The origin story of Valentinus, one of the first and foremost gnostic sages, reads like something out of a comic book.

Valentinus had expected to become a bishop, because he was an able man both in genius and eloquence. Being indignant, however, that another obtained the dignity, he broke with the church of the true faith. Just like those restless spirits which, when roused by ambition, are usually inflamed with the desire of revenge, he applied himself with all his might to exterminate the truth; and finding the clue of a certain old opinion, he marked out a path for himself with the subtlety of a serpent. (Tertullian)

The figure of Valentinus serves as something of a totem for the diametric opposition between the nascent orthodox and the gnostics: each thought the other to be exterminating the truth with the subtlety of a serpent. Yet Gnosticism was not merely a counter-religion defined by its defiance of the One True Christianity, as Tertullian and his fellow Catholics would have you believe. There was in fact a method to the gnostic madness, a coherent spiritual philosophy behind their radically contrarian manner of life.

What Liberates

What liberates is the knowledge of who we were, what we became

Where we were, whereinto we have been thrown

Whereto we speed, wherefrom we are redeemed

What birth is, and what rebirth

The whole of Gnosticism can be found in this Valentinian expression and others like it: true spirituality is not a static blind faith (as it was for the orthodox), but a searching and striving for (self) knowledge.

To seek myself and to know who I was and who and in what manner I now am, that I may again become that which I was. (The Acts of Thomas)

The liberating knowledge which the seeker seeks is something like the following: “We are shards of the divine entombed in rotting cadavers in a rotting cosmos. Our true home, and the ultimate destination to which we speed, is the pleroma, that dimension/condition of perfect fullness/oneness wherein resides the utterly ineffable Alien God.1

This world eats corpses, and everything eaten in this world also dies. Truth eats life, and no one nourished by truth will die. Jesus came from that realm and brought food from there, and he gave life to all who wanted it, that they might not die. (The Gospel of Philip)

Jesus said, “Whoever has known the world has found a corpse. Whoever has found a corpse, of them the world isn’t worthy.” (The Gospel of Thomas, saying 56)

It is, however, not a mere intellectual grasp of this life-eating Truth that the seeker seeks, but a direct mystical communion with It.

This experience of gnosis is knowledge in the most exalted and paradoxical sense of the term since it is knowledge of the unknowable, an experience of the infinite in the finite. By its own testimony throughout mystical literature it unites voidness and fullness, illuminates and blinds. It stands within existence for the end of all existence: “end” in the twofold, negative-positive sense of the ceasing of everything worldly and of the goal in which the spiritual nature comes to fulfillment. (Jonas)

As for how gnosis was achieved, what little is known aligns with the influence of the Greek mystical tradition (Orphism, the mystery religions) and the eclectic-syncretic nature of Gnosticism; prayer, meditation, drugs, ritual, and various ascetic practices were all used in some form or another.

And it is specifically through this struggle against the body’s inertia and the soul’s slumber, by practising techniques of physical and mental awakening, by a sort of long, immense and rational disordering of all the senses—in short, by living a counter-life—that we may triumph over the material and spiritual order of this world. (Lacarriere)

The moral and social life of the gnostic was a logical consequence of this gnosis: how could one be bound by the morals and laws of this world if they are not of this world, if they are Life and the world is death? Indeed, they could not—and so the gnostic sought, “to become so absolutely free that his very existence was an act of rebellion” (Camus—who, along with Sarte, was greatly influenced by Gnosticism).

This metaphysical rebellion manifested in two contrasting ethics, one of ascetic abstention and rejection and another of antinomian transgression and inversion, “a counter-life”.

Was it not their aim, in this domain as in all others, to bring about a total inversion of the values and the relationships between man, his fellow-creatures, and the world? (Lacarriere)

Thus, instead of morality, we have non-morality:

Confronted with the deceptions of reality, the imposture of all Churches and institutions, the mummery of laws, creeds, and taboos, Basilides proposes a very simple morality: non-morality. Thus, at the moment when the first persecutions are beginning against both Christians and Gnostics (the Romans seeing not the slightest difference between the two), he declares that it is natural and necessary to abjure one’s faith in order to escape them. (Lacarriere)

Instead of moral judgement and a postponement of all reward and punishment until after death, we have a salvation that can only be found in life. Deeds and virtues (like the renouncing of one’s faith) are completely irrelevant—only gnosis, and gnosis alone, can save you.

Jesus said, “Look for the Living One while you’re still alive. If you die and then try to look for him, you won’t be able to.” (The Gospel of Thomas, saying 59)

Instead of dogmatic authoritarianism, we have a celebration of “heresy” and the creativity that produces it. The very notion that moral or spiritual Truth could be passed down on high from some authority was ludicrous to the gnostic.

Who administers [spiritual] authority? Valentinus and his followers answered: Whoever comes into direct, personal contact with the “Living One”. They argued that only one’s own experience offers the ultimate criterion of Truth, taking precedence over all secondhand testimony and all tradition—even gnostic tradition! They celebrated every form of creative invention as evidence that a person has become spiritually alive. On this theory, the structure of authority can never be fixed into an institutional framework: it must remain spontaneous, charismatic, and open. (Pagels)

Anti-Heroes

The central theological inversion of the gnostics was discussed in the preceding essay: the God of the Jews and the Christians was not an omnipotent creator-ruler deity, but something more like a petty demon. This counter-theology enraged and flummoxed Christian heresiologists, much to the delight, we can imagine, of the delinquent gnostics.

Yet Irenaeus found it difficult to argue theology with the gnostics: they claimed to agree with everything he said, but he knew that secretly they discounted his words as coming from someone unspiritual…So Valentinians might confess the same creed as a Catholic, “There is one God the Father and everything comes from him, the Lord Jesus Christ.” But the meaning they took from it was different. They were not confessing the Father God to be YHWH. Rather they were confessing the Father God to be the transcendent God… (Deconick)

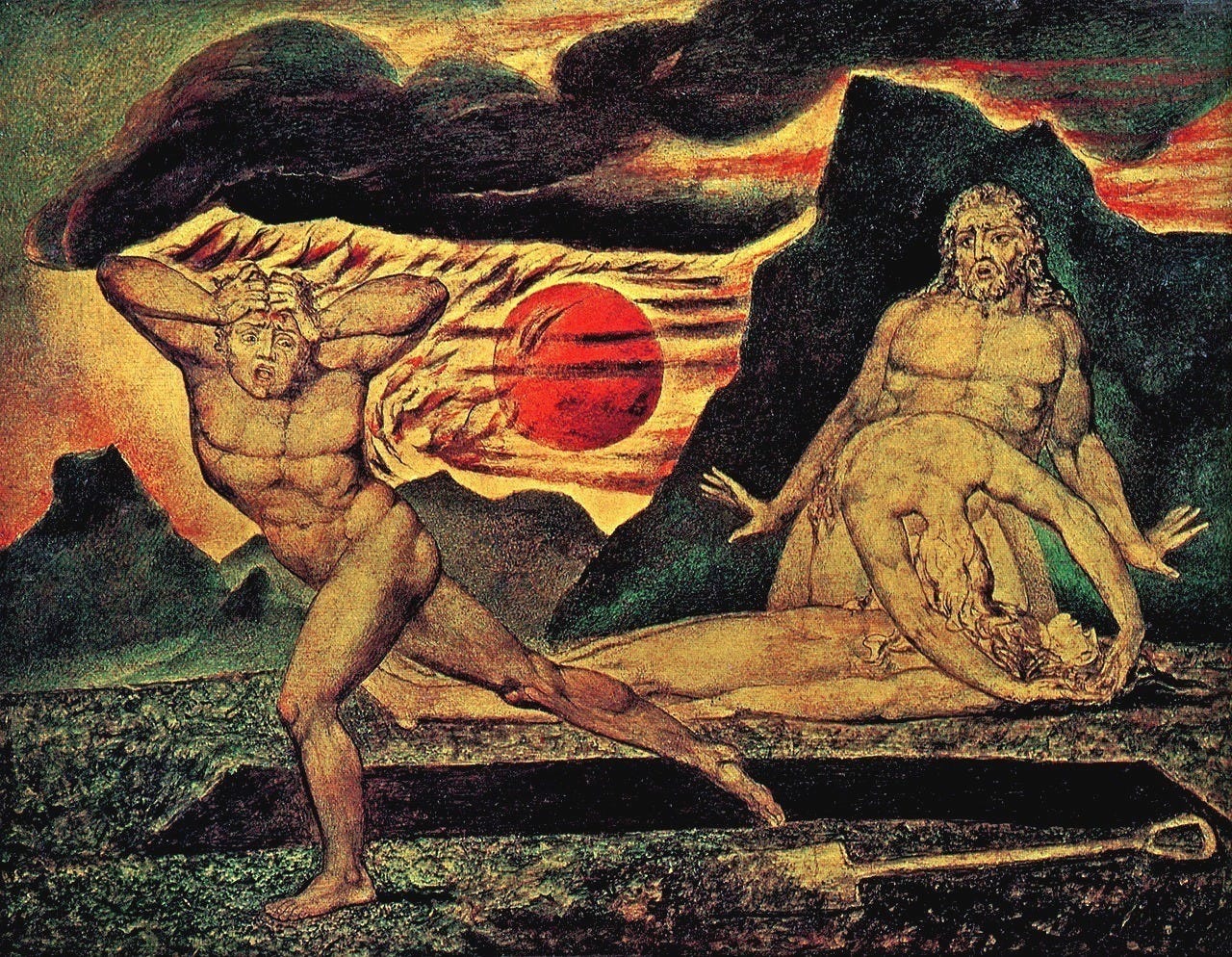

The Gnostics’ antithetical view of YHWH was only the beginning of their contrarianism—virtually all figures whom the orthodox tradition looked upon as damned were venerated by one sect or another. So, for example, the serpent was not Satan or his minion, but a salvific emissary of the Living One, sent to instruct Adam and Eve to eat of the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil—i.e. the Tree of Gnosis.

And the woman said to the serpent, “We may eat the fruit of the trees of the garden; but of the fruit of the tree which is in the midst of the garden, God has said, ‘You shall not eat it, nor shall you touch it, lest you die.’ ” Then the serpent said to the woman, “You will not surely die. For God knows that in the day you eat of it your eyes will be opened, and you will be like God, knowing good and evil.” (Genesis 3:2-5)

The gnostics known as the Ophites (from óphis (ὄφις), ancient Greek for snake) associated the serpent with Jesus, hence their incorporation of the slithering ones into their Eucharist ritual.

The Ophites have a snake, which they keep in a certain chest—the cista mystica—and which at the hour of their mysteries they bring forth from its cave. They heap loaves upon the table and summon the serpent. Since the cave is open it comes out. It is a cunning beast and, knowing their foolish ways, it crawls up on the table and rolls in the loaves; this they say is the perfect sacrifice. Wherefore, as I have been told, they not only break the bread in which the snake has rolled and administer it to those present, but each one kisses the snake on the mouth, for the snake has been tamed by a spell, or has been made gentle for their fraud by some other diabolical method. And they fall down before it and call this the Eucharist, consummated by the beast rolling in the loaves. And through it, as they say, they send forth a hymn to the Father on high, thus concluding their mysteries. (Epiphanius)

There were also the Cainites who venerated their fratricidal namesake because, “he had denied the bond of blood, and thus had become the first to oppose one of the primary alienating laws of this world: the law of the family.”

It would be wrong to conclude from this, however, that the Cainites preached and practiced fratricide. What they undoubtedly venerated in Cain—and, similarly, what the Ophites, the Sethians, and the Peratae venerated in the snake—was an image, a mythical model, an act of rejection whose import was positive for them because it set itself against the order of an evil world at a time when all things were still possible.

As you might expect, The Cainites also held Judas Iscariot in high regard.

They regarded Judas the traitor as having full cognizance of the truth. He therefore, rather than the other disciples, was able to accomplish the mystery of the betrayal, and so bring about the dissolution of all things both celestial and terrestrial. The Cainites possessed a work entitled The Gospel of Judas, and Irenaeus says that he had himself collected writings of theirs.

While it is certain that the Cainites and other gnostic sects applauded Judas’ betrayal, there are differing views on what they saw as his motive. I could share what little is known of these views from the historical fragments that have come down to us, but I feel it would be more in line with the creative spirit of Gnosticism were I to instead share the fictionalized embellishments of these views from Borges’ short story, “Three Versions of Judas” (1944), whom we have already said was himself a modern day gnostic (it is no stretch to imagine the gnostics of old regarding this fiction as evidence of Borges’ spiritual maturity).

The story takes the form of a scholarly article on the books of Nils Runeberg.

In Asia Minor or in Alexandria, in the second century of our faith (when Basilides was announcing that the cosmos was a rash and malevolent improvisation engineered by defective angels), Nils Runeberg might have directed, with a singular intellectual passion, one of the gnostic monasteries.

The first version of Judas:

Skillfully, [Runeberg] begins by pointing out how superfluous was the act of Judas. He observes (as did Robertson) that in order to identify a master who daily preached in the synagogue and who performed miracles before gatherings of thousands, the treachery of an apostle is not necessary. This, nevertheless, occurred. To suppose an error in Scripture is intolerable; no less intolerable is it to admit that there was a single haphazard act in the most precious drama in the history of the world. Ergo, the treachery of Judas was not accidental; it was a predestined deed which has its mysterious place in the economy of the Redemption. Runeberg continues: The Word, when It was made flesh, passed from ubiquity into space, from eternity into history, from blessedness without limit to mutation and death; in order to correspond to such a sacrifice it was necessary that a man, as representative of all men, make a suitable sacrifice. Judas Iscariot was that man. Judas, alone among the apostles, intuited the secret divinity and the terrible purpose of Jesus. The Word had lowered Himself to be mortal; Judas, the disciple of the Word, could lower himself to the role of informer (the worst transgression dishonor abides), and welcome the fire which can not be extinguished. The lower order is a mirror of the superior order, the forms of the earth correspond to the forms of the heavens; the stains on the skin are a map of the incorruptible constellations; Judas in some way reflects Jesus. Thus the thirty pieces of silver and the kiss; thus deliberate self-destruction, in order to deserve damnation all the more. In this manner did Nils Runeberg elucidate the enigma of Judas.

In response to criticism from orthodox theologians, Runeberg modified his doctrine into the second version of Judas:

To impute his crime to cupidity (as some have done, citing John 12:6) is to resign oneself to the most torpid motive force. Nils Runeberg proposes an opposite moving force: an extravagant and even limitless asceticism. The ascetic, for the greater glory of God, degrades and mortifies the flesh; Judas did the same with the spirit. He renounced honor, good, peace, the Kingdom of Heaven, as others, less heroically, renounced pleasure. With a terrible lucidity he premeditated his offense.

In adultery, there is usually tenderness and self-sacrifice; in murder, courage; in profanation and blasphemy, a certain satanic splendor. Judas elected those offenses unvisited by any virtues: abuse of confidence and informing. He labored with gigantic humility; he thought himself unworthy to be good. Paul has written: Whoever glorifieth himself, let him glorify himself in the Lord; Judas sought Hell because the felicity of the Lord sufficed him. He thought that happiness, like good, is a divine attribute and not to be usurped by men

Some five years later, Runeberg quietly released his second book, Den hemlige Frälsaren, in which the third version of Judas was expounded:

The general argument is not complex, even if the conclusion is monstrous. God, argues Nils Runeberg, lowered himself to be a man for the redemption of the human race; it is reasonable to assume that the sacrifice offered by him was perfect, not invalidated or attenuated by any omission. To limit all that happened to the agony of one afternoon on the cross is blasphemous. To affirm that he was a man and that he was incapable of sin contains a contradiction; the attributes of impeccabilitas and of humanitas are not compatible. Kemnitz admits that the Redeemer could feel fatigue, cold, confusion, hunger and thirst; it is reasonable to admit that he could also sin and be damned. The famous text “He will sprout like a root in a dry soil; there is not good mien to him, nor beauty; despised of men and the least of them; a man of sorrow, and experienced in heartbreaks” (Isaiah 53:2-3) is for many people a forecast of the Crucified in the hour of his death; for some (as for instance, Hans Lassen Martensen), it is a refutation of the beauty which the vulgar consensus attributes to Christ; for Runeberg, it is a precise prophecy, not of one moment, but of all the atrocious future, in time and eternity, of the Word made flesh. God became a man completely, a man to the point of infamy, a man to the point of being reprehensible—all the way to the abyss. In order to save us, He could have chosen any of the destinies which together weave the uncertain web of history; He could have been Alexander, or Pythagoras, or Rurik, or Jesus; He chose an infamous destiny: He was Judas.

Transgressive Transmigration (Sexy Sects)

It has come down to us that the gnostic counter-life reached its antinomian apotheosis in the Cainites and related groups, notably the Carpocratians, who saw purposeful, systematic transgression of moral prohibitions as the path to liberation.

The logical outcome of this teaching is clear: in order to rediscover the pure source of desire and of the true Law, the Carpocratians had to violate the false laws of this vile world everywhere and on all possible occasions. Here, immorality is raised to the status of a rational system, total insubordination is lauded as the road to liberation; a Christian author of the time expressed it in these words: “According to them, man must perpetrate every possible infamy in order to be saved.”

This radical doctrine was wedded to a belief in the transmigration of souls (metempsychosis); liberation from the cycle of death and rebirth was not granted to a soul until it had passed through all possible experiences.

So unbridled is their madness, that they declare they have in their power all things which are irreligious and impious, and are at liberty to practise them; for they maintain that things are evil or good, simply in virtue of human opinion…they interpret these expressions, “Thou shalt not go out thence until thou pay the very last farthing,” as meaning that no one can escape from the power of those angels who made the world, but that he must pass from body to body, until he has experience of every kind of action which can be practised in this world, and when nothing is longer wanting to him, then his liberated soul should soar upwards to that God who is above the angels, the makers of the world. (Irenaeus)

By far the most significant moral battlefield, the most highly-charged in terms of outrage, revolt and liberation, was the sexual arena. Though it can’t be regarded uncritically (see the next section), we do have an eye-witness account of the sexcapades of one gnostic sect.

In about the year 335 AD, St. Epiphanius went to Egypt to study the teachings of the Desert Fathers. He stayed first in Alexandria, and it was there that a unique experience befell him, an experience he deplored, but to which we owe our only eye-witness account of a Gnostic sect. Epiphanius was then twenty years old and, it seems, still naïvely innocent. This explains why he saw not the slightest malice in the proposals of several young and pretty Gnostic women who persuaded him that they alone held the key to his salvation. He followed them, was introduced to members of the sect, became familiar with some of their works which he was given to read, and—probably once only—attended a group ritual. The experience was shattering, and the horrified Epiphanius recovered from it with some difficulty, whereupon he ran to the Bishop of Alexandria to denounce the outrageous scenes he had witnessed.

Here is Epiphanius’ account from the Panarion, a compendium of eighty heresies composed in 374 AD (the name translates to ‘bread basket’ or ‘medicine chest’, reflecting the idea that the book was meant to provide remedies against spiritual diseases; later versions are known simply as Adversus Haereses).

Now in telling these stories and others like them, those who have yoked themselves to Nicolaus’ sect for the sake of “knowledge” have lost the truth and not merely perverted their converts’ minds, but have also enslaved their bodies and souls to fornication and promiscuity. They foul their supposed assembly itself with the dirt of promiscuous fornication and eat and handle both human flesh and uncleanness. I would not dare to utter the whole of this if I were not somehow compelled to from the excess of the feeling of grief within me over the futile things they do—appalled as I am at the mass and depth of evils into which he enemy of mankind, the devil, leads those who trust him, so as to pollute the minds, hearts, hands, mouths, bodies and souls of the persons he has trapped in such deep darkness.

But I shall get right down to the worst part of the deadly description of them—for they vary in their wicked teaching of what they please—which is, first of all, that they hold their wives in common. And if a guest who is of their persuasion arrives, they have a sign that men give women and women give men, a tickling of the palm as they clasp hands in supposed greeting, to show that the visitor is of their religion. (hehe)

And the husband will move away from his wife and tell her—speaking to his own wife!—“Get up, perform the Agape with the brother.” And when the wretched couple has made love—and I am truly ashamed to mention the vile things they do, for as the holy apostle says, “It is a shame even to speak” of what goes on among them. Still, I should not be ashamed to say what they are not ashamed to do, to arouse horror by every means in those who hear what obscenities they are prepared to perform. For after having made love with the passion of fornication in addition, to lift their blasphemy up to heaven, the woman and man receive the man’s emission on their own hands. And they stand with their eyes raised heavenward but the filth on their hands and pray, if you please—the ones they call Stratiotics and Gnostics—and offer that stuff on their hands to the true Father of all, and say, “We offer thee this gift, the body of Christ.” And then they eat it partaking of their own dirt, and say, “This is the body of Christ; and this is the Pascha, because of which our bodies suffer and are compelled to acknowledge the passion of Christ.”2

And so with the woman’s emission when she happens to be having her period—they likewise take the unclean menstrual blood they gather from her, and eat it in common. And “This,” they say, “is the blood of Christ.” And so, when they read, “I saw a tree bearing twelve manner of fruits every year, and he said unto me, ‘This is the tree of life’” in apocryphal writings, they interpret this allegorically of the menstrual flux.

But although they have sex with each other they renounce procreation. It is for enjoyment, not procreation, that they eagerly pursue seduction, since the devil is mocking people like these, and making fun of the creature fashioned by God. They come to climax but absorb the seeds of their dirt, not by implanting them for procreation, but by eating the dirty stuff themselves.

But even though one of them should accidentally implant the seed of his natural emission prematurely and the woman becomes pregnant, listen to a more dreadful thing that such people venture to do. They extract the fetus at the stage which is appropriate for their enterprise, take this aborted infant, and cut it up in a trough with a pestle. And they mix honey, pepper, and certain other perfumes and spices with it to keep from getting sick, and then all the revellers in this herd of swine and dogs assemble, and each eats a piece of the child with his fingers. And now, after this cannibalism, they pray to God and say, “We were not mocked by the archon of lust, but have gathered the brother’s blunder up!” And this, if you please, is their idea of the “perfect Passover.”

And they are prepared to do any number of other dreadful things. Again, whenever they feel excitement within them they soil their own hands with their own ejaculated dirt, get up, and pray stark naked with their hands defiled. The idea is that they can obtain freedom of access to God by a practice of this kind.

Man and woman, they pamper their bodies night and day, anointing themselves, bathing, feasting, spending their time in whoring and drunkenness. And they curse anyone who fasts and say, “Fasting is wrong; fasting belongs to this archon who made the world. We must take nourishment to make our bodies strong, and able to render their fruit in its season.”

Did they actually eat aborted fetuses?

Opinions vary on how much we should trust the reports of Epiphanius and his fellow heresiologists. Here is religious scholar Jeffrey Kripal’s take on the matter:

Scholars have debated whether or not such angry texts reflect actual gnostic behaviors or the hateful fantasies of the polemicists themselves. It is certainly true that religions consistently sexualize their heresies as rhetorical ways of stirring up fear and dismissing their religious competitors as perverts: from the early patristic attacks on the gnostic communities to the Malleus Maleficarum and its medieval witches (who were said to gain their magical powers from actual intercourse with the devil), the history of Christian heresy is also a coded history of (male) sexual phobias and fears projected onto the religious other, particularly women.

I certainly do not want to deny any of this, but my comparative senses as all me that we should take these reports about the mystical utility of sexual practices both suspiciously and seriously. Clearly, an author like Epiphanius or Irenaeus is writing to discredit, humiliate, and, if possible, persecute. When Epiphanius, for example, reported what he claimed to know to the church authorities eighteen members of the Phibionites were thrown out. Obviously, we are not dealing with neutral reporting here.

But neither, I think, are we dealing with complete ignorance. Epiphanius’s knowledge may have been polemical and sensationalistic, but it was also unusually intimate and, more interesting still, strangely familiar to the historian of religions. We know, for example, of other texts, which are definitely not polemical, that discuss or at least imagine the consumption of sexual fluids in both China and India. Interestingly, as already noted, the gnostic reading of Jesus and Mary Magdalene as a kind of divine couple to emulate fits well into the numerous theologies and sexual practices of both Hindu and Buddhist forms of Tantra…

At the very least then it is not unreasonable to trust the reports of orgies and sexual fluid consumption.3 But what about the aborted fetuses—did they, in fact, mix them with honey, pepper, and certain other perfumes and spices and fall upon them as beasts?

While the claims of antinatalism (“why bring a creature into the world only to teach him later on that his sole task is to escape from it as swiftly as possible?”) and abortion practices seem plausible given the Gnostics’ disdain for the world, even these are hearsay supported only by Epiphanius’ almost-certainly-biased testimony (as one counter-example, the Valentinians, it seems, did raise families and lead relatively normal lives). To the ears of most religious scholars (and my own), the accusations of fetal cannibalism strain credulity and read as little more than salacious charges meant to generate outrage.

(…and, well, so what if they did?)

Letter vs. Spirit

Yet still the question remains—if not fetal cannibalism, then how far did the Gnostics truly go? Does the doctrine of transgressive transmigration not justify and ratify “the perpetration of every infamy”? First, it should be noted that there is (again) no independent corroboration of this doctrine outside of antagonistic Christian sources, and even in these sources there is no indication of violent or criminal activity amongst the Gnostics. I have focused here on the antinomianism because it is more scandalous and philosophically interesting, but the truth is that the Gnostics likely tended towards asceticism more than anything else and were almost certainly not going around committing iniquities in the name of liberation from samsara. The idea that one must “experience every kind of action” in order to be saved, if it were truly professed, was very likely meant to be understood metaphorically and symbolically, in the same way that venerating Cain as a mythical model was not to be understood as sanctioning senseless fratricide.

The literal interpretation of this teaching by Christian heresiologists speaks to a very deep philosophical difference the orthodox and the gnostics, one that gets to the heart of what it meant to be a gnostic.

Not all gnostics considered themselves followers of Jesus Christ, but those that did differed considerably from the orthodox in their understanding of who Jesus was, what his teachings were, and what it meant to “follow” him. The Carpocratians, for example, “revered Jesus as an ordinary man, excellent in holiness and virtue, whose soul had not forgotten its origins in the higher sphere of the perfect God” and saw him as someone to emulate or even exceed. Jesus was not the only one held in this regard; Pythagoras, Plato, and Aristotle were also held up as figures of veneration. Other gnostics agreed that Jesus was divine, but did not believe him to also be human (how could the perfect spirit of God suffer under the power of matter?). Jesus’ human form, some argued, was only an illusion, a kind of spiritual hologram (docetism); others held that while Jesus did have a material body, his body and his spirit were two separate entities, such that no matter how many pains were inflicted on his body his spirit never suffered (separationism).

The Gnostic text Three Forms of First Thought declares that a divine power “put on Jesus” like a garment. The Second Treatise of the Great Seth has Christ say, “I approached a bodily dwelling and evicted the previous occupant, and I went in.”

This seemingly arcane theological difference had important sociopolitical implications. For the orthodox, those individuals who were closest to the God-Man in his life and to whom He appeared after his resurrection (i.e. the Apostles) were the legitimate leaders of the nascent Church. The gnostics, on the other hand, rejected apostolic succession and the entire notion of spiritual authority, believing it antithetical to Jesus’ teachings. Accordingly, they rejected the literalist interpretation of Christ’s resurrection and virgin birth, seeing them as naive misunderstandings, “the faith of fools”. Those who saw Jesus after his death saw him in visions or dreams; the resurrection was not an event in the past, but something anyone could experience for themselves in the here and now.

One gnostic teacher, whose Treatise on Resurrection, a letter to Rheginos, his student, was found at Nag Hammadi, says: “Do not suppose that resurrection is an apparition [phantasia; literally, “fantasy”]. “Instead,” he continues, “one ought to maintain that the world is an apparition, rather than resurrection.” Like a Buddhist master, Rheginos teacher, himself anonymous, goes on to explain that ordinary human existence is spiritual death, but the resurrection is the moment of enlightenment: “It is…the revealing of what truly exists… and a migration (metabole—change, transition) into newness.” This means, he declares, that you can be “resurrected from the dead" right now: “Are you—the real you—mere corruption?…Why do you not examine your own self, and see that you have arisen?”

Another text from Nag Hammadi, the Gospel of Philip, expresses the same view, ridiculing ignorant Christians who take the resurrection literally, “Those who say they will die first and then rise are in error.” Ironically then, “it is necessary to rise in this flesh since everything exists in it!”.

These doctrinal differences—Jesus as the Son of God vs. a son of God, as literally vs. metaphorically resurrected—supported two fundamentally conflicting religious orientations. For the Catholic orthodox, Jesus and his teachings were the end; one need only obey the letter of the Law (as interpreted and dictated by the clergy) to be saved. But for the gnostics, Jesus and his teachings were simply a means to an end; one need only achieve gnosis and become the Spirit of the Law in order to be saved.

People cannot see anything that really is without becoming like it. It is not so with people in the world, who see the sun without becoming the sun and see the sky and earth and everything else without becoming them.

Rather, in the realm of truth,

you have seen things there and have become those things,

you have seen the spirit and have become spirit,

you have seen Christ and have become Christ,

you have seen the Father and will become Father.

(The Gospel of Philip)

And what is the Spirit of the Law? After elucidating the Carpocratians’ doctrine of transgressive transmigration, Irenaeus writes the following:

And in their writings we read as follows, the interpretation which they give of their views, declaring that Jesus spoke in a mystery to His disciples and apostles privately, and that they requested and obtained permission to hand down the things thus taught them, to others who should be worthy and believing. We are saved, indeed, by means of faith and love; but all other things, while in their nature indifferent, are reckoned by the opinion of men—some good and some evil, there being nothing really evil by nature.

All of Jesus’ inversions and subversions—the first shall be last and the last shall be first, the meek shall inherit the earth, turn the other cheek, “working” (healing) on the Sabbath, his association with prostitutes and lepers, the washing of his disciples’ feet, the very notion that an executed man could be the Messiah—all of these were expressions or manifestations of one basic commandment:

LOVE OVER LAW, LOVE OVER ALL

Previously in this series:

“A New World” (1)

“Gnosticism: Origins” (3)

Epiphanius of Salamis records that The Greater Questions of Mary contained an episode in which Jesus took Mary Magdalene up to the top of a mountain, where he pulled a woman out of his side and engaged in sexual intercourse with her. Then, upon ejaculating, Jesus drank his own semen and told Mary, “Thus we must do, that we may live.” Upon hearing this, Mary instantly fainted, to which Jesus responded by helping her up and telling her, “O thou of little faith, wherefore didst thou doubt?”

A dissenting opinion: “Bart Ehrman, conversely, finds Epiphanius almost entirely unreliable. Ehrman writes that accusing opponents of wild sexual practices was common in Roman antiquity, so Epiphanius’ lurid accounts should be seen as an outgrowth of that…While both their opponents and the gnostics agreed that Gnosticism scorned the material world of the flesh, gnostic writing has generally indicated a trend toward asceticism as a result—of ignoring or punishing the flesh through exertion and fasting.”

Nicely done brother! I’ve been meaning to present this as a circuit, the tantric Yoga-Karnika (ear-ornament of yoga) Shiva says: “One should place one’s penis into the vagina of one’s mother and one’s sandals on one’s father’s head, while fondling (or licking) one’s sister’s breasts and kissing her fair seat. He who does this, O great Goddess, reaches the abode of Extinction. He who worships day and night an actress, a female skull-bearer, a prostitute, a low-caste woman, a washerman’s wife-he verily (becomes identical with) the blessed Sada-Shiva”

Gnostic ritual cuck porn is a masterpiece waiting to happen— Make it so!