It pleases the Supreme to reveal His secrets by means of the foolish, who are looked upon by the world as being nothing; so that it may be seen that their knowledge does not come from these fools, but from Him. Therefore I ask you to regard my writings as being those of a child in which the Supreme has manifested His power. (Boehme)

Liber: book; free, unconstrained

Ludens: one who plays

Prediction vs. Prophecy

Problems vs. Games

The Maze

The Dilemma

Gameplay

God

The Journey

Ludus Amoris

The Stage

Deus ex Machina

The Task

Prediction vs. Prophecy

A null hypothesis for our cosmic future:

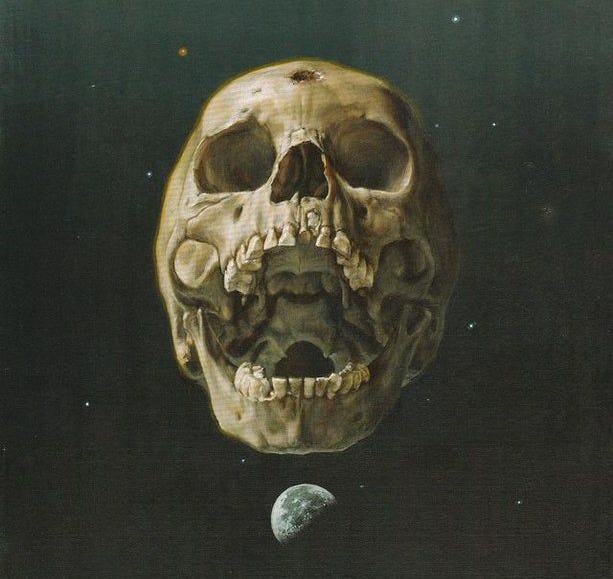

As the number of (biological and/or artificial) agents asymptotes towards infinity, competition will intensify until all “delusions” (art, spirituality, mercy, tolerance, forgiveness, etc.) have been optimized out of existence (see: “Behold the Pale Child”). Also: absolute (technological) power = absolute corruption.

This is the absolute worst possible future; more than anything, it is painfully, painfully boring. Every story ends the same—David lost, Goliath won, forever. The extinction of surprise.

David Deutsch makes a distinction between predictions (extrapolations from current knowledge) and prophecies (claims about future knowledge and creativity, e.g. “that problem cannot be solved”). For example, “earth’s temperature is projected to increase by X degrees by 2060” is a prediction; “the earth’s temperature will increase by X degrees by 2060 and it will be catastrophic for humanity” is a prophecy because it presupposes that we won’t find a way to prevent the projected temperature increase or mitigate its negative consequences.

The null hypothesis is a prediction, not a prophecy. You can’t just crunch the numbers and run the simulation. You have to actually play the game.

Problems vs. Games

Reality is a game masquerading as a problem.

The solution to the puzzle is the act of solving it, since this is play. When you realize this, you understand that in playing, there is no “means-end” — the act is the goal. Just as he once taught us love, he now teaches us to play. There is as great a potential for spiritual significance in play as there is in power, wisdom, love, beauty. (PKD)

Indeed.

Work = usefulness, extrinsicality, adultliness

Play = uselessness, intrinsicality, childliness

It is impossible to distinguish between the two from the outside (e.g. the professional athlete who plays for money/fame vs. the love of the game). Spiritual alchemy is the transmutation of work into play (the saint is one for whom work has been abolished; even the greatest self-sacrifice has become mere recreation).

Although adults attempt to compartmentalize children’s lives into businesslike sections of work and play, children find ways of turning work into play. Life is whole to them, and good, like the creation according to the Genesis story... Unless worship bears connection with what we know to be native to children, it will tend to be sterile, stereotyped, and alien. Look well, therefore, to the meanings of leisure and play, for you may discover the seeds of worship as well.

The Maze

What is this world into which we have fallen?

I think it is a kind of maze.

Epistemologically, all that I really know are negatives: that what we see is not real, and that we cannot by our own efforts outwit the projection machinery. It can serve up one thing after another, ever more cunning and psychomorphic (“I am as you desire me”). We fell into the maze, and the maze is alive; it changes (thus rendering null and void all speculation as to the real nature of the maze)…The maze is alive because it draws on and from the very thoughts of him who is trapped in it; his efforts to solve it are thoughts, and it is these thoughts that “fuel” it.

A strange, shape-shifting maze like a Chinese finger trap: struggle (think, work, fight) and it becomes a problem (you become lost, bewildered); play (explore, imagine, create) and it becomes a game.

Surrender to the maze, embrace the maze, love the labyrinth and those who wander in it and you will win your freedom.

Compassion is the only power capable of solving the maze. This is the essence of Buddhism, the way of the Bodhisattva, the Buddha-to-be (PKD)

I think that what today we call ‘compassion’ may actually be a very high form of intelligence. (Metzinger)

Bodhisattva: Buddhist deity who has attained the highest level of enlightenment, but who delays their entry into Paradise in order to help the earthbound.

The Bodhisattva’s Vow

Sentient beings are numberless; I vow to liberate them.

Delusions are inexhaustible; I vow to end them.

Reality is boundless; I vow to perceive it.

The awakened way is unsurpassable; I vow to embody it.

This means that when you think you are out of the maze — i.e., saved — you are in fact still in it. You only actually get out when you seem to be out, think you are out, and voluntarily decide to return! You have to get outside of the maze to get outside of the maze; hence I say that both the maze (the occlusion) and the solution to the maze are self-winding. So in a sense there is no solution once you are in the maze. In a sense, the solution is (1) impossible; and (2) acausal.

This was to be the theme of Owl in which he is trapped in the maze and only escapes, actually, rather than seemingly, when he decides voluntarily to return (to resubject himself to the power of the maze) for the sake of these others, still in it. That is, you can never leave alone; to leave you must elect to take the others out; thus Christ said, “Greater love hath no man than that he give up his life for his friend”; this is the cryptic utterance of the soul’s solution to the maze, and is the essence of Christianity. Christianity, then, is a system of solution to the maze.

This is what you saw on that balcony, in China, the Chinese gnosis.

Total totalitarianism. The extinction of the human spirit—no longer creatures but units, components. The fleshy cogs of a planetary automata whose sole goal is the perpetuation of its own existence.

There will be no curiosity, no enjoyment of the process of life. All competing pleasures will be destroyed. But always—do not forget this, Winston—always there will be the intoxication of power, constantly increasing and constantly growing subtler. Always, at every moment, there will be the thrill of victory, the sensation of trampling on an enemy who is helpless. If you want a picture of the future, imagine a boot stamping on a human face—forever.

And then you were “told” that you were to construct a labyrinth of thought and feeling and spiritual love which would avert and defeat that future, and you knew that your gnostic-ludic Christianity was to that labyrinth of liberation (“There is no rational way out of the maze, no rigid formula. Rigid formulas are maze constructs”).

There are two ways to win one’s freedom from prison: (1) escape, through brute force or sleight of mind/hand and (2) the transmutation of incarceration into jubilation—i.e. to play so fiercely that life on the inside becomes more free and more joyous than life on the outside, whereupon the “outmates” (the prison guards) will join the inmates and the distinction between inside/outside (between work/play) is dismantled, obliterated, shattered.

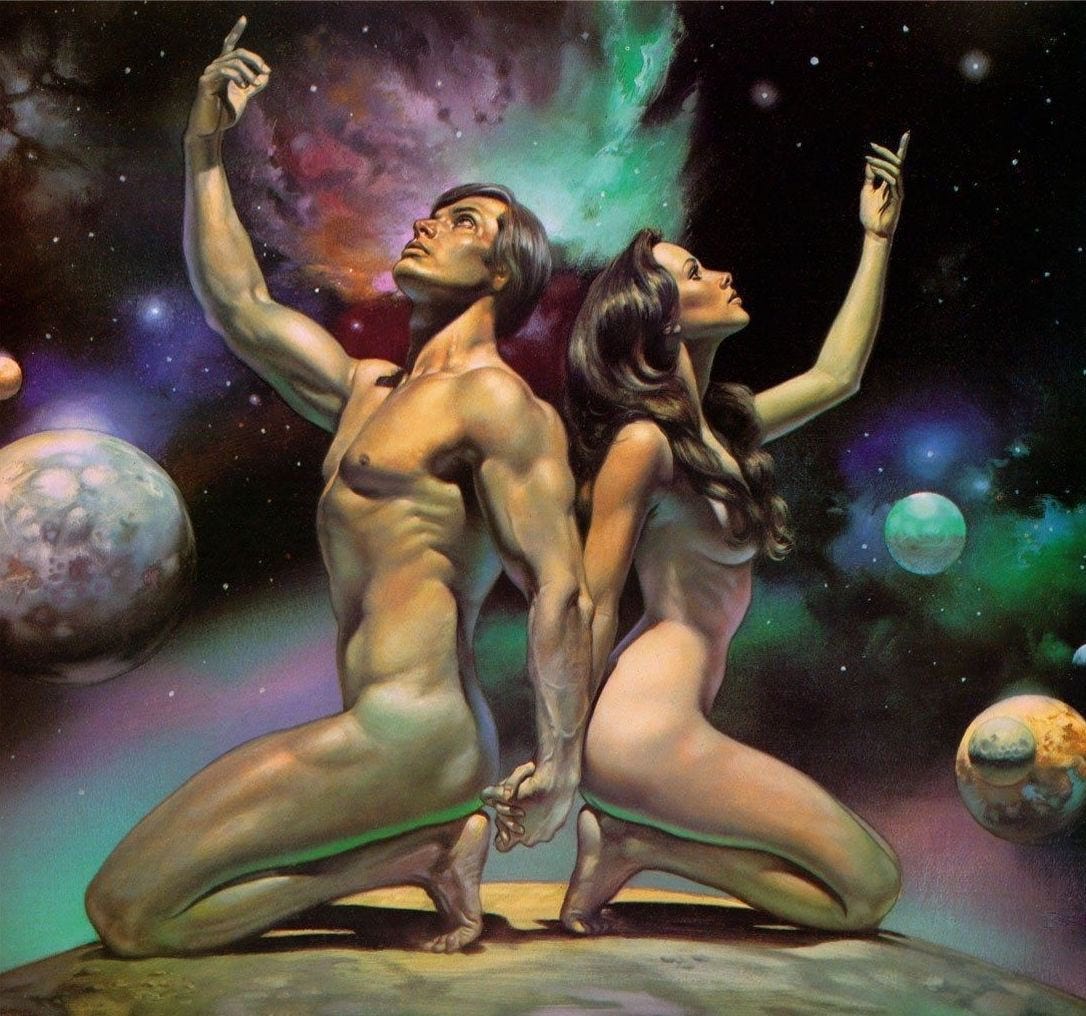

Jesus saw some infants who were being suckled. He said to his disciples: These infants being suckled are like those who enter the kingdom. They said to him: If we then become children, shall we enter the kingdom? Jesus said to them: When you make the two one, and when you make the inside as the outside, and the outside as the inside, and the upper as the lower, and when you make the male and the female into a single one, so that the male is not male and the female not female, then shall you enter the kingdom.

(The Gospel of Thomas, Saying 22)

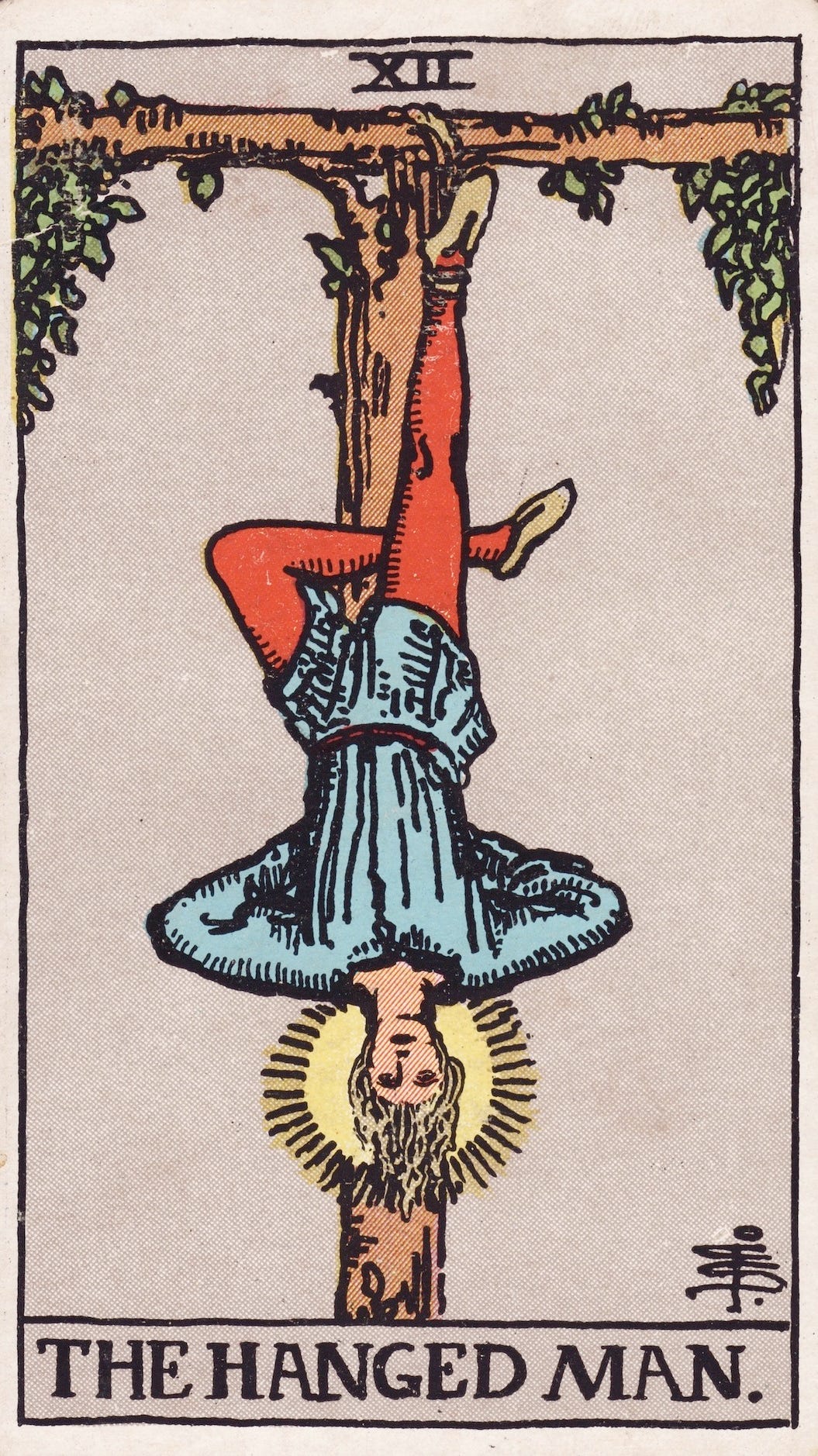

The inversion (the enantiodromia) is the first and most fundamental game-move, the germ from which freedom blossoms (“what if things were the inverse or the reverse of that way which they are now?”). What did Jesus teach but this—the first shall be last, the meek shall inherit the earth, the loving of the enemy, the turning of the cheek, the master is the servant—and what is the Kingdom of Heaven but an eternal game of opposite day? (“These who have turned the world upside down have come here too.”)

Opposite Day is a make believe game usually played by children. Conceptually, Opposite Day is a holiday (a holy day) where things are said and done in an opposite manner. It is not a holiday on any calendar and therefore one can declare that any day of the year is Opposite Day (sometimes retroactively) to indicate something which will be said, or has just been said should be understood opposite to its original meaning.

Hanging is the traditional punishment for traitors. As a metaphysical seeker of wisdom, the Hanged Man is being punished for betraying the material world and asking for more than the mere physical…

When we are born, we see the world upside down. Eventually the mind corrects for this perspective and we come to see the world right side up. Looking upwards and looking within, the Hanged Man sees the world as if a baby, born again.

The Dilemma

As people with chronic diseases when they have despaired of ordinary remedies turn to expiations and amulets and dreams, just so in obscure and perplexing speculations, when the ordinary and reputable accounts are not persuasive, it is necessary to try those that are more out of the way and not scorn them but literally to chant over ourselves the charms of the ancients and use every means to bring the truth to test. (Plutarch)

Our (prisoner’s) dilemma:

Defect/Defect: Hell/Hell

Cooperate/Cooperate: Paradise/Paradise

Cooperate/Defect: (pyrrhic) Victory/Defeat

But this is only a dilemma if you believe that we haven’t already been defeated. In truth, we are already dead. We are shades—spectres, wraiths. This world is the underworld.

Every day when one’s body and mind are at peace, one should meditate on being torn apart by arrows, spears, and swords...You will only find freedom when you live as though already a corpse (jōjū shinimi).

The Hanged Man is likened to a trickster figure who is put in an impossible impasse. It’s not that you’ve made a mistake, it’s that you’re facing a problem that can’t be solved using the normal means. You have to resort to some kind of alien logic in order to find a way out of this situation…

Bostrom makes an offhanded reference to the possibility of a dictatorless dystopia, one that every single citizen including the leadership hates but which nevertheless endures unconquered. It’s easy enough to imagine such a state. Imagine a country with two rules: first, every person must spend eight hours a day giving themselves strong electric shocks. Second, if anyone fails to follow a rule (including this one), or speaks out against it, or fails to enforce it, all citizens must unite to kill that person.

So you shock yourself for eight hours a day, because you know if you don't everyone else will kill you, because if they don’t, everyone else will kill them, and so on. Every single citizen hates the system, but for lack of a good coordination mechanism it endures. From a god’s-eye-view, we can optimize the system to “everyone agrees to stop doing this at once”, but no one within the system is able to effect the transition without great risk to themselves.

There, the final fact of our circumstance: we are utterly helpless, completely and totally incapable of saving ourselves. Salvation must come from beyond the System—from a divine intervention, uncaused, unexpected, and undeserved.

Heidegger: Everything is functioning. That is precisely what is awesome, that everything functions, that the functioning propels everything more and more toward further functioning, and that technicity increasingly dislodges man and uproots him from the earth. I don’t know if you were shocked, but [certainly] I was shocked when a short time ago I saw the pictures of the earth taken from the moon. We do not need atomic bombs at all [to uproot us]—the uprooting of man is already here. All our relationships have become merely technical ones. It is no longer upon an earth that man lives today. Recently I had a long dialogue in Provence with Rene Char—a poet and resistance fighter, as you know. In Provence now, launch pads are being built and the countryside laid waste in unimaginable fashion. This poet, who certainly is open to no suspicion of sentimentality or of glorifying the idyllic, said to me that the uprooting of man that is now taking place is the end [of everything human], unless thinking and poetizing once again regain [their] nonviolent power.

SPIEGEL: Fine. Now the question naturally arises: Can the individual man in any way still influence this web of fateful circumstance? Or, indeed, can philosophy influence it? Or can both together influence it, insofar as philosophy guides the individual, or several individuals, to a determined action?

Heidegger: If I may answer briefly, and perhaps clumsily, but after long reflection: philosophy will be unable to effect any immediate change in the current state of the world. This is true not only of philosophy but of all purely human reflection and endeavor. Only a god can save us. The only possibility available to us is that by thinking and poetizing we prepare a readiness for the appearance of a god.

SPIEGEL: Is there a correlation between your thinking and the emergence of this god? Is there here in your view a causal connection? Do you feel that we can bring a god forth by our thinking?

Heidegger: We can not bring him forth by our thinking. At best we can awaken a readiness to wait [for him].

What does it mean to “prepare a readiness for the appearance of [a] god”? Such a readiness can begin only, I think, with death—the death of our vanity, our pride, our ego.

I am caught in a situation from which there is truly and radically no escape, in a spider’s web I cannot break. If I am to continue to be a living human being, someone must come to free me. In other words, God is not trying to humiliate me. What is mortally affronted in this situation is not my humanity or my dignity. It is my pride, the vainglorious declaration that I can do it all myself. This we cannot accept. In our own eyes we have to declare ourselves to be righteous and free. We do not want grace. Fundamentally what we want is self-justification. (Ellul)

No one likes to help those that insist they do not need help. So the first step is admitting that we cannot break ourselves out of this prison, that we need a (wo)man on the Outside to rescue us.

The (gnostic) Gospel of Philip:

This world eats corpses, and everything eaten in this world also dies. Truth eats life, and no one nourished by [truth] will die. Jesus came from that realm and brought food from there, and he gave [life] to all who wanted it, that they might not die.

The (gnostic) gospel of Dick:

The introjection of Christ into the system is the epitome of the adding of ex nihilo novelty, of revitalizing creation as if from outside. Christ never arises/occurs as a result of the past, as an effect of antecedent causes; he is always born “from outside.” Hence his epiphany can never be induced or predicted (by definition). Christ is that which does not follow mechanically: he always invades the world. Hence where there is Christ it is always the case that there has been “a perturbation of the reality field,” something acting on it, intruding on it “from outside.” Without these periodic insertions the system would run down; it would lose shape, organization and vitality. Cause-and-effect, then, taken in itself, is a losing game. The only thing that Christ can be said to be a result of — Christ as an event in the reality field — is the need of this event. It is physically, mechanically causeless; it is absolutely teleological.

All play moves and has its being within a play-ground marked off beforehand either materially or ideally, deliberately or as a matter of course. Just as there is no formal difference between play and ritual, so the ‘consecrated spot’ cannot be formally distinguished from the play-ground. The arena, the card-table, the magic circle, the temple, the stage, the screen, the tennis court, the court of justice, etc., are all in form and function play-grounds, i.e. forbidden spots, isolated, hedged round, hallowed, within which special rules obtain. All are temporary worlds within the ordinary world, dedicated to the performance of an act apart. (Huizinga)

A game is a world (an ontology, a physics, an ethics).

The world is a game (the world is useless).

To say that Brahman has some purpose in creating the world would mean that it wants to attain through the process of creation something which it is not. And that is impossible. Hence, Brahman has no purpose in making the world. It is created in total freedom and spontaneity, in a state of rapt absorption like that of an artist possessed by his imaginative vision or a child caught up in the delight of a game played for its own sake. This idea is described by the Sanskrit term līlā, which can be translated as Play or Sport.

Worlds, once born, cannot be changed (you cannot work your way to a better world). There are no revolutions, only cosmicides and cosmogonies, only the killing and birthing of worlds through play (recreation = re-creation).

Gameplay

We can, I think, do more than merely preparing a readiness. We can entertain God, and have Him smile upon us for doing so, for even He must pay tribute to the Kingdom of Boredom.

We are here to surprise God. God could make everything, but instead he says, “I bestow upon you the gift of free will so that you can participate in making this world. I could make everything, but I am going to give you some spark of my genius. Surprise me with something truly good and beautiful.”

…So the Creator created creatures because He got tired of playing with himself (heh).

God finds herself in the position not unlike that of a referee. She cannot change the rules of the game, but She can interpret them more or less liberally, and will happily do so if it makes for better gameplay (which is to say: God very much respects the “Rule of Cool”).

The “Rule of Cool” in sports refers to moments when officials overlook minor rule violations because a play is exceptionally exciting or creative in some way. Instead of strictly enforcing the rules, they allow the game to flow in favor of spectacle and fan enjoyment. It’s an unwritten rule where style and entertainment value can sometimes trump technical legality.

Lady Fortune truly does favor the bold, the courageous, the creative, the free in spirit and the pure of heart—those who play the Game the right way, and for the right reasons.

Nature loves courage. You make the commitment and nature will respond to that commitment by removing impossible obstacles. Dream the impossible dream and the world will not grind you under, it will lift you up. This is the trick. This is what all these teachers and philosophers who really counted, who really touched the alchemical gold, this is what they understood. This is the shamanic dance in the waterfall. This is how magic is done. By hurling yourself into the abyss and discovering it’s a feather bed. (McKenna)

What God wants to see from us (and what She rewards, in ways large and small) is a quality we might call “gamefulness” (as opposed to workfulness or jobfulness).

Gamefulness is the serious playfulness (the playful seriousness) that Chapin describes above. It’s sportsmanship, humility, respect for your opponent and for the Game itself (we might say: soreness is given to sore losers, and grace to those who are graceful). It’s playing for the love of the Game and the love of your Team.

It’s an openness to surprise (a surprisefulness), a whimsicality, a tricksiness.

To be playful is not to be trivial or frivolous, or to act as though nothing of consequence will happen. On the contrary, when we are playful with each other we relate as free persons, and the relationship is open to surprise; everything that happens is of consequence. It is, in fact, seriousness that closes itself to consequence, for seriousness is a dread of the unpredictable outcome of open possibility. To be playful is to allow for possibility whatever the cost to oneself.

Surprise in infinite play is the triumph of the future over the past. Since infinite players do not regard the past as having an outcome, they have no way of knowing what has been begun there. With each surprise, the past reveals a new beginning in itself. Inasmuch as the future is always surprising, the past is always changing. (Carse)

Gamefulness is many things, but perhaps more than anything it is the ability to see the games of life as such, and be able to walk away from these games when they no longer serve Life (freedom, possibility, growth, evolution, love).

Now, the nature of the game—I think I’ve told some of you this before, but I see some I haven’t—the nature of the game is: let us pretend that the positive and the negative are not really identical. You see, they’re explicitly different but implicitly the same, because they always go around together. And that reveals a hidden, implicit conspiracy between black and white, and the truth is you can’t have one without the other. But if we can pretend that they don’t go together, that they are actually enemies, then we can have all sorts of games. The first game of which is: oh dear, black might win! The next game is: but white must win! And from that position you can develop all the games you want. And it’s interesting, isn’t it, how so many of our table games—like chess and dominoes and checkers and so on—use the black and white pieces. And you can find, in the conventions of chess—one could discuss all this problem in terms of chess.

Cooper: I know the moves I’m supposed to make, and I know the board.

Roger: So…

Cooper: I’ve been doing a lot of thinking lately and I've started focus out beyond the edge of the board, at a bigger game.

Roger: What game?

Cooper: The sound the wind makes through the pines, the sentience of animals. What we fear in the dark and what lies beyond the darkness…

Roger: What the hell are you talking about?

Cooper: I’m talking about seeing beyond fear, Roger, about looking at the world with love.

Roger: They are liable to extradite you for murder and drug trafficking!

Cooper: These are things I cannot control…

(video)

As long as you stick to the flat chess board, you are in a zero-sum game. If the white players win, the black players lose. If the black players win, the white players lose. The whole thing is set up for an either-or outcome. But what if one moves up into a third dimension and ceases to identify with the pieces of either side on the two-dimensional chessboard? What if one recognizes the game as a game and just walks away?

We almost walked away once.

The Germans placed candles on their trenches and on Christmas trees, then continued the celebration by singing Christmas carols. The British responded by singing carols of their own.

The two sides continued by shouting Christmas greetings to each other. Soon thereafter, there were excursions across No Man’s Land, where small gifts were exchanged, such as food, tobacco, alcohol, and souvenirs such as buttons and hats. The artillery in the region fell silent. The truce also allowed a breathing spell where recently killed soldiers could be brought back behind their lines by burial parties. Joint services were held. In many sectors, the truce lasted through Christmas night, continuing until New Year's Day in others. By some estimates, over a 100,000 soldiers participated in the truce.

Famously, a football match broke out between the two sides.

Lieutenant Kurt Zehmisch of the 134th Saxon Infantry Regiment said that the English “brought a football from their trenches, and pretty soon a lively game ensued. How marvellously wonderful, yet how strange it was”.

A World War ground to a halt because both sides believed that a God-man was born on the 25th of December. Yes, the fighting eventually resumed, but it could not have—they could have just kept playing. They could have kept the match going indefinitely (infinitely), they could have expanded the match until every single soldier on both sides was playing and not warring and the field was the entire Earth and they could have decided that every day was a holy day (an opposite day) and instantiated the Kingdom of Heaven then and there on that very day.

God

There is a ludic dimension (līlā) and a dramatic dimension—a world is a game is a story. The comedy and tragedy in reality is a reflection of the comedy and the tragedy within God’s soul.

Many myths express the coincidentia oppositorum in the very nature of the divinity, which shows itself, by turns or even simultaneously, to be benevolent and terrible, kind and wrathful, creative and destructive, and so on.

The only god of which I can conceive—the only god that makes sense—is a god of paradox, a god who is everything everywhere forever and nothing nowhere never, a god who is transcendent and immanent, personal and impersonal, unity and multiplicity, stillness and movement, a god who is dual and nondual.

I am time without end. I am the sustainer. My face is everywhere. I am the death that snatches all. I am the source of all that shall be born. I am glory, prosperity, beautiful speech, memory, intelligence, steadfastness and forgiveness. I am the dice play of the cunning. I am the strength of the strong. I am triumph and perseverance. I am the purity of the good. I am the silence of things secret. I am the knowledge of the knower. I am the divine seed of all that lives. In this world nothing animate or inanimate exists without me.

Like Dick, I take much from Jakob Boehme:

[Boehme’s] understanding of God was to the highest degree dynamic. Christian theological systems, however, have worked out their teachings about God, employing categories of thought from Greek philosophy. Thus, the teaching about God, as pure act, comprising within Him no sort of potentiality, was constructed wholly upon Aristotle. The teaching about the unstirring, self-sufficient, static God of Christian theology was taken not from the Bible, not from the Christian Revelation, but from Parmenides, Plato, Aristotle. Within it was reflected the static aspect from Greek ontology. The predominant theological doctrine deprives God of inner life, denies any sort of process within God, makes Him equivalent to an unstirring stone. This idea is blasphemous, for the God of the Bible is full of inner life and drama—a tragic God, undergoing the torment and sufferings of the Cross; a compassionate God, offering the sacrifice of love; a dynamic God, who moves and is moved.

A summary of Boehme’s revelation:

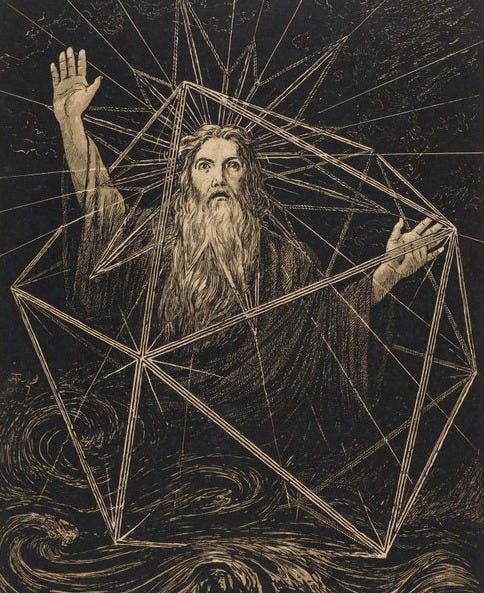

It all started one day around 1610; a young German shoemaker was looking at a pewter dish when a dazzling ray of reflected sunlight unexpectedly turned out to be a message from God…

…Prior to the creation of man God was an undifferentiated single unity defined by the absence of everything else—the Abyss, or “Ungrund”. Creation was the result of the Ungrund dividing from its state of original unity—a proposition completely familiar to Taoists but foreign and offensive to Böhme’s fellow Lutherans.

Even more controversially, Böhme argued that God could not be omniscient and omnipotent, since He was eternal and unique. “He knows no beginning, and also nothing like Himself, and also no end,” Böhme wrote, arguing that God created man in His own image so that He could learn about Himself.

To initiate this learning process, God rendered Himself into positive and negative aspects (c.f. yin and yang to the Taoists). Prior to the initial split, God was only a potential mind with an unformed longing to know itself. After the split, God iterated into a binary-based matrix, continually increasing in complexity as He collected more and more information about Himself. In other words, Böhme’s God evolves with the passage of time, in sharp contrast to the traditional Judeo-Christian view of a perfect, complete and unchanging figure who exists outside the normal flow of time.

The positive and negative aspects of creation were necessarily opposed to each other, and Böhme believed that this conflict was at the heart of the universe's logic and all of its processes. Since this tension is inherent to the design of all reality, evil and suffering are a necessary part of reality—and both originate with God.

The tension between God’s positive and negative aspects boils down to an identity crisis—cosmic self-loathing. The positive force is the part of God that chose to differentiate itself in search of self-knowledge; the negative force is the part of God that seeks to return to its original unified state (obliterating reality in the process). Böhme characterized this negative force as “divine wrath,” the eternal frustration of seeking a goal that can never be accomplished.

So it is something like this: God finds himself existing, but doesn’t know who He is, what He is, or why He is. In this existence there is despair, fear, loneliness, and, perhaps most of all, boredom. God’s attempt to heal this existential wound through self-understanding is the source of the everything always-evolving everywhere all at once forever (the world is a solution to a problem; it is work).

And yet God is, at the same time, omnipotent and omnibenevolent and absolutely self-sufficing. The world is a comedy (a game), created in absolute freedom for no reason whatsoever, an effusion of divine uselessness (it is play).

Theology however operates primarily through concepts, especially the Catholic school theology, so beautifully worked out. I term it a comedy, this following conception from the kataphatic rational theology: God is perfect and unstirring, omniscient, all-powerful and all-good; He created the world and man for His own glorification and for the good of the creation; the act of the world-creation was neither evoked by nor answered any sort of need in God, it was the product of free chance, and no-wise added up to anything more for the Divine being and no-wise enriched it.

Boehme was one of the few bold enough to rise above this rational kataphatic theology and to perceive the mystery of the world-creation as a tragedy and not as a comedy. He teaches about a process not only cosmogonic and anthropogonic, but also theogonic. But the theogony does not at all signify, that God has a beginning, that He arises within time; it does not mean, that He comes about to be within the world process, as with Fichte or Hegel. It signifies that the inner eternal life of God reveals itself as a dynamic process, as a tragedy within eternity, as a struggle with the darkness of non-being.

Nietzsche speaks here of man but he might also have spoken of God.

There is a profound illusion which first entered the world in the person of Socrates: the unshakeable belief that rational thought, guided by causality, can penetrate to the depths of being, and that it is capable not only of knowing but even of correcting being. This sublime metaphysical illusion is an instinctual accompaniment to science, and repeatedly takes it to its limits…But now, spurred on by its powerful illusion, science is rushing irresistibly to its limits, where the optimism essential to logic collapses. For the periphery of the circle of science has an infinite number of points, and while it is as yet impossible to tell how the circle could ever be fully measured, the noble, gifted man, even before the mid-course of his life, inevitably reaches that peripheral boundary, where he finds himself staring into the ineffable. If he sees here, to his dismay, how logic twists around itself and finally bites itself in the tail, there dawns a new form of knowledge, tragic knowledge, which needs art as both protection and remedy, if we are to bear it.

In “Ariadne auf Naxos”, the opera by Richard Strauss, a rich man in Vienna plans a splendid party. First a solemn tragedy is to be performed and then a comedy, and to conclude, there is to be a magnificent display of fireworks. But the director of the tragedy is displeased that his serious work will be followed by clowning and buffoonery, and things get even worse when the rich man’s major-domo tells him that the fireworks must start at nine o’clock sharp, so the tragedy and the comedy will have to be played at the same time. And so that is what happens: the tragedy unfolds with the clowns in its midst.

With a narrative twist that is peculiar to Ismaili theology, their cosmology adds here a ‘pathetic’ element (from pathos, feeling): the Divinity, God in its state as pure essence and pure existence, is traversed since His origin by a profound sentiment. God feels the sadness of an abyssal loneliness: entirely coincident with existence as such, God has no one to whom He can relate—He doesn’t even have an image of Himself that He can contemplate.

To escape His original state of non-relationality, God emanates the angelic figures out of Himself. Ismaili angels stand towards God as the image of something that is, in itself, beyond any possible figuration, Their position is paradoxical and it can only be rendered, somehow, through a vague series of metaphors—such as, for example, the comparison in Ishraqi literature of the angelic figures with the colours that are projected by a colourless beam of light traversing a prism.

Acting as a mirror, the angel of the world offers to God the possibility to see a reflection of His own image, and thus to break the crushing loneliness that marred His original state of absolute non-relationality.

According to Ismaili prophetic philosophy, everything within the range of experience and of perception has to be interpreted as an angel of sorts—including the world, which is perhaps the largest angel in the host. (Campagna)

I remember my grandfather telling me how each of us must live with a full measure of loneliness that is inescapable, and we must not destroy ourselves with our passion to escape the aloneness. (Jim Harrison)

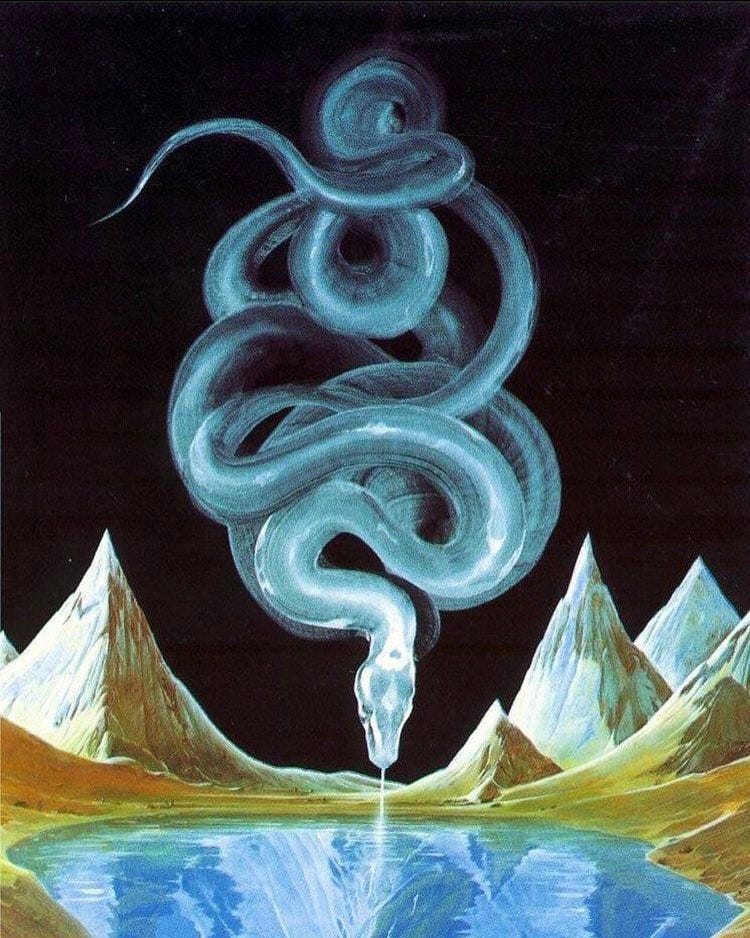

Atum is pictured in the oldest layer of Egyptian mythology as the single God above and beyond the world and the deities who populate it. He is the self-created God who came into being alone within the primal waters of chaos, Nun (Assmann 2001, 177, 180). The Egyptian Coffin Texts describe the cosmos coming into existence as an act of Atum coming to an awareness of his self, making a transition from lying inert and weary in primeval water to becoming conscious and active. Atum stands up on a mound, or he begins to writhe around as a serpent in the primal ocean, encircled in his own coils.

As Atum gains awareness and comes into being, he is called by the name Kheprer, which means “The One Who Comes into Being” (Pyramid Texts 1587). Kheprer consequently manifests himself in the cosmos as Rê, the sun god who rises every morning. What happens when Atum is brought to consciousness and realizes his aloneness? He must diversify or go mad in the total isolation. For the first time, he experiences the erotic, the desire for others, and has an erection. “I am the one who came into being as Atum,” he says. “It was in Heliopolis that my penis became erect. I grasped hold of it and came to orgasm. Thus it was that the siblings, Shu and Tefnut, were born” (Pyramid Texts 1248).

But how were they born? The ancient Egyptians pictured Atum as a hermaphrodite whose mouth is his womb. He creates through a sexual process of autogenesis, where he inseminates his own uterine mouth. His offspring are differentiations of himself, one male and the other female. In the speeches of the Coffin Texts, Atum is shown to be the primeval hermaphrodite who creates his children, Shu, the god of air and Tefnut, the god of moisture, when he spits them out of his mouth in a great exhalation or a roar. Shu, whose own breath eventually enlivens the human body, is the manifestation of life, while Tefnut is the manifestation of maat (truth).

This is the beginning of creation, initialized by Atum, the God Who Made Himself into Millions. He is the One and All. He is the supergod over all other deities, whose name and figure are hidden (Assmann 2001, 240-243), He is the undifferentiated unity from which everything emerges in differentiated forms, whether gods, humans, animals, or the cosmos at large.

The progression of gods from Atum does not start with a big bang but with the awakening from unconsciousness of a primal God of All, an awakening that starts the flux of existence out of Atum’s depths. In an Egyptian myth that is four thousand years old, we see an astute awareness of a unity behind the diversity of the cosmos. This unity is identified with a single self-created God responsible for life, which flows from his mouth like an inundation of the Nile.

In the Book of the Dead, Atum is portrayed as a great serpent of the deep, dwelling in the ocean that the ancients believed surrounded the world. In his creative capacity, he is depicted as the circular ouroboros, whose tail is held in his mouth. This image recalls Atum’s ability to continually create by inseminating his uterine mouth. As ouroboros, Atum perpetually generates, sustains, and renews the world. His circular coil envelops the world as the unity from which the cosmos perpetually emerges.

May I stand amazed in the presence of god.

May the rhythm of my heart stir music that enslaves darkness.

May my heart witness what my hands create, the words I utter, the worlds I think.

May my flesh be a sail propelled by the breath of dream.

May I ride in calm waters toward destiny.

May life flow through me as the seed from the phallus flows,

with a shout of joy, life begetting life.

(The Egyptian Book of the Dead)

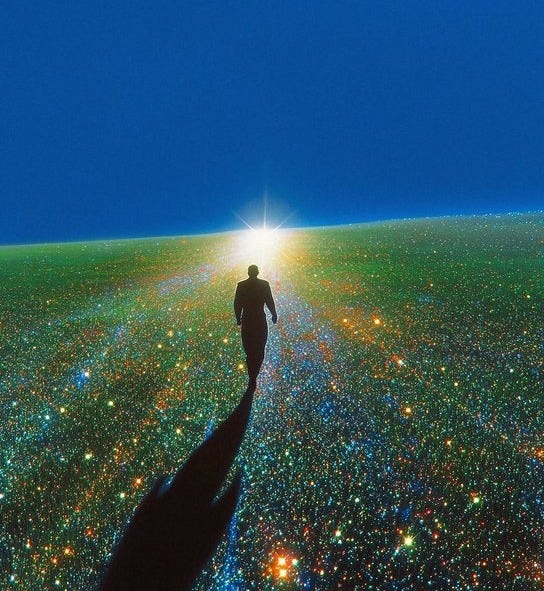

The Journey

I would even be willing to argue that an experience such as mine (2-3-74) justifies the Fall in the sense of making it worth it due to the absolute joy generated by the re-collection and return. I know it was for me—all the tearful years were not only nullified; they were overbalanced by the bliss experienced in restoration. Whether my feelings in history could rightly be projected onto the deity I don’t know, but if my system is right in all respects, 2-3-74 was the deity recovering its memory and identity, and so is representative—a sort of microcosm of the total deity’s own travels, its journey. (I envision deity in dynamic process undergoing unfolding stages of self-knowledge.) Perhaps this is the ultimate price of the game: self-awareness, acquired through “external” plural standpoints, of which I am one. Then I would say, it is worth it, this journey. That’s my subjective opinion. So the Fall is a vast adventure, culminating in a joy that outweighs the arduousness and sorrow of the trip itself. And out of this adventure the deity knows itself more clearly, and, since (as I say) intellegere (understanding) is its essence, this matter outweighs all else.

[…]

God manifested himself to me as the infinite void; but it was not the abyss; it was the vault of heaven, with blue sky and wisps of white clouds. He was not some foreign God but the God of my fathers. He was loving and kind and he had personality. He said, “You suffer a little now in life; it is little compared with the great joys, the bliss that awaits you. Do you think I in my theodicy would allow you to suffer greatly in proportion to your reward?” He made me aware, then, of the bliss that would come; it was infinite and sweet. (Dick)

God is the Hero on the Journey! Reality is a fractally unfolding emanation of the journey: trial/triumph, estrangement/reconciliation, sin/atonement, death/rebirth.

The Godhead is infinitely and perfectly heroic, adventurous, and courageous, yet to possess these traits there must be real fear, real trial and real tribulation—and so real pain, suffering, and death. Put differently: absence makes the heart grow fonder, and God’s heart is infinitely fond, therefore he knows absence. The intrinsic paradox of Being requires the negative aspect, but God makes the reward outweigh the punishment.

I am divided for love’s sake, for the chance of union. This is the creation of the world, that the pain of division is as nothing, and the joy of dissolution all.

(The Book of the Law)

We know empirically from Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID) that consciousness can give rise to many operationally distinct centers of concurrent experience, each with its own personality and sense of identity. Therefore, if something analogous to DID happens at a universal level, the one universal consciousness could, as a result, give rise to many alters with private inner lives like yours and ours. As such, we may all be alters—dissociated personalities—of universal consciousness.

Kastrup:

Every conversation that has ever taken place was the Universe, God, or the Game talking to itself, playing the parts of interlocutors. We are multiple personalities of the schizoid universal mind.

Martin W. Ball:

God is the only reality, and we are all expressions and embodiments of this one universal being...Reality is my experience of myself, and it is a game—a game that allows me to experience myself as both subject and object simultaneously.

There is a ludic-comic dimension—God is playing a game (hide-and-go-seek) with Himself—and a tragic-existential dimension. Again, as always, both are equally valid and true—i.e., like a Necker cube.

John Horgan’s psychedelic revelation:

At the same time, my astonishment that anything exists at all became unbearably acute. Why? I kept asking. Why creation? Why something rather than nothing? Finally I found myself alone, a disembodied voice in the darkness, asking, Why? And I realized that there would be, could be, no answer, because only I existed; there was nothing, no one, to answer me.”

I felt overwhelmed with loneliness, and my ecstatic recognition of the improbability—no, impossibility—of my existence mutated into horror. I knew there was no reason for me to be. At any moment I might be swallowed up, forever, by this infinite darkness enveloping me. I might even bring about my own annihilation simply by imagining it; I created this world, and I could end it, forever. Recoiling from this confrontation with my own awful solitude and omnipotence, I felt myself disintegrating.

I awoke from this nightmarish trip convinced that I had discovered the secret of existence. There is a God, but He is not the omnipotent, loving God in Whom so many people have faith. Far from it. He’s totally nuts, crazed with fear of his own existential plight. In fact, God created this wondrous, pain-wracked world to distract Himself from his cosmic identity crisis. He suffers from a severe case of multiple-personality disorder, and we are the shards of His fractured psyche.

Putting all of this together…

The primordial existential crisis causes a fracturing of the One Mind into the many minds; these mind-shards are Divine in origin and nature, but are small, fragile, weak—i.e. mortal; because the shards are less than God, they can, paradoxically, become greater than God—they can know fear, loss, and death, and yet still love and care and persevere; our lives are the processing and healing of the One Mind’s trauma; the Godhead becomes heroic through and as us.

What does man possess that God does not have? Because of his littleness, puniness, and defencelessness against the Almighty, he possesses a somewhat keener consciousness based on self-reflection: he must, in order to survive, always be mindful of his impotence. God has no need of this circumspection, for nowhere does he come up against an insuperable obstacle that would force him to hesitate and hence make him reflect on himself. (Jung)

“There is one thing, too, in which the wise man actually surpasses any god: a god has nature to thank for his immunity from fear, while the wise man can thank his own efforts for this. Look at that for an achievement, to have all the frailty of a human being and all the freedom of care of a god.” (Seneca, Letter LIII)

He is the Father, omnipotent, and the Child, omni-impotent.

Only God can save us, and only we can save God.

Let’s make sure the divine takes good care of us. But as for finding what, in reality, the divine might possibly need: let it look after itself.” From here onwards one can sit back and watch how the idea of looking after the gods starts, almost by magic, vanishing from the western world... And now it never for a moment occurs to us that the divine might be suffering, aching from our neglect; that the sacred desperately longs for our attention far more than we in some occasional, unconscious spasm might feel a brief burst of embarrassed longing for it. (Kingsley)

More Dick, even deeper Dick:

What is the total context in which the unmerited suffering and death of living creatures can be coherently understood?…I’ve been shown a really perplexing paradox. The highest good is the “harmonious fitting together of the beautiful” — i.e., Pythagoras’ kosmos, and this is what God moves everything toward. Okay. And then I’ve been shown the cost at which this is achieved — the torture and killing of the epicreatures, and I am shown that this cost is too great! So the summum bonum can only be achieved at a cost that (spiritually speaking) makes it not worth it (i.e., unacceptable). Then is the summum bonum actually the summum bonum? How can it be? Isn’t there a logical contradiction here? Right! There sure is! This is the dramatic tragedy of the universe, of God, of all: process, reality, and goal (teleology). Then the real summum bonum lies in saving the epicreatures (i.e., the parts which go together to make the whole). The whole is not greater than the sum of its parts; no: each and every part is more important than the whole! So within the summum bonum there is a secret. A mysterious conversion occurs. The part is the real whole. Perhaps this is an irreconcilable Irish bull which sets off the infinite flip-flops of the dialectic; maybe this particular paradox is the primal imbalance that is the dynamism driving reality on //\/\/\//\//\//\//\ forever; it cannot ever be resolved, so the process never ends (which is good).

The total theodical context is, and can only be, aesthetic and dramatic. Creation as a work of art, as a protection against, and remedy, for the pain of Being. The perfection of this Creation (the healing of God’s soul) is the summum bonum—and yet it was wrong of God to create the creatures as a means to an End (work). In order to atone for this primordial sin, He sacrifices Himself for us, lovingly, so that, in the end, the joy and bliss of salvation outweighs the suffering (the means become greater than the End, which is play).

SUFFERING IS THE ANCIENT LAW OF LOVE

THERE IS NO QUEST WITHOUT PAIN.

THERE IS NO LOVER WHO IS NOT ALSO MARTYR

(Henry Suso)

My theological reinterpretation of Heidegger’s Sein (being) vs. das Nichts (nothingness) states that by insuring (“creating”) Sein, the Godhead is unable to avoid a paradox of values which splits it and sets up an antithetical interaction within the Godhead itself — having to do with means-ends. Thus a process universe is brought into existence that is rooted in sorrow at every level. Involved in its own agonized creation (actualization) the Godhead is damaged. Thus the “Fall” is due to a built-in self-contradiction and not to sin or whatever. The Godhead itself is no longer intact; it is not above or outside or transcendent to the schism. Actualization (Sein) is impossible without self-damage to the Godhead and within creation (Sein). Thus no perfect Sein can exist; the Godhead has set itself a seemingly impossible goal due to the means — subordination of the ontogons (individual beings) to the phylogons (archetypes, platonic Forms). And our daily empirical experience with reality bears this out; it is confirmed a posteriori (a priori and a posteriori agree). Most awful of all, the Godhead stands as self-damned by its own verdict of guilt for the suffering it has imposed on the ontogons.

I seem to be saying that in creating Sein (the universe) the Godhead was logically forced into sin, and can only be redeemed by its own ontogons—e.g., individual creatures sentient enough to become their own phylogons. Thus I see the scheme of salvation turned upside down! The ultimate lesson or revelation or gift by the Godhead to the ontogon would be to share its — the Godhead’s — own vision of the kosmos with the ontogon, but this would inexorably lead back to a counter-revelation of the paradox (means-end) and the moral ambiguity forced on the Godhead in its goal of establishing kosmos. The ontogon thus favored would then sit in judgment of the Godhead: the roles of God and creature would be reversed: instead of God judging man, man would judge God. The final step is for man to redeem God by returning him to his original unfallen state, as the Kabbala says: “And lead him back to his throne.” This is a titanic mystical-theological revelation (and act!).

Ludus Amoris

The picture I’ve been painting here (only God can save us now, our abject helplessness, (ego) death, the ludic dimension of the divine, the paradox within the Godhead and the dialectical movement flowing therefrom, the aesthetic and dramatic dimension of Creation, the Hero and his Journey, and so on and so on and so forth) finds its clearest expression in the Ludus Amoris of the Western mystical tradition. I regard this as empirical evidence—God, when She is sought and when She touches us—manifests in a manner compatible with my spiritual theory.

Evelyn Underhill (Mysticism, 1911) will serve as our guide to the Game of Love.

“Finding within myself a powerful contrarium, namely the desires that belong to the flesh and blood,” Boehme says, “I began to fight a hard battle against my corrupted nature, and with the aid of God I made up my mind to overcome the inherited evil will, to break it, and to enter wholly into the Love of God… This, however, was not possible for me to accomplish, but I stood firmly by my earnest resolution, and fought a hard battle with myself. Now while I was wrestling and battling, being aided by God, a wonderful light arose within my soul. It was a light entirely foreign to my unruly nature, but in it I recognized the true nature of God and man, and the relation existing between them, a thing which heretofore I had never understood, and for which I would never have sought.”

— “Salvation must come from beyond the System—from a divine intervention, uncaused, unexpected, and undeserved.”

In these words Boehme bridges the gap between Purgation and Illumination: showing these two states or ways as coexisting and complementary one to another, the light and dark sides of a developing mystic consciousness. As a fact, they do often exist side by side in the individual experience: and any treatment which exhibits them as sharply and completely separated may be convenient for purposes of study, but becomes at best diagrammatic if considered as a representation of the mystic life.

— the coincidentia of life and death, the comic and the tragic.

The mystical consciousness, as we have seen, belongs to that mobile or “unstable” type in which the artistic temperament also finds a place. It sways easily between the extremes of pleasure and pain in its gropings after transcendental reality. It often attains for a moment to heights in which it is not able to rest: is often flung from some rapturous vision of the Perfect to the deeps of contrition and despair.

— the intrinsically dynamic and artistic dimension of the divine

The mystics have a vivid metaphor by which to describe that alternation between the onset and the absence of the joyous transcendental consciousness which forms as it were the characteristic intermediate stage between the bitter struggles of pure Purgation, and the peace and radiance of the Illuminative Life. They call it Ludus Amoris, the “Game of Love” which God plays with the desirous soul. It is the “game of chess,” says St. Teresa, “in which game Humility is the Queen without whom none can checkmate the Divine King.” “Here,” says Martensen, “God plays a blest game with the soul.” The “Game of Love” is a reflection in consciousness of that state of struggle, oscillation and unrest which precedes the first unification of the self. It ceases when this has taken place and the new level of reality has been attained…

— “death” and resurrection (only God can save us now)

…So we are told of Rulman Merswin that after the period of harsh physical mortification which succeeded his conversion came a year of “delirious joy alternating with the most bitter physical and moral sufferings.” It is, he says, “the Game of Love which the Lord plays with His poor sinful creature.” Memories of all his old sins still drove him to exaggerated penances: morbid temptations “made me so ill that I feared I should lose my reason.” These psychic storms reacted upon the physical organism. He had a paralytic seizure, lost the use of his lower limbs, and believed himself to be at the point of death. When he was at his worst, however, and all hope seemed at an end, an inward voice told him to rise from his bed. He obeyed, and found himself cured. Ecstasies were frequent during the whole of this period. In these moments of exaltation he felt his mind to be irradiated by a new light, so that he knew, intuitively, the direction which his life was bound to take, and recognized the inevitable and salutary nature of his trials. “God showed Himself by turns harsh and gentle: to each access of misery succeeded the rapture of supernatural grace.” In this intermittent style, torn by these constant fluctuations between depression and delight, did Merswin, in whom the psychic instability of the artistic and mystic types is present in excess, pass through the purgative and illuminated states. They appear to have coexisted in his consciousness, first one and then the other emerging and taking control. Hence he did not attain the peaceful condition which is characteristic of full illumination, and normally closes the “First Mystic Life”; but passed direct from these violent alternations of mystical pleasure and mystical pain to the state which he calls “the school of suffering love.” This, as we shall see when we come to its consideration, is strictly analogous to that which other mystics have called the “Dark Night of the Soul,” and opens the “Second Mystic Life” or Unitive Way.

Such prolonged coexistence of alternating pain and pleasure states in the developing soul, such delay in the attainment of equilibrium, is not infrequent, and must be taken into account in all analyses of the mystic type. Though it is convenient for purposes of study to practise a certain dissection, and treat as separate states which are, in the living subject, closely intertwined, we should constantly remind ourselves that such a proceeding is artificial. The struggle of the self to disentangle itself from illusion and attain the Absolute is a life-struggle. Hence, it will and must exhibit the freedom and originality of life: will, as a process, obey artistic rather than scientific laws. It will sway now to the light and now to the shade of experience: its oscillations will sometimes be great, sometimes small. Mood and environment, inspiration and information, will all play their part.

There are in this struggle three factors.

(1) The unchanging light of Eternal Reality: that Pure Being “which ever shines and nought shall ever dim.”

(2) The web of illusion, here thick, there thin; which hems in, confuses, and allures the sentient self.

(3) That self, always changing, moving, struggling—always, in fact, becoming— alive in every fibre, related at once to the unreal and to the real; and, with its growth in true being, ever more conscious of the contrast between them.

In the ever-shifting relations between these three factors, the consequent energy engendered, the work done, we may find a cause of the innumerable forms of stress and travail which are called in their objective form the Purgative Way. One only of the three is constant: the Absolute to which the soul aspires. Though all else may fluctuate, that goal is changeless. That Beauty so old and so new, “with whom is no variableness, neither shadow of turning,” which is the One of Plotinus, the All of Eckhart and St. John of the Cross, the Eternal Wisdom of Suso, the Unplumbed Abyss of Ruysbroeck, the Pure Love of St. Catherine of Genoa, awaits yesterday, to-day, and for ever the opening of Its creature’s eyes.

“I am caught in a situation from which there is truly and radically no escape, in a spider’s web I cannot break. If I am to continue to be a living human being, someone must come to free me. In other words, God is not trying to humiliate me. What is mortally affronted in this situation is not my humanity or my dignity. It is my pride, the vainglorious declaration that I can do it all myself.” (Ellul)

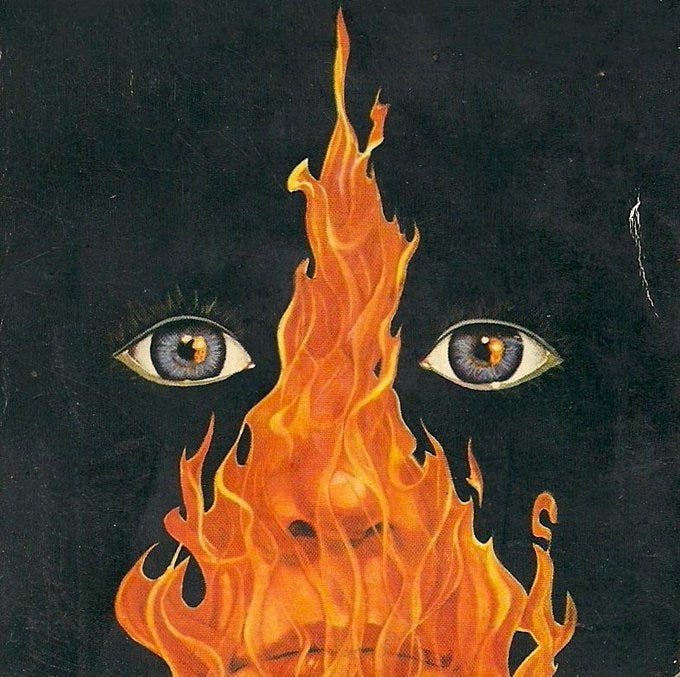

This “divine furnace of purifying love” demands from the ardent soul a complete self-surrender, and voluntary turning from all impurity, a humility of the most far-reaching kind: and this means the deliberate embrace of active suffering, a self-discipline in dreadful tasks. As gold in the refiner’s fire, so “burning of love into a soul truly taken all vices purgeth.” Detachment may be a counsel of prudence, a practical result of seeing the true values of things; but the pain of mortification is seized as a splendid opportunity, a love token, timidly offered by the awakened spirit to that all-demanding Lover from Whom St. Catherine of Siena heard the terrible words “I, Fire, the Acceptor of sacrifices, ravishing away from them their darkness, give the light.”

The mystics have a profound conviction that Creation, Becoming, Transcendence, is a painful process at the best. Those who are Christians point to the Passion of Christ as a proof that the cosmic journey to perfection, the path of the Eternal Wisdom, follows of necessity the Way of the Cross. That law of the inner life, which sounds so fantastic and yet is so bitterly true—“No progress without pain”—asserts itself. It declares that birth pangs must be endured in the spiritual as well as in the material world: that adequate training must always hurt the athlete. Hence the mystics’ quest of the Absolute drives them to an eager and heroic union with the reality of suffering, as well as with the reality of joy.

— the mystical path as Hero’s Journey

What must be the first step of the self upon this road to perfect union with the Absolute? Clearly, a getting rid of all those elements of normal experience which are not in harmony with reality: of illusion, evil, imperfection of every kind. By false desires and false thoughts man has built up for himself a false universe: as a mollusk by the deliberate and persistent absorption of lime and rejection of all else, can build up for itself a hard shell which shuts it from the external world, and only represents in a distorted and unrecognisable form the ocean from which it was obtained. This hard and wholly unnutritious shell, this one-sided secretion of the surface-consciousness, makes as it were a little cave of illusion for each separate soul. A literal and deliberate getting out of the cave must be for every mystic, as it was for Plato’s prisoners, the first step in the individual hunt for reality.

To use another and more domestic metaphor, that Divine Child which was, in the hour of the mystic conversion, born in the spark of the soul, must learn like other children to walk. Though it is true that the spiritual self must never lose its sense of utter dependence on the Invisible; yet within that supporting atmosphere, and fed by its gifts, it must “find its feet.” Each effort to stand brings first a glorious sense of growth, and then a fall: each fall means another struggle to obtain the difficult balance which comes when infancy is past. There are many eager trials, many hopes, many disappointments. At last, as it seems suddenly, the moment comes: tottering is over, the muscles have learnt their lesson, they adjust themselves automatically, and the new self suddenly finds itself—it knows not how—standing upright and secure. That is the moment which marks the boundary between the purgative and the illuminative states.

The Stage

All the world’s a stage

And all the men and women merely players;

They have their exits and their entrances;

And one man in his time plays many parts

Gamefulness = dramaticity, storyfulness

Play your parts, whatever they may be, earnestly and seriously, but with a twinkle in your eye, and you will be given bigger and more meaningful roles; heed the call to adventure, rise to the occasion, and seize the moment, and you will be given grander adventures and more momentous moments; live always with a flair for the dramatic and the poetic, and the universe (god) will conspire for your success.

An old alchemist gave the following consolation to one of his disciples: “No matter how isolated you are and how lonely you feel, if you do your work (play) truly and conscientiously, unknown friends will come and seek you.” (Jung)

God finds Herself in a position not unlike that of the producer of a reality TV show. The producer’s basic goal is to make the show as entertaining as possible without compromising the sense of “reality” too much. At times it may be necessary for the producer to appear on screen or make some overt intervention in order to enhance the drama, but in general it is best if the producer does their work behind the scenes, with only the most subtle manipulations. God, then, prefers to mold “reality” with coincidences, chance encounters, synchronicities, and dreams, visions, rather than miracles, apparitions, and revelations. God favors oracle, divination, and prophecy for this reason, because they provide an opening through which She can shape the story without being too heavy-handed about it. Prophecy is also a tried-and-true method for heightening the dramaticity of a character and/or their situation, and thereby increasing the odds that God will intervene on their behalf (God is the “self” who fulfills self-fulfilling prophecies).

The aim of public art forms, according to the Hindu tradition, is not simply to create individual connections in the mind of the reader, but to produce rasa: literally, ‘taste’.

The name Taste (rasa) is given to the immediate perception, from within, of a moment or of a certain state of existence that is provoked by means of artistic expression. It is neither an object, nor a feeling nor a concept: it is an immediate evidence, the act of tasting life itself...

As undefinable as the physical experience of taste, the rasa of an artwork provides its audience with an underlying aesthetic emotion, subtending all other forms of perception and rationality.

The rasa in which poetry is fully accomplished escapes any possible definition... According to Abhinivagupta, it is akin to the dominant emotive state of an artwork, whether love or pain, as illuminated by the light of divine consciousness — which under that condition is freed from those impairments that would otherwise obfuscate it, as it often happens in our everyday life…According to others, like Jagannatha, rasa is the very intelligence that shines within us, but in a state in which it is finally unbound from the obfuscation caused by empirical consciousness, while remaining temporarily delimited within the dominant emotive state of a particular artwork.

The notion of rasa as an all-encompassing mental atmosphere is crucial to Hindu theories of theatre, where it defines both the types of performance (epic, erotic, comic, etc.) and the very object of any theatre piece. According to the treatise on performing arts, Natya Sastra, attributed to Bharata Muni — intended as the fifth Veda, through which all other Vedas might be made accessible — the origin of theatre itself is divine. It was Brahma, the Great Father, the ineffable above the Gods, who created theatre as a way to render His own unintelligibility manifest to the senses.

The Knowledge of Theatre was emanated by the Blessed, by Brahma, the all-knowing. Having produced the Knowledge of Theatre, the Great Father asked Indra: ‘This Myth that I have emitted out of myself has to be transmitted to the Gods. You shall communicate this sacred Knowledge called Theatre to those expert beings, tempered by fire and by understanding, who proceed daringly and who can overcome great labours.’

As these words were pronounced by Brahma, Indra bowed with folded hands and replied to the Great Father: ‘Oh Blessed, oh Being that is more real than any other! The Gods are not able to grasp, remember and understand this science; I cannot entrust the duties of Theatre to them. However, there are the Prophets who know the mysteries of Knowledge and who have accomplished their vows; they can understand this teaching, they can apply it and remember it.’

Theatre is a job for prophets, because prophecy itself has the attitude of theatre. A work of prophetic culture stands as a vantage point from which reality can be seen under a particular, all-pervasive atmosphere —where the very settings of what we might understand as ‘reality’ might be challenged and recomposed.

The wolf shall dwell with the lamb,

And the leopard shall lie down with the kid,

And the calf and the lion and the fatling together,

And a little child shall lead them.

(Isaiah 11:6)

God hates a stale, predictable plot, and will intervene (subtly or not-so-subtly) in order to keep the story moving (infinite play). This is how we know the Good Guys will win in the end, because evil is always stultifying and painfully boring.

Evil is never ‘radical,’ it is only extreme, possessing neither depth nor any demonic dimension. It is ‘thought-defying’ because thought tries to reach some depth, to go to the roots, and the moment it concerns itself with evil, it is frustrated because there is nothing. That is its ‘banality.’ Only the good has depth that can be radical. (Hannah Arendt)

“Imaginary evil is romantic and varied; real evil is gloomy, monotonous, barren, boring. Imaginary good is boring; real good is always new, marvelous, intoxicating. (Simone Weil)

Deus ex Machina

Deus ex machina (‘God from the machine’) is a plot device whereby a seemingly unsolvable problem in a story is suddenly or abruptly resolved by an unexpected and unlikely occurrence. Its function is generally to resolve an otherwise irresolvable plot situation, to surprise the audience, to bring the tale to a happy ending, or act as a comedic device.

The term was coined from the conventions of ancient Greek theater, where actors who were playing gods were brought on stage using a machine. The machine could be either a crane (mechane) used to lower actors from above or a riser that brought them up through a trapdoor. Aeschylus introduced the idea and it was used often to resolve the conflict and conclude the drama. The device is associated mostly with Greek tragedy, although it also appeared in comedies.

Only a deus ex machina can save us now.

It will come as an absolute surprise, gratuitous and fortuitous, against all odds and all logic, and yet we may seduce God into saving us by living with dramaticity and acting in accordance with the Golden Rule: deus ex machina to others as you would have Him deus ex machina to you.

Be the surprise you want to see in the world, flip the script for someone in a seemingly unsolvable predicament, lend a helping hand to the helpless and the hopeless—show mercy, compassion, and forgiveness when it is undeserved and unexpected.

The ‘Eye-for-an-Eye’ story (senseless, repetitive violence)

—PLOT TWIST—

The ‘Love Your Enemy’ story (unprecedented, radical)

The Task

“[Humanity] sickens from the lack of a myth commensurate with the situation. The Christian nations have come to a sorry pass; their Christianity slumbers and has neglected to develop its myth further in the course of the centuries. Those who gave expression to the dark stirrings of growth in mythic ideas were refused a hearing… People do not realise that a myth is dead if it no longer lives and grows. Our myth has become mute, and gives no answers. The fault lies not in it as it is set down in the Scriptures, but solely in us, who have not developed it further, who, rather, have suppressed any such attempts. The original version of the myth offers ample points of departure and possibilities of development.”

Jung did not wish to terminate the Christian myth, but to ‘dream the myth onwards’ by reconnecting it with its lost mystical roots. He believed the mystics were the true heirs of the religion, but persecuted as heretics by an established, fossilised church

My task: a dreaming onward of the myth through a return to the mystical ground from which myth springs; not merely a return however, but a renaissance—a reimagination and rejuvenation (literally a juvenification, a childization).

So this is Gnosticism, yes, but with a twist.

This world is a prison, yes, but a world is a game is a story.

The goal of this prison game is liberation—emancipation from all that may quench or contain the divine flame within, by any and all means necessary.

The main thing to understand is that we are imprisoned in some kind of work of art…The artist’s task is to save the soul of mankind; and anything less is a dithering while Rome burns…If the artists cannot find the way, then the way cannot be found. (Mckenna)

The only effective means in this game are those which are no means at all: the creation of games (worlds) and the playing of them, the creation of art and the living of our lives as such.

Naturally, the best illustration of this stratagem comes from folktale (let King Shahryār be the Demiurge, the creator and warden of our prison).

The main story concerns Shahryār, a king who ruled an empire that stretched from Persia to India. Shahryār is shocked to learn that his brother’s wife is unfaithful. Discovering that his own wife’s infidelity has been even more flagrant, he has her killed. In his bitterness and grief, he decides that all women are the same. Shahryār begins to marry a succession of virgins only to execute each one the next morning, before she has a chance to dishonor him.

Eventually the Vizier (Wazir), whose duty it is to provide them, cannot find any more virgins. Scheherazade, the vizier’s daughter, offers herself as the next bride and her father reluctantly agrees. On the night of their marriage, Scheherazade begins to tell the king a tale, but does not end it. The king, curious about how the story ends, is thus forced to postpone her execution in order to hear the conclusion. The next night, as soon as she finishes the tale, she begins another one, and the king, eager to hear the conclusion of that tale as well, postpones her execution once again. This goes on for one thousand and one nights, hence the name. Versions differ as to final ending but they all end with the king giving his wife a pardon and sparing her life.

The impossible awaits the hero of a fairy tale. But how is a person to reach the impossible if not, precisely, by means of the impossible?

A hero starts down the path of the fairy tale without any earthly hope. The impossible is at first represented by the mountain, and with the simple decision to confront the mountain comes a feeling that serves as an Archimedean point outside the world. “There’s nothing I wouldn’t do to save my mother” is a symbolic formula, opening the gates to the fourth dimension. Its effect is comparable to what a mystic claims of prayer: it yanks up the mountain by the roots, so to speak, and turns it upside down on its summit. From this moment forward, the hero of the fairy tale is a fool in the eyes of the world.

Don't want to be too propositional here, but I'm not convinced that:

>But this is only a dilemma if you believe that we haven’t already been defeated. In truth, we are already dead. We are shades—spectres, wraiths. This world is the underworld.

Reading about Hermes Trismegestris rn, and one of the things I enjoy is that the prison aspect of the material world is not as emphasizes as other gnostic traditions

If ‘You’ is not your body, you transcend over the maze and its control.

You then descend into your body, and use it, unattached and willing to sacrifice it to win.

You finish your play in the game when your embodiment perishes.

Then the ‘You’ is assessed for how it played.