Let us imagine that this world were to die.

Not in cataclysm—no, nothing so dramatic—but a slow-motion civilizational collapse, a gradual, even gentle, slip into chaos and madness and darkness.

A death which can not be construed as a series of unfortunate events, but one that is a failure of our failings, our hubris and cowardice, our prejudice and avarice.

A death which makes our existence seem the most Sisyphean affair, an endless hopeless struggle for liberation from the human condition.

Not a physical death, but a philosophical and spiritual death.

Rehearse your death every morning and night. Only when you constantly live as though already a corpse (jōjū shinimi) will you be able to find freedom.

A species absurdly and pathetically ensnared in self-delusion, a twitching spider caught in its own tangled web. Failed beings, an evolutionary abortion.

War, plague, pestilence, starvation, ecological devastation, nuclear winter, the wailing and gnashing of teeth. A world forsaken by its gods.

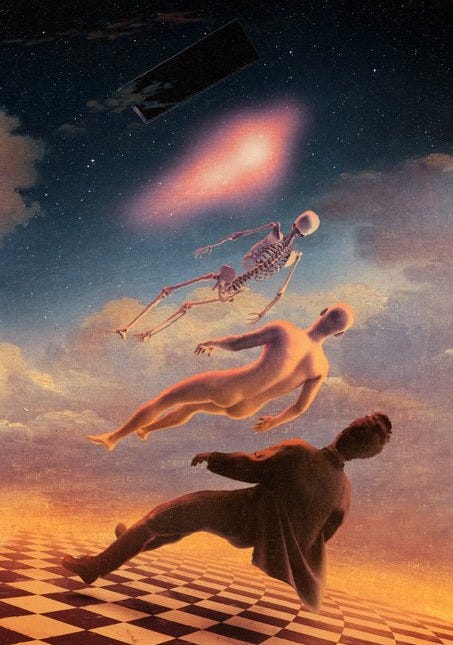

There can be no rebirth without a dark night of the soul,

a total annihilation of all that you believed in and thought that you were.

And what is left when the world has been lost?

That which is not of this world: memory, fantasy, dream, myth.

Like the first law of thermodynamics myths are not created nor destroyed, only altered in form. Myths are eternal in this way: they’ve preceded us and will outlive us too.

Memory is generally considered a subclass of the imagination, as it allows us to picture what is no longer the case or what we are no longer experiencing. Just as our individual sense of identity depends upon how we remember our life (if we lose our memory, we literally no longer know who we are), likewise our sense of collective identity depends upon how we remember our common history. However, our memory is not a photographic plate. Like all other forms of imagination, it is an active faculty that continually recreates the past in the very process of preserving it…

In “Religion and the historical imagination: Esoteric tradition as poetic invention” (2017), Wouter J. Hanegraaff contrasts history (‘what actually happened in the past’) with mnemohistory (‘the history of how we remember the past’) and argues that history in the pre-modern era was as much remembered as it was imagined, as much myth as it was reality.

Historical narratives with a high degree of poeticity tend to be remembered and have an impact on readers even if they are factually inaccurate, while narratives with a low degree of poeticity tend to be disregarded or forgotten even if they are factually accurate.

The Story of Ancient Wisdom, as Hanegraaff calls it, is perhaps the foremost example of a poetical narrative that exerted a powerful influence on history even though it were not entirely factual. Here is how he tells it:

Once upon a time, in very ancient days long before the birth of Christianity, the Light of true spiritual wisdom began to shine in the East. Some say it all started in Egypt, with Hermes Trismegistus; others say it began with Zoroaster in Persia; yet others say that it originated with Moses among the Hebrews. But wherever its ultimate beginning may have been, its true source was God himself, who caused the Light of wisdom to be born in the darkness of human ignorance. The Light now began to spread, carried forward through the ages by a long succession of divinely inspired teachers, until it finally reached Plato and his school in Athens. Now Plato was much more than just a rational philosopher: he was a divinely inspired teacher of wisdom. His dialogues did not present any new and original message either: they merely reformulated the ancient and universal religion of spiritual Truth and Light. Henceforth the true wisdom was carried forward by a succession of Platonic teachers and philosophers, and this tradition finally culminated in the religion of Jesus Christ. When Christianity began to conquer the world, this should have been the glorious fulfilment of the ancient divine revelation. However, something went terribly wrong. The Christian message was perverted and misunderstood. As the Church was triumphant over its opponents, Christians were progressively blinded by power and the pursuit of worldly pleasures. And so, because of their impurity, they slowly lost touch with the ancient core of all true religion. They no longer understood that the gospel was meant to be the culmination and fulfilment of pagan wisdom. Instead, they began to see all pagans as their mortal enemies – practitioners of idolatry and worshipers of demons, dangerous agents of darkness who must be annihilated in God’s name. The Platonic philosophers themselves, and their ancient Oriental predecessors (those who had been the first carriers of the Light) were now perceived as teachers of the dark arts instead. And so it was that the ancient wisdom declined and its true nature was forgotten. There came a time when the leaders of the Church themselves had descended to the level of common criminals, and the very institution of the Church had become an embarrassment to all true Christians. It was at this darkest moment of history, when all seemed lost, that God himself intervened, and after the long darkness of Winter, a new Spring arrived. By the mysterious workings of Divine Providence, the manuscripts of Plato and the ancient teachers of Oriental Wisdom were rediscovered and restored to the light of day. They traveled all the way to Italy, the heartland of the Church, and were translated into Latin and the vernacular languages. Just when they were most needed, due to the miracle of printing, all the sources of ancient wisdom could now be read and studied by the multitudes, more widely than could ever have been imagined at any previous period of time. And so it is that at this darkest moment of decline and forgetfulness, God reminded humanity of the true sources of Wisdom, Truth, and Light. Surely this is the beginning of a new Reformation that will purge the Church of its errors and usher in a New Age of the Spirit. Behold the Golden Times are returning!

Hanegraaff continues:

This is the essential story that Italian humanists such as Marsilio Ficino and his many followers were telling themselves and their readers by the end of the fifteenth century. In discussing such narratives as scholars, we sometimes risk forgetting that we are not just dealing with a theory, a theological doctrine, or an intellectual argument about history – in short, with something that neatly fits our own preferred order of academic discourse. The narrative may contain, or refer to, all those elements; but at the most basic level we are dealing with a story that is meant to speak directly to the imagination and engage the emotions. I want to insist that this is not a trivial observation.

The core narrative of Ancient Wisdom had a very strong impact on the historical imagination of mainstream intellectuals from the fifteenth to at least the eighteenth century, and after its decline in mainstream academic discourse, it has continued to do so in esoteric milieus up to the present. Its remarkable power to influence discourse can certainly not be explained just by the rational arguments or historical evidence that its defenders have tried to muster in support. First and foremost, that power resides in the fact that it is a good story.

He then asks what is so appealing about The Story of Ancient Wisdom—in other words, what are the sources of its poeticity—and settles on two factors:

(1) It is marked by a clear ethical dualism, formulated not just in the somewhat abstract and always debatable terminology of ‘good’ versus ‘evil’ but visualized directly as a battle of Light against Darkness. If the story succeeds in engaging its listeners, they will identify with the Lightbearers who have been working so hard to keep the true knowledge alive, while feeling negative emotions (sadness, defiance, anger) about the forces of darkness and ignorance.

(2) Successive historical events are framed as a journey or adventure through history, in which the protagonists suffer all kinds of setbacks but also experience unexpected moments of salvation. If the story appeals to us, then we are glad to watch the sages carrying on the Light and handing it over to their successors from generation to generation; we are shocked, disappointed, and worried when the mission is betrayed by those who should have known better; we are appalled at the blindness of those who oppose the Light; we feel we want to come to the rescue of the Lightbearers who are so unjustly accused; we feel greatly relieved at the unexpected arrival of help from above; and we are inspired by hope that the forces of darkness and ignorance will not have the final word but the Light will prevail.

If history is the medium of our imprisonment, then history must become the medium of our liberation (to rise, we must push against the ground to which we have fallen).

In order to understand the ideas and currents of thought that will animate the new Renaissance, we must imagine the lived experiences of the underworld men and women. We must imagine what horrors they will have endured, what misery and woe they will have known, how deep and profound their disillusionment. Naturally, there will be some who return, groveling and sniveling, to the religions and ideologies of old, however many will suffer a catastrophic and irrevocable loss of faith in all cultural forms from the Before Times.

It is there, in the hearts and minds of those for whom the world truly died, that a New Life will flower, one animated by a simple, childly logic: if our previous ways of thinking and acting led to the Fall, then let us think and act inversely and reversely that we may Rise.

George Costanza: Why did it all turn out like this for me? I had so much promise. I was personable, I was bright. Oh, maybe not academically speaking, but...I was perceptive. I always know when someone’s uncomfortable at a party. It became very clear to me today, that every decision I've ever made, in my entire life, has been wrong. My life is the opposite of everything I want it to be. Every instinct I have, in every aspect of life, be it something to wear, something to eat...It’s all been wrong.

Jerry Seinfeld: If every instinct you have is wrong, then the opposite would have to be right.

George Costanza: Yes, I will do the opposite. I used to sit here and do nothing, and regret it for the rest of the day, so now I will do the opposite, and I will do something!

The flowering of this counter-life will in turn give rise to a philosophical movement that might be known as Hereticalism, whose core imperative might be expressed as follows: let us resurrect all that was condemned and suppressed; let us raise up what was forced underground; let us revive the thought of those blazing souls whose bodies and books were burned.

From this cultural milieu a new renaissance narrative will emerge and take center stage: If the last two thousand years were dominated by the Christian world-system, then let Gnosticism, Christianity’s long-vanquished arch-nemesis, be the foundation of the next two thousand.

There is one further aspect of the underworld scene that we must consider in order to truly grasp the power of the Gnostic Renaissance narrative. Having lived through the senseless suicide of a global civilization, the disillusionment and disaffection of the underworlders will take on a radical, metaphysical character. They (those who will be the become the bearers of the Light) will feel existence to be a desperate incarceration from which there is no escape.

Man is so fundamentally conditioned by his upbringing, by his social environment, by the temptations of the world, the flesh, and the devil that there’s really nothing he can do to make himself any better. And everything that he does do is simply a manifestation of this same conditioning, like a wolf masquerading in sheep’s clothing. Therefore, if the human being cannot transform himself, if he is to be transformed at all, he must rely on some power greater than his own. (Terence Mckenna)

This, however, is exactly what Gnosticism promises: liberation from the human condition through mystical insight into one’s divine nature (through gnosis).

To the Gnostics of old this world is an immense prison guarded by malevolent powers on high, a place of exile where the fallen and forgetful divine spark dwelling deep within the pneumatikos (the “spiritual man”) languishes in ignorance and bondage, sealed fast within the coarse involucrum of an earthly body. The spiritual experience at the heart of the Gnostic story of salvation was, as Hans Jonas puts it, the “call of the stranger God”: a call heard inwardly that awakens the spirit from its obliviousness to its own nature, and that summons it home again from this hostile universe and back again to the divine pleroma—the “fullness”—from which it departed in a time before time.

Thus the spiritual temper of Gnosticism is, first, a state of profound suspicion—a persistent paranoia with regard to the whole of apparent reality, a growing conviction that one is the victim of unseen but vigilant adversaries who have trapped one in an illusory existence—and then one of cosmic despair, and finally a serenity achieved through final detachment from the world and unshakable certitude in the reality of a spiritual home beyond its darkness. The deepest impulse of the Gnostic mind is a desire to discover that which has been intentionally hidden, to find out the secret that explains and overcomes all the disaffections and disappointments of the self, and thereby to obtain release. It is a disposition of the soul to which certain individuals are prone in any age, but one that only under special conditions can become much more than a private inclination.

There were, so far as we can ascertain, no Gnostic churches or temples in the ancient world. This is no religion for the orthodox or the many, no bowing down to a King or Lord, and hence a metaphysical monarchy in disguise. Rather, Gnosticism is an esoteric religion of the intellectuals, a spirituality for the assertive soul, the unapologetic knower…There is a quality of unprecedentedness about Gnosticism, an atmosphere of originality that disconcerts the orthodox of any faith. Creativity and imagination, irrelevant and even dangerous to dogmatic religion, are essential to Gnosticism. When I encounter this quality in something, I recognize it instantly, and an answering, cognitive music responds in me.

Like circles of artists today, the ancient gnostics considered original creative invention to be the mark of anyone who becomes spiritually alive. Each one was expected to express his own understanding by revising and transforming what he was taught. Whoever merely repeated his teacher’s words was considered immature…On this basis, they expressed their own insight—their own gnosis—by creating new myths, poems, rituals, images, “dialogues” with Christ, revelations, and accounts of their visions…

I'm not sure gnostics would enjoy art that much though. They thought the world was evil; and art, when it's not representing the world, at least exists in the world. It doesn't seem very compatible with extreme asceticism. Christians themselves are a good example according to their level of asceticism. Those catholics who build big cathedrals full of adornments and statues thought the world was good and should be made beautiful. But modern protestants think that "this world" (this material world) is not valuable and therefore build their churches like some ordinary building with no ornaments and no beauty at all.

What if the gnostics and the corrupted world order fall into the same trap that caused the mess in the first place, namely, a separation of the intellect from the corporeal, the idea that our spirit is not this matter, a false dichotomy of subject and object, in a reality where mind, spirit, matter are all bound together in the generative tissue if the cosmos? Two worlds of any kind seems to be falling into the same trap to me.