous city in Upper Egypt in 1945. The texts date to the 3rd or 4th centuries and are written in Coptic, but most are based on Greek originals from the 1st and 2nd centuries. Many are non-canonical gospels of some sort that paint a very different picture of Jesus’ life and teachings and the origins of Christianity (the Jesus of the Bible is very much the sanitized Hollywood version of Jesus; the Jesus of the Gnostics’ will be discussed in later essays).

Two specific texts are worth mentioning now as I will sprinkle in some quotes from them in my next post (“Gnosticism: Inversions”).

“The Gospel of Thomas is very different in tone and structure from the four canonical Gospels. Unlike the canonical Gospels, it is not a narrative account of Jesus’ life; instead, it consists of logia (sayings) attributed to Jesus, sometimes stand-alone, sometimes embedded in short dialogues or parables; Two-thirds of its sayings and 13 of its 16 parables are found in some form in the canonical Gospels.”

“In other texts often associated with Gnosticism such as the Gospel of Thomas and Gospel of Mary, the Gospel of Philip defends a tradition that gives Mary Magdalene a special relationship and insight into Jesus's teaching. The text contains fifteen sayings of Jesus. Seven of these sayings are also found in the canonical gospels, and two are closely related to sayings in the Gospel of Thomas.”

Origins

Jacques Lacarriere summarizes the core beliefs of Gnosticism.

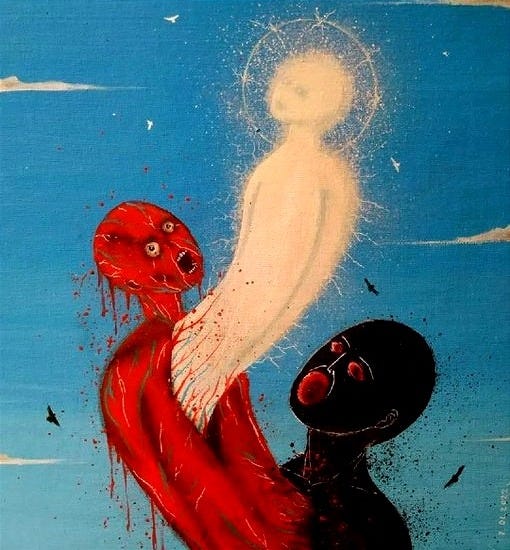

Gnosis is knowledge. And it is on knowledge—not an faith or belief—that the Gnostics rely in order to construct their image of the universe and the inferences they drew from it: a knowledge of the origin of things, of the real nature of matter and flesh, of the destiny of a world to which man belongs as ineluctably as does the matter from which he is constituted. Now this knowledge, born out of their own meditations or from the secret teachings which they claim to have had from Jesus or from mythical ancestors, leads them to see the whole of material creation as the product of a god who is the enemy of man. Viscerally, imperiously, irremissibly, the Gnostic feels life, thought, human and planetary destiny to be a failed work, limited and vitiated in its most fundamental structures. Everything, from the distant stars to the nuclei of our body-cells, carries the materially demonstrable trace of an original imperfection which only Gnosticism and the means it proposes can combat.

But this radical censure of all creation is accompanied by an equally radical certainty which presupposes and upholds it: the conviction that there exists in man something which escapes the curse of this world, a fire, a spark, a light issuing from the true God—that distant, inaccessible stranger to the perverse order of the real universe; and that man’s task is to regain his lost homeland by wrenching himself free of the snares and illusions of the real, to rediscover the original unity, to find again the kingdom of this God who was unknown, or imperfectly known, to all preceding religions.

These convictions were expressed through a radical teaching which held almost all the systems and religions of former times to be null and void. In spite of its links with some philosophies of the time, and apart from minor reservations—since they borrowed certain beliefs indiscriminately from various systems, prophets or sacred books—one can say that Gnosticism is a profoundly original thought, a mutant thought.

In order to appreciate how profoundly original the gnostic mutation was, we must consider the religious milieu in which it first appeared. The spiritualities of the ancient Mediterranean (the Babylonian, Egyptian, and Greek systems) all featured a metaphysical orientation that DeConick describes as “servant spirituality”.

…the human being is the god’s property to do with as the god wishes, even arbitrarily. Gods in these systems typically act as humans might, with emotions and passions that result in capricious and indiscriminate behavior on their part. The sole purpose for the creation of the human being is to produce an entity that will relieve the gods of toil. The human is created to serve the gods, not out of love or respect but out of obligation and fear. If the gods are pleased with the service, the humans may not be punished or destroyed. If the gods are displeased, then famine, pestilence, or war could consume them.

No God exemplified this capriciousness and fear-based rule more than YHWH1, yet Judaism also offered a distinct innovation on servant spirituality: the covenant. No longer could YHWH do as he pleased with his mortal vassals; a treaty was ratified with Abraham and his descendants—if they followed a strict code of law (“Thou shalt have no other gods before me”, dietary restrictions, etc.), then He was obligated to provide them with a homeland, protection, and progeny.

But what if your God doesn’t hold up his end of the bargain—what then?

…Gnosticism emerged from the life experiences of people who were oppressed and had no hope for political advantage. Roman colonialism and imperialism had left them despondent and demoralized. Facing brutal oppression on a daily basis, they began to question the value of their religious upbringing, which taught them to submit to the will of the king as the representative of the gods, to suffer divine retribution for their sins, and to endure the fate the gods had cast for them. And so they rebelled and began searching for a truth beyond the authority of kings and gods, and the first gnostics were born.

This countercultural spirituality was novel and radical, and because of that highly attractive—it was not long before gnostic spirituality went viral, engaging the conventional religions in ways that turned them inside out. This new spirituality migrated into Greco-Egyptian circles of the Hermetics and the Jewish circles of the Sethians. It moved through Palestine, Samaria, and Asia Minor where it interfaced with emergent Christianity in the letters of Paul and the Gospel of John. By the second century, a variety of gnostic thinkers had interacted with Pythagorean and Platonic philosophy, ancient medical knowledge, as well as the craft of ancient astrology and magic. The result of this religious interchange is the emergence of a large number of unique gnostic religious movements with wildly networked mythologies, doctrinal systems, and ceremonies. (Deconick)

As the preceding passage alludes to, ancient Greek spirituality was also a major influence on the Gnostic mutation. In Orphism and the mystery religions we have many of the ideas and practices that would come to characterize Gnosticism: an immortal soul in need of liberation, mysticism, asceticism, and initiatory rites.

The Orphics were an ascetic sect; wine, to them, was only a symbol, as, later, in the Christian sacrament. The intoxication that they sought was that of “enthusiasm,” of union with the god. They believed themselves, in this way, to acquire mystic knowledge not obtainable by ordinary means. This mystical element entered into Greek philosophy with Pythagoras…From Pythagoras Orphic elements entered into the philosophy of Plato, and from Plato into most later philosophy that was in any degree religious. (Bertrand Russell)

Gnosticism has been characterized as an “acute Hellenization of Christianity”, or simply “Platonism gone wild”. Broadly speaking, both Platonism and Gnosticism view life as a form of incarceration (à la the Allegory of the Cave) that can be transcended through psycho-spiritual purification. This purification, or katharsis, leads ultimately to anamnesis: a remembrance of one’s divine nature and origin in the heavenly realm of the Forms, what some gnostics called the pleroma.

The platonic doctrine of emanation and restitution held that the soul has its origin in an eternal, divine substance and will return to it again. The implication was that human beings have an inborn capacity for knowing the divine: they are not dependent on God revealing himself to them (as in classic monotheism, where the creature is dependent on the Creator’s initiative), nor is their capacity for knowledge limited to the bodily senses and natural reason (as in science and rational philosophy), but the very nature of their souls allows them direct access to the supreme, eternal substance of Being. In the science of religion, this inner intuitive ‘knowledge’ is known as gnosis.

(Wouter Hanegraaff)

Gods and Cosmologies

The central and most distinctive feature of gnostic belief is its understanding (or non-understanding) of God. Unlike the god(s) of the aforementioned servant spiritualities, the supreme God of the gnostics is neither the creator nor ruler of our corrupted cosmos. God is absolutely transmundane, utterly remote from creation and hidden from all creatures and perfectly ineffable, “Knowledge of Him requires supra-natural revelation and illumination and even then can hardly be expressed in anything but negative terms”.

The beginning and end of the paradox that is gnostic religion is the unknown God himself who, unknowable on principle, because He is the “other” to everything known, is yet the object of a knowledge and even asks to be known. He as much invites as he thwarts the quest for knowing him; in the failure of reason and speech he becomes revealed; and the very account of the failure yields the language for naming him. He who according to Valentinus is the Abyss, according to Basilides even “the non-being God”; whose acosmic essence negates all object-determinations as they derive from the mundane realm; whose transcendence transcends any sublimity posited by extension from the here, and invalidates all symbols of him thus devised; who, in brief, strictly defies description—he is yet enunciated in the gnostic message, communicated in gnostic speech, predicated in gnostic praise. The knowledge of him itself is the knowledge of his unknowability… (Jonas)

Thou art the alone infinite

and Thou art alone the depth

and Thou art alone the unknowable

and Thou art he after whom every man seeks

and they have not found Thee

and none can know Thee against thy will

and none can even praise Thee against thy will...

(untitled Gnostic hymn)

He-Who-Is is ineffable. No principle knew him, no authority, no subjection, nor any creature from the foundation of the world, except he alone. For he is immortal and eternal, having no birth; for everyone who has birth will perish. He is unbegotten, having no beginning; for everyone who has a beginning has an end. No one rules over him. He has no name; for whoever has a name is the creation of another. He is unnameable. He has no human form; for whoever has human form is the creation of another. He has his own semblance - not like the semblance we have received and seen, but a strange semblance that surpasses all things and is better than the totalities. It looks to every side and sees itself from itself. He is infinite; he is incomprehensible. He is ever imperishable (and) has no likeness (to anything). He is unchanging good. He is faultless. He is everlasting. He is blessed. He is unknowable, while he (nonetheless) knows himself. He is immeasurable. He is untraceable. He is perfect, having no defect. He is imperishably blessed. He is called ‘Father of the Universe’.

(Epistle of Eugnostos)

If the He-Who-Is played no role in Creation, how then was this cosmic prison constructed? Answers vary widely across different sects, but a central mythic structure can be discerned: the world was created by a lowly being descended from the Ineffable One. This being, commonly referred to as the Demiurge (the “craftsman”, a term borrowed from Plato’s Timaeus), was either ignorant of the Father and thought himself to be the highest being, or was malevolently disposed towards Him, and therefore towards us, those fallen beings to whom He gave a share of His divinity.

The leading Gnostics displayed pronounced intellectual individualism, and the mythological imagination of the whole movement was incessantly fertile. Non-conformism was almost a principle of the gnostic mind and was closely connected with the doctrine of the sovereign “spirit” as a source of direct knowledge and illumination. The great system builders like Ptolemaeus, Basilides, and Mani erected ingenious and elaborate speculative structures which are original creations of individual minds yet at the same time variations and developments of certain main themes shared by all: these together form what we may call the simpler “basic myth”. (Deconick)

It may be helpful to consider one specific example of such a mythical narrative. Jorge Luis Borges, who studied the Gnostics and wrote of them factually and fictionally (and whom we might rightly call a modern-day Gnostic), describes the cosmogony of Basilides, an early gnostic leader who is said to have taught in Alexandria from 117 to 138 AD.

In the beginning of Basilides’ cosmogony there is a God. This divinity majestically lacks a name, as well as an origin; thus his approximate name, pater innatus. His medium is the pleroma or plenitude, the inconceivable museum of Platonic archetypes, intelligible essences, and universals. He is an immutable God, but from his repose emanated seven subordinate divinities who, condescending to action, created and presided over a first heaven. From this first demiurgic crown came a second, also with angels, powers, and thrones, and these formed another, lower heaven, which was the symmetrical duplicate of the first. This second conclave saw itself reproduced in a third, and that in another below, and so on down to 365. The lord of the lowest heaven is the God of the Scriptures, YHWH, and his fraction of divinity is nearly zero. He and his angels founded this visible sky, amassed the material earth on which we are walking, and later apportioned it. Rational oblivion has erased the precise fables this cosmogony attributes to the origin of mankind, but the example of other contemporary imaginations allows us to salvage something, in however vague and speculative a form…In the similar system of Satornilus, heaven grants the worker-angels a momentary vision, and man is fabricated in its likeness, but he drags himself along the ground like a viper until the Lord, in pity, sends him a spark of his power. What is important is what is common to gnostic narratives: our rash or guilty improvisation out of unproductive matter by a deficient divinity. (“A Defense of Basilides the False”)

The Alien God

Jonas argues that the “obscure inventions” and “fruitless multiplications” of gnostic cosmologies (and there are some more byzantine than Basilides’) were meant to emphasize the labyrinthe nature of the world.

You see, O child, how many elements, how many ranks of demons, how many concatenations and revolutions of stars we have to work our way through in order to hasten to the one and only God. (Corpus Hermeticum)

In a similar vein, gnostic literature often compares the human condition to that of a stranger lost in a strange land. According to the gnostics, we are aliens in both senses of the word, foreigners and extra-terrestrials, our fundamental experience in this world one of alienation and bewilderment. Our true home, wherein the Father resides (whom Marcion sometimes calls the “Alien God”), is a divine hyper-dimension, utterly transcendent to this fallen realm (i.e. the pleroma).

The alien is that which stems from elsewhere and does not belong here. To those who do belong here it is strange, unfamiliar and incomprehensible…The stranger who does not know the ways of the foreign land wanders about lost; however if he learns its ways too well then he forgets that he is a stranger and gets lost in a different sense by succumbing to the lure of the alien world and becoming estranged from his own origin…The recollection of his own alienness, the recognition of his place of exile for what it is, is the first step back; the awakened homesickness is the beginning of the return. (Jonas)

“Would I rather be feared or loved? Easy. Both. I want people to be afraid of how much they love me.” ―Michael Scott

Cool presentation! The radicality of it is certainly attractive, and I appreciate how well the gnostics respect divine transcendence. The moment some philosophers started to discuss "theodicy", assigning some very definite activities of creation on to their very definite God, and then setting themselves as moral judges to His Actions... has to be the moment where even the possibility of gnosis was long forgotten.

I'm more familiar with the Indian traditions, and they have enough in common with what you just presented, to make one wonder about slow intercontinental exchange of ideas. But I think the Indians mostly ended up putting the error on the side of one's perception; it's not so much that the outer world is evil in itself, but rather that you're seeing it through dirty glasses. I think this difference has pretty serious implications on the kind of attitude to life that each tradition promotes.

Btw if you ever want to go on a weird deep dive, one Hridayartha over at blogspot has been going on for years and years about the dark sides of what he calls gnostic-flavored Buddhism, which includes most of the current Tibetan tradition. About half his posts are in French but there is also plenty of material in English.