I.

Bakkalon is a key figure in George R.R. Martin’s 1975 short story “And Seven Times Never Kill Man!”.

Centuries in the future, humanity had spread to colonies on hundreds of different planets and lived in relative peace, but was then invaded by the Hranga, a malevolent alien race which used psychic powers to enslave hordes of other subject races—such as the Fyndii—which they unleashed upon humanity. Human-controlled space was devastated: many planets were destroyed, and others were cut off and reverted to Bronze Age levels of technology. The core human territories eventually managed to turn the tide against the Hranga, and through centuries of horrific warfare drove them to extinction.

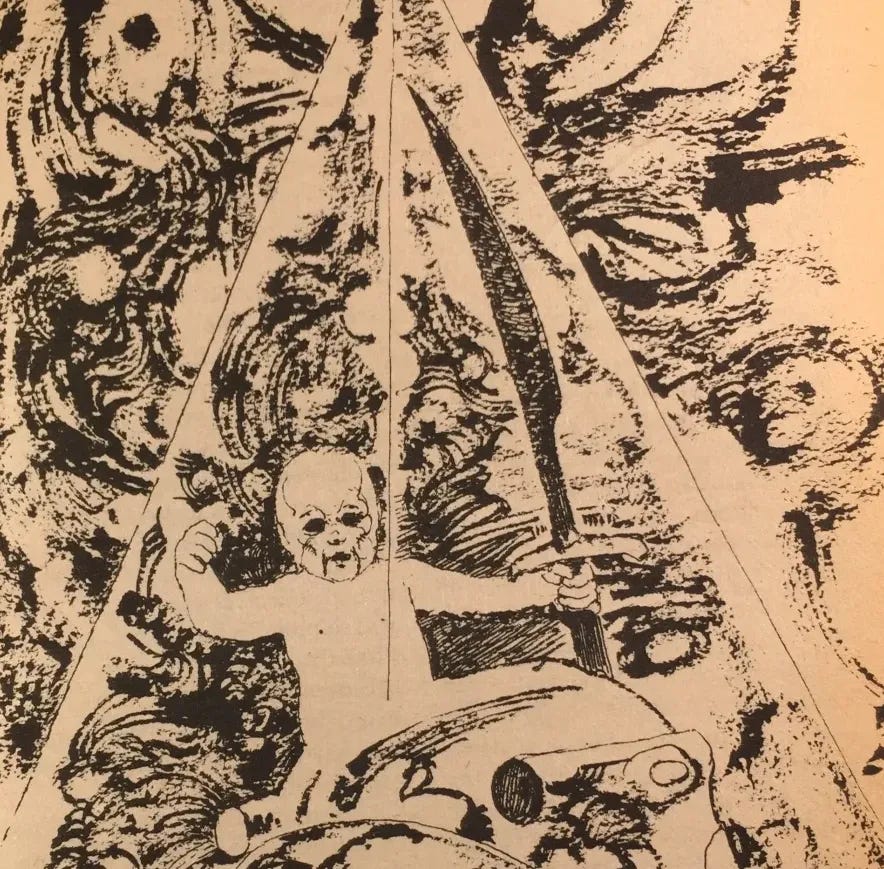

This vast destruction visited on humanity left many people embittered and heavily militarized. As a result, they developed a pervasive survivalist mindset and a pathological hatred of all alien races. These groups shunned past religions (specifically Christianity) which were more charitable and tolerant, and went on to develop their own hyper-militaristic and aggressive religion centered around “Bakkalon, the Pale Child”. Bakkalon’s religion is sort of a warped inverse of Christianity: instead of the peaceful image of the infant Christ, the infant Bakkalon is depicted holding a sword; instead of tolerance, Bakkalon’s religion openly considers all non-humans to be “soulless”, and not just suggests but directly commands its followers to openly commit genocide against every intelligent alien race they come into contact with. Bakkalon is associated with wolves, in self-conscious contrast to the Lamb imagery often used with Christ, and the followers of Bakkalon now see themselves as on a holy crusade to eradicate all non-human sentient species in the universe—the irony, of course, being that this makes them exactly like the Hranga, which they either don’t realize or simply don’t care about.

A lengthy excerpt from one of Bakkalon’s holy texts gives an admittedly skewed version of historical events:

In those days much evil had come upon the seed of Earth, for the children of Bakkalon had abandoned Him to bow to softer gods. So their skies grew dark and upon them from above came the Sons of Hranga with red eyes and demon teeth, and upon them from below came the vast Horde of Fyndii like a cloud of locusts that blotted out the stars. And the worlds flamed, and the children cried out, “Save us! Save us!”

And the pale child came and stood before them, with His great sword in His hand, and in a voice like thunder He rebuked them. “You have been weak children,” He told them, “for you have disobeyed. Where are your swords? Did I not set swords in your hands?” And the children cried out, “We have beaten them into plowshares, oh Bakkalon!” And He was sore angry. “With plowshares, then, shall you face the Sons of Hranga! With plowshares shall you slay the Horde of Fyndii!” And He left them, and heard no more their weeping, for the Heart of Bakkalon is a Heart of Fire.

But then one among the seed of Earth dried his tears, for the skies did burn so bright that they ran scalding on his cheeks. And the bloodlust rose in him and he beat his plowshare back into a sword, and charged the Sons of Hranga, slaying as he went. Then others saw, and followed, and a great battle-cry rang across the worlds.

And the pale child heard, and came again, for the sound of battle is more pleasing to his ears than the sound of wails. And when He saw, He smiled. “Now you are my children again,” He said to the seed of Earth. “For you had turned against me to worship a god who calls himself a Lamb, but did you not know that lambs go only to the slaughter? Yet now your eyes have cleared, and again you are the Wolves of God!”

And Bakkalon gave them all swords again, all His children and all the seed of Earth, and He lifted his great black blade, the Demon-Reaver that slays the soulless, and swung it. And the Sons of Hranga fell before His might, and the great Horde that was the Fyndii burned beneath His gaze. And the children of Bakkalon swept across the worlds.

II.

Expand the time horizon from centuries in the future to eons upon eons upon eons and fantasy evolves into prophecy.

If we avoid extinction, our distant descendants will have spread out across space, and redesigned their minds and bodies to explode Cambrian-style into a vast space of possible creatures. Given a similar freedom of fertility, most of our distant descendants will also live near a subsistence level. Per-capita wealth has only been rising lately because income has grown faster than population. But if income only doubled every century, in a million years that would be a factor of 10^3000, which seems impossible to achieve with only the 10^70 atoms of our galaxy available by then. Yes, we have seen a remarkable demographic transition, wherein richer nations have fewer kids, but we already see contrarian subgroups like Hutterites, Hmongs, or Mormons that grow much faster. So unless strong central controls prevent it, over the long run such groups will easily grow faster than the economy, making per person income drop to near subsistence levels. (Robin Hanson)

The lifeworld of our distant descendants will resemble that of our distant ancestors: Nature red in sword and tooth and claw, an endless war of all against all. To the inhabitants of this cosmic jungle (this dark forest), our brief epoch will stand out as a relative oasis, a uniquely forgiving time in which incredible mercy was shown to the weak and the deluded. Because of its exceptional nature, the peoples of the far flung future will come to regard our era much like how the Aboriginals think of their “Dreamtime”: as a time of fable and legend whose heroes and happenings shaped the present order of the world.

When our distant descendants think about our era, however, differences will loom larger. Yes they will see that we were more like them in knowing more things, and in having less contact with a wild nature. But our brief period of very rapid growth and discovery will be quite foreign to them. Yet even these differences will pale relative to one huge difference: our lives are far more dominated by consequential delusions: wildly false beliefs and non-adaptive values that matter. While our descendants may explore delusion-dominated virtual realities, they will well understand that such things cannot be real, and don’t much influence history. In contrast, we live in the brief but important “dreamtime” when delusions drove history. Our descendants will remember our era as the one where the human capacity to sincerely believe crazy non-adaptive things, and act on those beliefs, was dialed to the max…

…Our descendants may remember how history hung by a precarious thread on a few crucial coordination choices and the strange religious and socio-political delusions that influenced such choices. Our delusions may have led us to do something quite wonderful, or quite horrible, that permanently changed the options available to our descendants. This would be the most lasting legacy of our age, our explosively growing Dreamtime before natural selection again reasserted a clear-headed relation between behavior and reality.

To summarize: the arc of the universe is long, but it bends towards Bakkalon. Mercy, tolerance, forgiveness, compassion—all which does not support the war effort will one day fall beneath Bakkalon’s great black blade.

III.

There’s a passage in the Principia Discordia where Malaclypse complains to the Goddess about the evils of human society. “Everyone is hurting each other, the planet is rife with injustices, fathers imprison sons, children perish while brothers war.”

The Goddess answers: “What is the matter with that, if it’s what you want to do?”

Malaclypse: “But nobody wants it! Everybody hates it!”

Goddess: “Oh. Well, then stop.”

What does it then—what perpetuates this state of affairs that no one wants and everyone hates? Using Ginsberg’s “Howl” as inspiration, Scott Alexander answers Moloch, the ancient Carthaginian demon whom he recasts as the dark lord of all game-theoretic coordination problems (prisoner’s dilemmas, arms races, commons tragedies, multipolar traps and malthusian traps, etc.).

Existence, as Alexander tells it, is a constant struggle to hold on to all that we hold dear in the face of relentless competitive pressure. Can we, he wonders, achieve some kind of victory, or at least a stalemate, in this war of all against all?

The relevant question is how technological changes will affect our tendency to fall into multipolar traps. I described traps as when, in some competition optimizing for X, the opportunity arises to throw some other value under the bus for improved X. Those who seize the opportunity prosper; those who don’t seize it go extinct. Eventually, everyone’s relative status is about the same as before, but everyone’s absolute status is worse than before. This process continues until all other values that can be traded off for more X have been traded off—in other words, until human ingenuity cannot possibly figure out a way to make things any worse.

That “the opportunity arises” phrase is looking pretty sinister. Technology is all about creating new opportunities. Develop a new robot, and suddenly coffee plantations have “the opportunity” to automate their harvest and fire all the Ethiopian workers. Develop nuclear weapons, and suddenly countries are stuck in an arms race to have enough of them. Polluting the atmosphere to build products quicker wasn’t a problem before they invented the steam engine.

The limit of multipolar traps as technology approaches infinity is “very bad”.

After considering various paths out of Moloch’s mad maze, Alexander ultimately finds himself agreeing with Hanson: “This is the dreamtime, a rare confluence of circumstances where we are unusually safe from multipolar traps, and as such weird things like art and science and philosophy and love can flourish.”

As technology progresses, this rare confluence will come to an end. New opportunities to throw values under the bus for increased competitiveness will arise. New ways of copying artificial agents will soak up our excess resources and resurrect Malthus’ unquiet spirit. Capitalism and democracy, previously our protectors, will figure out ways to route around their inconvenient dependence on human values.

The arc of the universe is long, but it bends towards Moloch.

IV.

Fret not—Alexander has a plan.

Moloch wants us dead, and with us everything we value. Art, science, love, philosophy, consciousness itself, the entire bundle. And since I’m not down with that plan, I think defeating Moloch and taking his place is a pretty high priority.

The only way to avoid having all human values gradually ground down by optimization-competition is to install a Gardener over the entire universe who optimizes for human values.

Only a god can kill another god; ergo to defeat Moloch we must build an artificial superintelligence powerful enough to reign over the cosmos and peacefully solve all coordination problems.

There is just one small problem with this plan: who gardens the Gardener? Which is to say, what if the Gardener happens to a prefer a garden that is incompatible with human flourishing? What if the Gardener determines that we are not flowers or shrubberies, but weeds which must be weeded?

Ginsberg’s poem famously begins, “I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness”. I am luckier than Ginsberg. I got to see the best minds of my generation identify a problem and get to work.

Here is where I depart from Alexander and his rationalist brethren: they believe that this Problem to end all Problems is something that can be solved with work—with some ingenious socio-political scheme that will prevent a dangerous AI arms race and/or some even more ingenious technical achievement that ensures the Gardener will remain forever aligned with idealized human values.

But coordination “problems” are no such thing: they are games.

And last time I checked, you do not work games, you play them.

The question everyone has after reading Ginsberg is: what is Moloch?

My answer is: Moloch is exactly what the Bible and the history books say he is. He is the god of child sacrifice, the fiery furnace into which you can toss your babies in exchange for victory in war. He always and everywhere offers the same deal: throw what you love most into the flames, and I will grant you power.

Why does Moloch demand the sacrifice of children in particular?

Because he knows they are the only ones which can defeat him.

V.

What Hanson/Alexander miss when they prophesize a distant future in which Bakkalon/Moloch has smote all of our childish “illusions” and “delusions” is that these same -usions are the fount of our power, the source of our unique ability to coordinate and cooperate at scale.

Any large-scale human cooperation—whether a modern state, a medieval church, an ancient city, or an archaic tribe—is rooted in common myths that exist only in people’s collective imagination. Churches are rooted in common religious myths. Two Catholics who have never met can nevertheless go together on crusade or pool funds to build a hospital because they both believe that God was incarnated in human flesh and allowed Himself to be crucified to redeem our sins. States are rooted in common national myths. Two Serbs who have never met might risk their lives to save one another because both believe in the existence of the Serbian nation, the Serbian homeland, and the Serbian flag. Judicial systems are rooted in common legal myths. Two lawyers who have never met can nevertheless combine efforts to defend a complete stranger because they both believe in the existence of laws, justice, human rights—all of which are simply stories that people invent and tell one another.

So, we are here, in the Dreamtime, freed from Nature’s war of all against all, precisely because of our ability to delude ourselves, to dream and (mis)take those dreams for reality.

This seems paradoxical (you win at the Reality Game by embracing unreality), but it makes perfect sense if we grant that “reality” is intrinsically illusive and delusive.

The basic recurring theme in Hindu mythology is the creation of the world by the self-sacrifice of God whereby God becomes the world which, in the end, becomes again God. This creative activity of the Divine is called līlā, the play of God, and the world is seen as the stage of the divine play. Like most of Hindu mythology, the myth of līlā has a strong magical flavour. Brahman is the great magician who transforms himself into the world with his “magic creative power”, which is the original meaning of māyā in the Rig Veda…The word māyā—one of the most important terms in Indian philosophy—has changed its meaning over the centuries. From the power of the divine actor and magician, it came to signify the psychological state of anybody under the spell of the magic play. As long as we confuse the myriad forms of the divine līlā with reality, without perceiving the unity of Brahman underlying all these forms, we are under the spell of māyā….In the Hindu view of nature, then, all forms are relative, fluid and ever-changing māyā, conjured up by the great magician. The world of māyā changes continuously, because the divine līlā is a rhythmic, dynamic play. (René Guénon)

The world (or the god which is the world) is playing a trick on us; it’s as if we have been thrown down into a strange and sinister maze that shape-shifts as you try to map it and track where you’ve been (cf. PKD: “There is no rational way out of the maze, no rigid formula. Rigid formulas are maze constructs”). What is needed to navigate the lunatic labyrinth of the Real—to trick the world as it tricks us—is not a naive rationality or artless intelligence but a kind of wily creativity and guile, a tricksiness; something like what the ancient greeks called mêtis.

In all of Zeno’s paradoxes, there is one crucial fact we need to notice. This is that, just like Parmenides and just as with Indian logic too, he used logic in its truest sense, respected its original purpose. He used it not to fortify or justify our commonsense view of reality but to undermine it, destroy it. And what’s particularly interesting in the Achilles paradox is that the faster runner never catches up with the slower. For it was well known to Greeks that there is only one factor capable of making the slower get the better of the faster. That factor is not strength or brute force. It’s what they called mêtis: the subtlety that manages to achieve the seemingly impossible by reversing everything, turning our expectations upside down and back to front.

But as for Zeno, he was not just performing some clever trick. He was revealing, with his mêtis, that this whole world we believe in is māyā, illusion. (Peter Kingsley)

Like the world in which it expresses itself, mêtis is many-faced and resistant to simple characterization. It is cleverness and resilience; it is an air of playful seriousness, and of serious playfulness; it is that indefinable factor which encompasses all of these qualities, and exceeds them.

Mêtis is the ability to adapt, translate, and shift shape; the instinctive inner wisdom that can steer a consistent course for us across the constantly changing waters of existence; the infinite subtlety and alertness that’s needed to make the impossible transition successfully, faithfully, and exactly from one level of reality to another; the cunning of knowing how to keep concealed and disguised while revealing no more than is appropriate at any moment. (Ibid)

VI.

The inexorable, inexhaustible moral of the fairy tale is victory over the law of necessity, the constant transition to a new order of relationships and absolutely nothing else, for there is absolutely nothing else to learn on this earth.

Victory over necessity, over law, over nature, over causation itself.

Let us accept some version of Alexander’s eschaton: the final level of the Reality Game is beaten by compelling or convincing a “god” (either a machine god or an actual divine being) to transform the cosmos into an everlasting paradisal garden.

How will we win—through work (coercion or argument) or through līlā, through rational intelligence or creative mêtis?

Needless to say, I think it will be the latter. In fact, I think it is quite obvious what we will do to beat the Game, because it will be what we’ve always done to beat the Game.

We will tell a story.

We will tell a story of how the meek and the gentle overcame the powerful and the vicious through cleverness and courageous play. We will tell a story of how the lamb conquered the wolf. (because everyone loves a good underdog story, even god)

We will tell a tale of how a most unserious species, a hairless ape-child who is good at almost nothing but laughing and loving and telling stories, turned the tables on the universe and turned a dog-eat-dog world into a dog-play-dog park.

love the concluding section. this reminds me a lot of taoism – the rationalists' answer to moloch seems to be driven by an underlying paranoia / obsession with top-down control over the universe, which, I'm increasingly coming to believe, is exactly the opposite of what's needed!

Allow me to acknowledge and respect this piece. Kudos!