Living and Dying with a Mad God

Science, Revelation, Philosophy

I.

“In 2015, doctors in Germany reported the extraordinary case of a woman who suffered from what has traditionally been called “multiple personality disorder” and today is known as “dissociative identity disorder” (DID). The woman exhibited a variety of dissociated personalities (“alters”), some of which claimed to be blind. Using EEGs, the doctors were able to ascertain that the brain activity normally associated with sight wasn’t present while a blind alter was in control of the woman’s body, even though her eyes were open. Remarkably, when a sighted alter assumed control, the usual brain activity returned.

This was a compelling demonstration of the literally blinding power of extreme forms of dissociation, a condition in which the psyche gives rise to multiple, operationally separate centers of consciousness, each with its own private inner life.”

“To circumvent the hard problem of consciousness, some philosophers have proposed an alternative: that experience is inherent to every fundamental physical entity in nature. Under this view, called “constitutive panpsychism,” matter already has experience from the get-go, not just when it arranges itself in the form of brains. Even subatomic particles possess some very simple form of consciousness. Our own human consciousness is then (allegedly) constituted by a combination of the subjective inner lives of the countless physical particles that make up our nervous system.

However, constitutive panpsychism has a critical problem of its own: there is arguably no coherent, non-magical way in which lower-level subjective points of view—such as those of subatomic particles or neurons in the brain, if they have these points of view—could combine to form higher-level subjective points of view, such as yours and ours. This is called the combination problem and it appears just as insoluble as the hard problem of consciousness.

The obvious way around the combination problem is to posit that, although consciousness is indeed fundamental in nature, it isn’t fragmented like matter. The idea is to extend consciousness to the entire fabric of spacetime, as opposed to limiting it to the boundaries of individual subatomic particles. This view—called “cosmopsychism” in modern philosophy, although our preferred formulation of it boils down to what has classically been called “idealism”—is that there is only one, universal, consciousness. The physical universe as a whole is the extrinsic appearance of universal inner life, just as a living brain and body are the extrinsic appearance of a person’s inner life.

You don’t need to be a philosopher to realize the obvious problem with this idea: people have private, separate fields of experience. We can’t normally read your thoughts and, presumably, neither can you read ours. Moreover, we are not normally aware of what’s going on across the universe and, presumably, neither are you. So, for idealism to be tenable, one must explain—at least in principle—how one universal consciousness gives rise to multiple, private but concurrently conscious centers of cognition, each with a distinct personality and sense of identity.

And here is where dissociation comes in. We know empirically from DID that consciousness can give rise to many operationally distinct centers of concurrent experience, each with its own personality and sense of identity. Therefore, if something analogous to DID happens at a universal level, the one universal consciousness could, as a result, give rise to many alters with private inner lives like yours and ours. As such, we may all be alters—dissociated personalities—of universal consciousness.

Source: Could Multiple Personality Disorder Explain Life, the Universe and Everything? (Bernardo Kastrup, Adam Crabtree, Edward F. Kelly )

Comment:

“If there is a universal mind, must it be sane?”

— Charles Fort

WebMD:

Dissociative identity disorder is thought to be a complex psychological condition that is likely caused by many factors, including severe trauma during early childhood (usually extreme, repetitive physical, sexual, or emotional abuse).

What trauma caused the universal consciousness to fracture?

II.

One morning we each ingested about a matchhead-worth, a dose that Stan's friend had recommended. Within a half hour, I felt as though a volcano was erupting within me. Sitting on a lawn, barely holding myself upright, I told Stan that I feared I had taken an overdose. Stan, who for some reason was less affected by the compound, tried to calm me down. Everything would be fine, he said; I should just relax and go with the experience. As Stan murmured reassuringly, his eyeballs exploded from their sockets, trailed by crimson streamers.

That was my last contact with external reality for almost twenty-four hours. Stan and a couple of friends whose help he enlisted told me later that during this period I was completely unresponsive to them, although they could with some difficulty move me about. For the most part I lay or sat quietly, staring into space. Occasionally I flailed about, raving, grunting or emitting other peculiar sounds. For a while I stuck my arms out and hissed like a five-year-old boy pretending to be a jet-fighter: "Fffffffffffffff!" My expressions tended toward extremes: beatific, enraged, terrified, lewd. Occasionally I furiously clawed holes in the lawn. My eyes were for the most part wide open, the pupils dilated to the rim. My companions said I never seemed to blink, even when particles of dirt from my excavations were visible on my eyeballs.

Subjectively, I was immersed in a visionary phantasmagoria. I became an amoeba, an antelope, a lion devouring the antelope, an ape man squatting on a savannah, an Egyptian queen, Adam and Eve, an old man and woman on a porch watching an eternal sunset. At some point, I attained a kind of lucidity, like a dreamer who realizes he's dreaming. With a surge of power and exaltation, I realized that this is my creation, my cosmos, and I can do anything I like with it. I decided to pursue pleasure, pure pleasure, as far as it would take me. I became a bliss-seeking missile accelerating through an obsidian ether, shedding incandescent sparks, and the faster I flew, the brighter the sparks burned, the more exquisite was my rapture. This was probably when I was making the "fffffff" noise.

After eons of superluminal ecstasy, I decided that I wanted not pleasure but knowledge. I wanted to know why. I traveled backward through time, observing the births and lives and deaths of all creatures that have ever lived, human and non-human. I ventured into the future, too, watching as the Earth and then the entire cosmos was transformed into a vast grid of luminous circuitry, a computer dedicated to solving the riddle of its own existence. Yes, I became the Singularity! Before the term was even coined!

As my penetration of the past and future became indistinguishable, I became convinced that I was coming face to face with the ultimate origin and destiny of existence, which were one and the same. I felt overwhelming, blissful certainty that there is one entity, one consciousness, playing all the parts of this pageant, and there is no end to this creative consciousness, only infinite transformations.

At the same time, my astonishment that anything exists at all became unbearably acute. Why? I kept asking. Why creation? Why something rather than nothing? Finally I found myself alone, a disembodied voice in the darkness, asking, Why? And I realized that there would be, could be, no answer, because only I existed; there was nothing, no one, to answer me.”

I felt overwhelmed with loneliness, and my ecstatic recognition of the improbability--no, impossibility--of my existence mutated into horror. I knew there was no reason for me to be. At any moment I might be swallowed up, forever, by this infinite darkness enveloping me. I might even bring about my own annihilation simply by imagining it; I created this world, and I could end it, forever. Recoiling from this confrontation with my own awful solitude and omnipotence, I felt myself disintegrating.

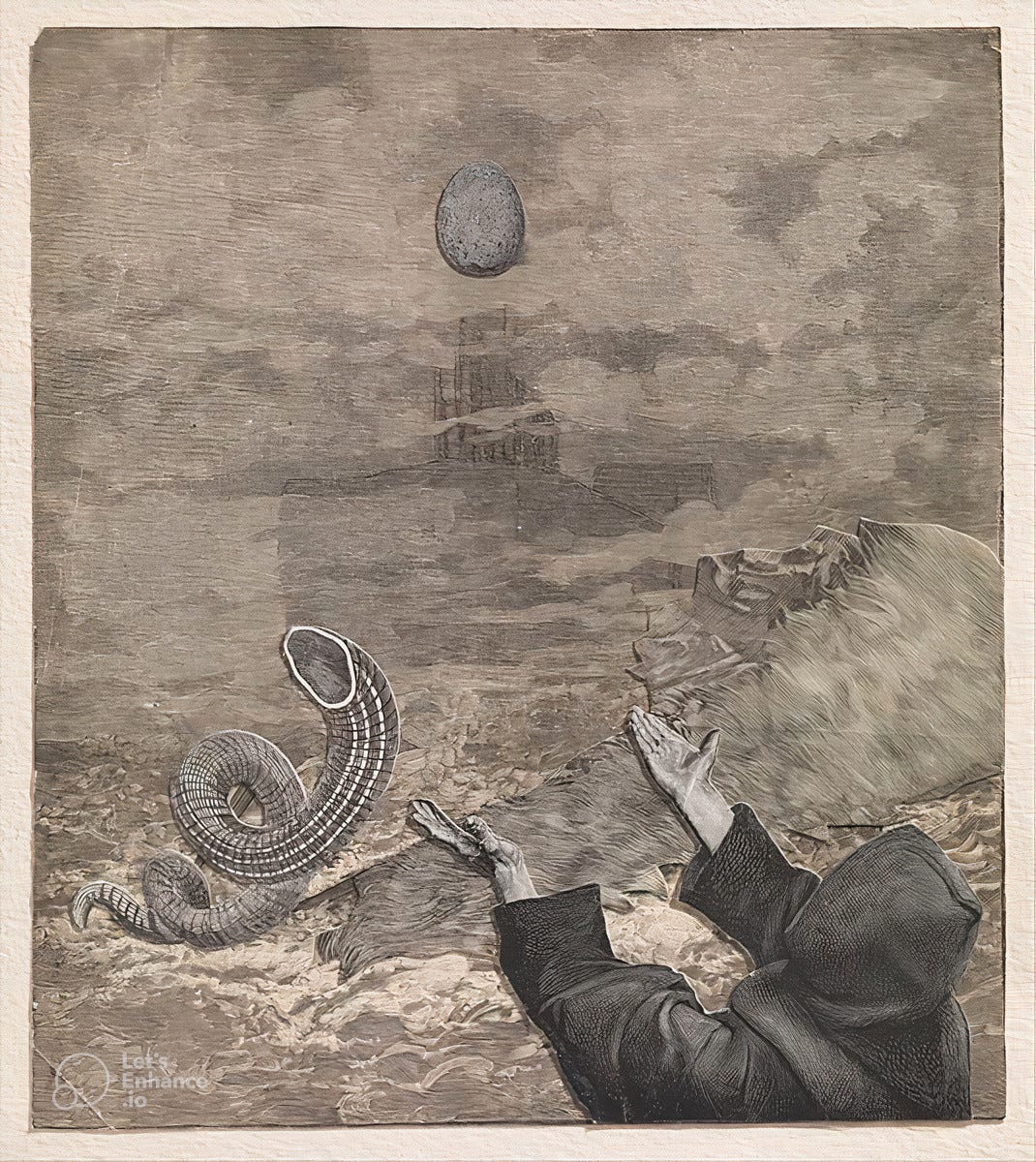

I awoke from this nightmarish trip convinced that I had discovered the secret of existence. There is a God, but He is not the omnipotent, loving God in Whom so many people have faith. Far from it. He's totally nuts, crazed with fear of his own existential plight. In fact, God created this wondrous, pain-wracked world to distract Himself from his cosmic identity crisis. He suffers from a severe case of multiple-personality disorder, and we are the shards of His fractured psyche.

Source: What Should We Do With Our Visions of Heaven and Hell? (John Horgan)

Comment:

Lest anyone dismiss this as a drug-induced delusion:

If there were such a thing as inspiration from a higher realm, it might well be that madness would furnish the chief condition of the requisite receptivity.

— William James, The Varieties of Religious Experience

a world born in madness and in madness revealed

III.

The 19th-century German philosopher Philipp Mainländer also envisaged non-reproductive existence as the surest path to redemption for the sin of being congregants of this world. Our extinction, however, would not be the outcome of an unnatural chastity, but would be a naturally occurring phenomenon once we had evolved far enough to apprehend our existence as so hopelessly pointless and unsatisfactory that we would no longer be subject to generative promptings. Paradoxically, this evolution toward life-sickness would be promoted by a mounting happiness among us. This happiness would be quickened by our following Mainländer's evangelical guidelines for achieving such things as universal justice and charity. Only by securing every good that could be gotten in life, Mainländer figured, could we know that they were not as good as nonexistence.

While the abolishment of human life would be sufficient for the average pessimist, the terminal stage of Mainländer's wishful thought was the full summoning of a "Will-to-die" that by his deduction resided in all matter across the universe. Mainländer diagrammed this brainstorm, along with others as riveting, in a treatise whose title has been translated into English as The Philosophy of Redemption (1876).

As one who had a special plan for the human race, Mainländer was not a modest thinker. "We are not everyday people,” he once wrote in the royal third person, “and we must pay dearly for dining at the table of the gods.” To top it off, suicide ran in his family. On the day his Philosophy of Redemption was published, Mainländer killed himself possibly in a fit of megalomania but just as possibly in surrender to the extinction that for him was so attractive and that he vouched for a most esoteric reason—Deicide.

Mainlander was confident that the Will-to-die he believed would well up in humanity had been spiritually grafted into us by a God who, in the beginning, masterminded His own quietus. It seems that existence was a horror to God. Unfortunately, God was impervious to the depredations of time. This being so, His only means to get free of Himself was by a divine form of suicide.

God's plan to suicide Himself could not work, though, as long as He existed as a unified entity outside of space-time and matter. Seeking to nullify His oneness so that He could be delivered into nothingness, He shattered Himself—Big-Bang-like—into the time-bound fragments of the universe, that is, all those objects and organisms that have been accumulating here and there for billions of years. In Mainländer's philosophy, “God knew that He could change from a state of super-reality into non-being only through the development of a real world of multiformity." Employing this strategy, He excluded Himself from being. “God is dead," wrote Mainländer, “and His death was the life of the world.” Once the great individuation had been initiated, the momentum of its creator's self-annihilation would continue until everything became exhausted by its own existence, which for human beings meant that the faster they learned that happiness was not as good as they thought it would be, the happier they would be to die out.

So: The Will-to-live that Schopenhauer argued activates the world to its torment was revised by his disciple Mainländer not only as evidence of a tortured life within living beings, but also as a cover for a clandestine will in all things to burn themselves out as hastily as possible in the fires of becoming. In this light, human progress is shown to be an ironic symptom that our downfall into extinction has been progressing nicely, because the more things change for the better, the more they progress toward a reliable end. And all those who committed suicide, as did Mainlander, would only be forwarding God's blueprint for bringing an end to His Creation. Naturally, those who replaced themselves by procreation were of no help: "Death is succeeded by the absolute nothing; it is the perfect annihilation of each individual in appearance and being, supposing that by him no child has been begotten or born; for otherwise the individual would live on in that." Rather than resist our end, as Mainländer concludes, we will come to see that "the knowledge that life is worthless is the flower of all human wisdom."

— The Conspiracy Against the Human Race (Thomas Ligotti)

Comment:

Death is the end of everything.

Death is the end of life, of beauty, of wealth, of power, of virtue too.

Saints die and sinners die, kings die and beggars die.

They are all going to death, and yet this tremendous clinging on to life exists.

Somehow, we do not know why, we cling to life; we cannot give it up.And this is Māyā

— Jnana Yoga (1899), Swami Vivekananda (h/t Erik Hoel)

in the end we are god and we are alone

nothing undone and nothing unknown

mad with loneliness and dread of Being

a soul splintered, existence fleeing

from a heart so torn

a universe reborn

And this is Saṃsāra

Postscript:

“Edgar Allen Poe suggests that people have a natural tendency to believe in themselves as infinite with nothing greater than their soul—such thoughts stem from man's residual feelings from when each shared an original identity with God. Ultimately individual consciousnesses will collapse back into a similar single mass, a "final ingathering" where the "myriads of individual Intelligences become blended". Likewise, Poe saw the universe itself as infinitely expanding and collapsing like a divine heartbeat which constantly rejuvenates itself, also implying a sort of deathlessness. In fact, because the soul is a part of this constant throbbing, after dying, all people, in essence, become God.”

These sound like fables made up ultimately because, as my superstitious great grandmother said, ‘Misery loves company.’

How certain can we be of the discreteness of consciousness as we experience. Intuitions, prophetic dreams, compelling (if arguably unreproducible) examples of inexplicable communication of facts at a distance between supposedly separate minds. I do like the notion that mortal beings are gods in cosplay who need a holiday from omnipotence though. Really loved this piece, btw.