According to Diogenes Laërtius, Timon of Phlius called Heraclitus “the Riddler” (αἰνικτής; ainiktēs) a likely reference to an alleged similarity to Pythagorean riddles. Timon said Heraclitus wrote his book “rather unclearly” (asaphesteron); according to Timon, this was intended to allow only the “capable” to attempt it. By the time of Cicero, this epithet became “The Dark” (ὁ Σκοτεινός; ho Skoteinós) or “The Obscure” as he had spoken nimis obscurē (“too obscurely”) concerning nature and had done so deliberately in order to be misunderstood.

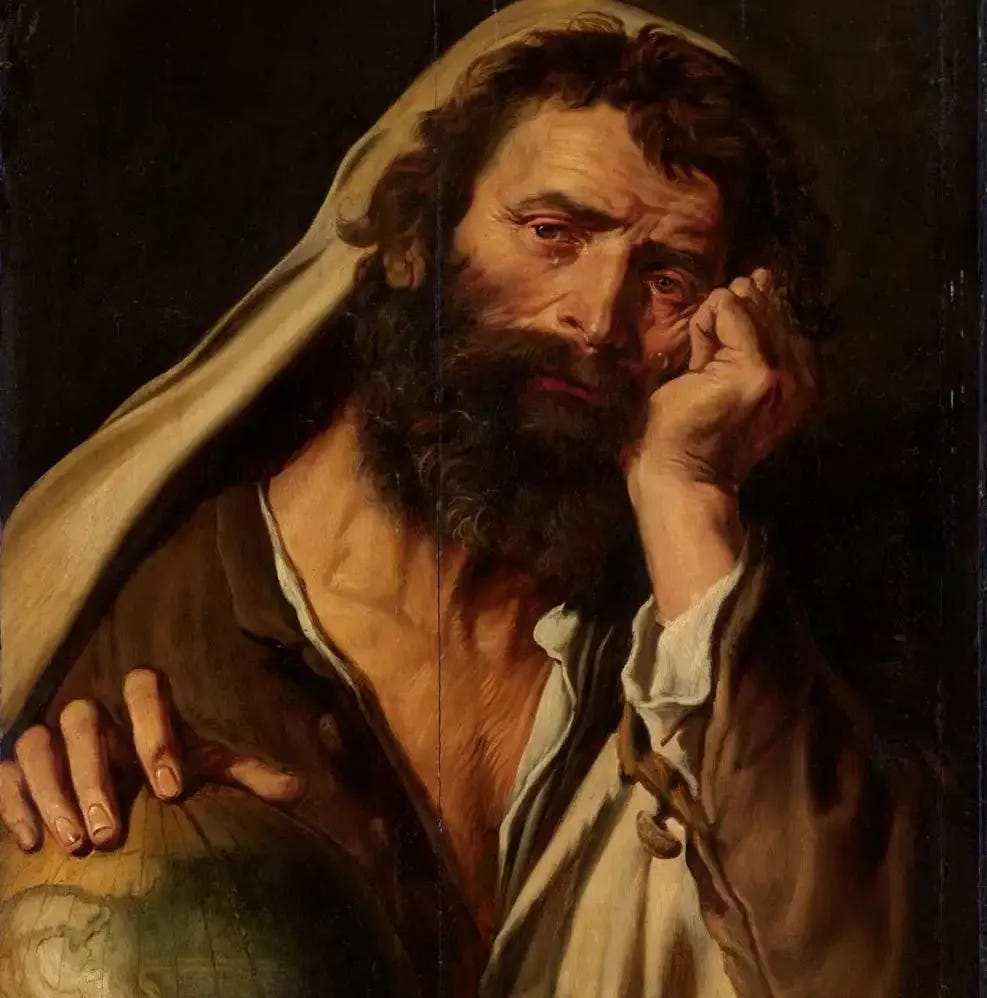

Diogenes Laertius claimed that by the end of his life Heraclitus had become a “complete misanthrope” who had retreated to a hermit-like existence in the mountains.

Apparently suffering from dropsy, a now-obsolete term which defined the accumulation of fluid in the body, he consulted physicians. True to his nature, however, he presented them with a riddle which they didn’t understand, asking “whether they were able to produce a drought after wet weather.”

Taking things into his own hands he tried to cure himself by covering himself in cow dung. It seems that the idea was that the heat from the dung would make the fluid evaporate, but he soon died covered in excrement. Diogenes Laertius goes on to state that according to Neanthes of Cyzicus, Heraclitus got trapped in the dung like quicksand and ended up being eaten by dogs.

The Riddle:

αἰὼν παῖς ἐστι παίζων, πεσσεύων· παιδὸς ἡ βασιληίη

Time is a child at play, moving pebbles; to the child belongs the kingdom.1

A coming-to-be and a passing away, a building up and tearing down, without any moral glossing, in innocence that is forever equal—in this world it belongs only to the play of artists and children. And as the child and the artist plays, so too plays the ever living fire, it builds up and tears down, in innocence—such is the game that the aeon (αἰὼν - life, time) plays with itself.

Transforming itself into water and earth, it builds up towers of sand, like a child making sandcastles by the sea, heaps it all up and then tips it over; from time to time, it starts the game anew. A moment of satisfaction: then need seizes it, as the need to create seizes the artist. Not hubris, but the ever-newly awakening impulse to play calls new worlds into being.2

Notes on the translation of fragment 25:

αἰὼν (aeon) has various meanings—life, time, eternity;

πεσσεύων (peseuōn) is often translated as “playing draughts” or “playing checkers”; it seems to refer to the moving of stone pieces as one would for a game.

Nietzsche

does Heraclitus biopic exist? would love to see one, personally choosing Yorgos Lanthimos to direct.

I've been working on an extended translation of this riddle. It's hard to capture all the aspects in a single line.

I am one.

I am the same.

I am fine.

I am a fool.

If you play—know this: you're with playing notes and stones.

αἰ—oh my.

Does the aeon play eternally?

As long as you play, you are playing.

As long as you play, I play.

As long as you play, you are a player who will win.

As long as all are children, we are playing forever.

To the players who play: the kingdom is a child.

What a player—what a king!

To the one who knows the game: the child is the king.

The kingdom listens clearly.

As a player plays, so plays the cosmos.

As the kingdom plays, so it is ruled.

So who's that playing the piano?

To live and to die—such a passionate realm!

I am a child of this kingdom.

Behold, the queen as its strength.

I am here too.

Suppose the first is the second winner.

Who plays, who passes?

"A child."

To that child belongs the kingdom.

Time is a child at play, moving pebbles.

"And who plays the piano?"

The kingdom as a child.