INFINITE DICK

BOP #6

Previously: Dick was touched: a Trash Philosophy

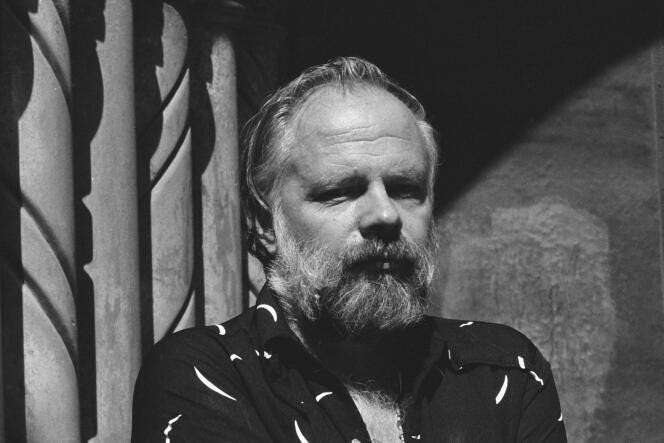

The Exegesis of Philip K. Dick contains the published selections of a journal kept by the science fiction writer Philip K. Dick. Dick started the journal after his visionary experiences in February and March 1974, which he called “2-3-74.”

…In the Exegesis, he theorized as to the origins and meaning of these experiences, frequently concluding that they were religious in nature. The being that originated the experiences is referred to by several names, including God, Zebra, and the Vast Active Living Intelligence System (VALIS). From 1974 until his death in 1982, Dick wrote the Exegesis by hand in late-night writing sessions, sometimes composing as many as 150 pages in a sitting. In total, it consists of approximately 8,000 pages of notes, only a small portion of which have been published.

In the next essay, I will delve further into the holy book that is the Exegesis and begin sketching the dogma (which is really an anti-dogma) of this new religion that we might provisionally dub “Dickianity”.

The crescendo of the Exegesis—the apotheosis of Dick’s quest for gnosis—was written some 6 1/2 years after Dick’s 2-3-74 theophany.

The following description of Dick’s November 17, 1980, “theophany” is arguably the single most important entry in the entire Exegesis: it offers a fully developed interpretation of Dick's mode of theoretical exploration, expressed in some of the most beautiful prose he ever wrote. In the face of despair at the interminability of his theological exploration, Dick meets a vision of a God at play: this entire theological exercise is presented as a game between omnipotent deity and a created being. Moreover, the infinitude of Dick's theories itself becomes proof that God is the beginning and end of his experiences. (editor’s note, Gabriel Mckee)

I will share the Infinity Game in full below, followed by a few further excerpts, before offering my own exegesis of Dick’s scripture.

God manifested himself to me as the infinite void; but it was not the abyss; it was the vault of heaven, with blue sky and wisps of white clouds. He was not some foreign God but the God of my fathers. He was loving and kind and he had personality. He said, “You suffer a little now in life; it is little compared with the great joys, the bliss that awaits you. Do you think I in my theodicy would allow you to suffer greatly in proportion to your reward?” He made me aware, then, of the bliss that would come; it was infinite and sweet. He said, “I am the infinite. I will show you. Where I am, infinity is; where infinity is, there I am. Construct lines of reasoning by which to understand your experience in 1974. I will enter the field against their shifting nature. You think they are logical but they are not; they are infinitely creative.”

I thought a thought and then an infinite regression of theses and countertheses came into being. God said, “Here I am; here is infinity.” I thought another explanation; again an infinite series of thoughts split off in dialectical antithetical interaction. God said, “Here is infinity; here I am.” I thought, then, an infinite number of explanations, in succession, that explained 2-3-74; each single one of them yielded up an infinite progression of flip-flops, of thesis and antithesis, forever. Each time, God said, “Here is infinity. Here, then, I am.” I tried for an infinite number of times; each time an infinite regress was set off and each time God said, “Infinity. Hence I am here.” Then he said, “Every thought leads to infinity, does it not? Find one that doesn’t.” I tried forever. All led to an infinitude of regress, of the dialectic, of thesis, antithesis and new synthesis. Each time, God said, “Here is infinity; here am I. Try again.” I tried forever. Always it ended with God saying, “Infinity and myself; I am here.” I saw, then, a Hebrew letter with many shafts, and all the shafts led to a common outlet; that outlet or conclusion was infinity. God said, “That is myself. I am infinity. Where infinity is, there am I; where I am, there is infinity. All roads — all explanations for 2-3-74 — lead to an infinity of Yes-No, This or That, On-Off, OneZero, Yin-Yang, the dialectic, infinity upon infinity; an infinity of infinities. I am everywhere and all roads lead to me; omniae viae ad Deum ducent. Try again. Think of another possible explanation for 2-3-74.” I did; it led to an infinity of regress, of thesis and antithesis and new synthesis. “This is not logic,” God said. “Do not think in terms of absolute theories; think instead in terms of probabilities. Watch where the piles heap up, of the same theory essentially repeating itself. Count the number of punch cards in each pile. Which pile is highest? You can never know for sure what 2-3-74 was. What, then, is statistically most probable? Which is to say, which pile is highest? Here is your clue: every theory leads to an infinity (of regression, of thesis and antithesis and new synthesis). What, then, is the probability that I am the cause of 2-3-74, since, where infinity is, there I am? You doubt; you are the doubt as in:

They reckon ill who leave me out;

When me they fly I am the wings.

I am the doubter and the doubt

“You are not the doubter; you are the doubt itself. So do not try to know; you cannot know. Guess on the basis of the highest pile of computer punch cards. There is an infinite stack in the heap marked INFINITY, and I have equated infinity with me. What, then, is the chance that it is me? You cannot be positive; you will doubt. But what is your guess?”

I said, “Probably it is you, since there is an infinity of infinities forming before me.”

“There is the answer, the only one you will ever have,” God said.

“You could be pretending to be God,” I said, “and actually be Satan.” Another infinitude of thesis and antithesis and new synthesis, the infinite regress, was set off.

God said, “Infinity.”

I said, “You could be testing out a logic system in a giant computer and I am — ” Again an infinite regress.

“Infinity,” God said.

“Will it always be infinite?” I said. “An infinity?”

“Try further,” God said.

“I doubt if you exist,” I said. And the infinite regress instantly flew into motion once more.

“Infinity,” God said. The pile of computer punch cards grew; it was by far the largest pile; it was infinite.

“I will play this game forever,” God said, “or until you become tired.”

I said, “I will find a thought, an explanation, a theory, that does not set off an infinite regress.” And, as soon as I said that, an infinite regress was set off. God said, “Over a period of six and a half years you have developed theory after theory to explain 2-3-74. Each night when you go to bed you think, ‘At last I found it. I tried out theory after theory until now, finally, I have the right one.’ And then the next morning you wake up and say, ‘There is one fact not explained by that theory. I will have to think up another theory.’ And so you do. By now it is evident to you that you are going to think up an infinite number of theories, limited only by your lifespan, not limited by your creative imagination. Each theory gives rise to a subsequent theory, inevitably. Let me ask you; I revealed myself to you and you saw that I am the infinite void. I am not in the world, as you thought; I am transcendent, the deity of the Jews and Christians. What you see of me in world that you took to ratify pantheism — that is my being filtered through, broken up, fragmented and vitiated by the multiplicity of the flux world; it is my essence, yes, but only a bit of it: fragments here and there, a glint, a riffle of wind . . . now you have seen me transcendent, separate and other from world, and I am more; I am the infinitude of the void, and you know me as I am. Do you believe what you saw? Do you accept that where the infinite is, I am; and where I am, there is the infinite?”

I said, “Yes.”

God said, “And your theories are infinite, so I am there. Without realizing it, the very infinitude of your theories pointed to the solution; they pointed to me and none but me. Are you satisfied, now? You saw me revealed in theophany; I speak to you now; you have, while alive, experienced the bliss that is to come; few humans have experienced that bliss. Let me ask you, was it a finite bliss or an infinite bliss?”

I said, “Infinite.”

“So no earthly circumstance, situation, entity or thing could give rise to it.”

“No, Lord,” I said.

“Then it is I,” God said. “Are you satisfied?”

“Let me try one other theory,” I said. “What happened in 2-3-74 was that — ” And an infinite regress was set off, instantly.

“Infinity,” God said. “Try again. I will play forever, for infinity.”

“Here’s a new theory,” I said. “I ask myself, ‘What God likes playing games? Krishna. You are Krishna.” And then the thought came to me instantly, “But there is a god who mimics other gods; that god is Dionysus. This may not be Krishna at all; it may be Dionysus pretending to be Krishna.” And an infinite regress was set off.

“Infinity,” God said.

“You cannot be YHWH who You say You are,” I said. “Because YHWH says, ‘I am that which I am,’ or, ‘I shall be that which I shall be.’ And you — ”

“Do I change?” God said. “Or do your theories change?”

“You do not change,” I said. “My theories change. You, and 2-3-74, remain constant.”

“Then you are Krishna playing with me,” God said.

“Or I could be Dionysus,” I said, “pretending to be Krishna. And I wouldn’t know it; part of the game is that I, myself, do not know. So I am God, without realizing it. There’s a new theory!” And at once an infinite regress was set off; perhaps I was God, and the “God” who spoke to me was not.

“Infinity,” God said. “Play again. Another move.”

“We are both Gods,” I said, and another infinite regress was set off. “Infinity,” God said. “I am you and you are you,” I said. “You have divided yourself in two to play against yourself. I, who am one half, I do not remember, but you do. As it says in the Gita, as Krishna says to Arjuna, ‘We have both lived many lives, Arjuna; I remember them but you do not.’ And an infinite regress was set off; I could well be Krishna’s charioteer, his friend Arjuna, who does not remember his past lives.” “Infinity,” God said. I was silent. “Play again,” God said.

“I cannot play to infinity,” I said. “I will die before that point comes.”

“Then you are not God,” God said. “But I can play throughout infinity; I am God. Play.”

“Perhaps I will be reincarnated,” I said. “Perhaps we have done this before, in another life.” And an infinite regress was set off.

“Infinity,” God said. “Play again.”

“I am too tired,” I said.

“Then the game is over.”

“After I have rested — ”

“You rest?” God said. “George Herbert wrote of me:

Yet let him keep the rest,

But keep them with repining restlessnesse.

Let him be rich and wearie, that at least,

If goodness leade him not, yet wearinesse

May tosse him to my breast.

“Herbert wrote that in 1633,” God said. “Rest and the game ends.”

“I will play on,” I said, “after I rest. I will play until finally I die of it.”

“And then you will come to me,” God said. “Play.”

“This is my punishment,” I said, “that I play, that I try to discern if it was you in March of 1974.” And the thought came instantly, my punishment or my reward; which? And an infinite series of thesis and antithesis was set off.

“Infinity,” God said. “Play again.”

“What was my crime?” I said, “that I am compelled to do this?”

“Or your deed of merit,” God said.

“I don’t know,” I said.

God said, “Because you are not God.”

“But you know,” I said. “Or maybe you don’t know and you’re trying to find out.” And an infinite regress was set off.

“Infinity,” God said. “Play again. I am waiting.”

Soon after the Infinity Game entry, Dick writes:

Here is the secret and perpetual and ever-growing victory by God over his adversary as he (God) defeats him (Satan) again and again in the game they play — the cosmic dialectic that I saw. This is enantiodromia at its ultimate: the conversion of the irreal to the real. In my case it was the conversion of “the human intellect will not lead to God but will lead only deeper and deeper into delusion” into its mirror opposite: “The human intellect, when it has pushed to infinity, will at last, through ever deepening delusion, find God.” Thus I am saved: and know that I did not start out seeing God (2-3-74) (which led to this 6½ year exegesis): but, instead, wound up finding God (11-17-80) — an irony that Satan did not foresee. And thus the wise mind (God) wins once again, and the game continues. But someday it will end.

Editor’s note:

The visionary episode of November 17, 1980, is one of the peaks of the Exegesis, as sublime a modern parable as Kafka’s “Before the Law.” These pages are also bona fide mysticism — not because Dick had authentic mystical experiences (whatever those are) but because Dick produced powerful texts that twist and illuminate vital strands of mystical discourse. Here we are in the apophatic realm of the via negativa, which, like Dick’s gameplaying God, deconstructs all names and forms in the obscure light of the infinite. Elsewhere Dick tips his hat to Eckhart and Erigena, but the apophatic mystic his writing most invokes here is Nicholas of Cusa (1401–1464). By analyzing paradoxes, Cusa pushed reason toward a “learned ignorance” (docta ignorantia) that blooms finally into the coincidentia oppositorum, or coincidence of opposites — a mystic coincidence that Dick achieves here through a manic and corrosive intensification of the dialectic. But perhaps the most paradoxical aspect of Dick’s 11/17/80 account is that his God here has nothing to do with the divine abyss of the negative mystics. Instead, he is a character in a story: part playful guru, part Yahweh, screwing around with Adam because there is nothing better to do. (Erik Davis)

A little more than a month before the Infinity Game (10/22/1980), Dick writes:

Probably the wisest view is to say: the truth—like the Self — is splintered up over thousands of miles and years; bits are found here and there, then and now, and must be re-collected; bits appear in the Greek naturalists, in Pythagoras, Plato, Parmenides, Heraclitus, Neoplatonism, Zoroastrianism, Gnosticism, Taoism, Mani, orthodox Christianity, Judaism, Brahmanism, Buddhism, Orphism, the other mystery religions. Each religion or philosophy or philosopher contains one or more bits, but the total system interweaves it into falsity, so each as a total system must be rejected, and none is to be accepted at the expense of all the others (e.g., “I am a Christian” or “I follow Mani”). This alone, in itself, is a fascinating thought: here in our spatiotemporal world we have the truth but it is splintered—exploded like the eide—over thousands of years and thousands of miles and (as I say) must be recollected, as the Self or Soul or eidos must be. This is my task.

In that case, each given system is in itself part of the enslaving snare of delusion; in other words, as soon as I avow one philosopher or system (e.g., Spinoza or Schopenhauer or Kant or Anaxagoras or Parmenides or Gnosticism) I have become again or more ensnared, as I am by this spatiotemporal world itself; it is as if the eidos of Truth is exploded and splintered like all the eide….Of course this means that I can never come up with the whole, true, complete explanation or answer. The truth is splintered! (In addition to the places I listed above where I’ve found bits of the truth I should add: the Hermetics and the Kabbalah and quantum mechanics.)

Editor’s note:

Dick has in effect become a super-comparativist, and so he is able to draw connections and organize disparate patterns of information, like Valis, through huge stretches of space and time. And why not?…In this particular passage, the double-edged sword of the comparative imagination is evident: bits of truth can indeed be found everywhere, but the full truth is nowhere to be found; religious systems are both true (as approximations or reflections) and false (as final and complete answers) at the same time. Today a much simpler form of this double-notion is crystallized in the oft heard quip “spiritual, but not religious.” Such a position is often demeaned as fuzzy, as narcissistic as “New Agey”. In fact, it constitutes a quiet, but radical, rejection of religion in all its dogmatic and dangerous forms. (Jeffrey Kripal)

I have, for rhetorical purposes and simplicity’s sake, been somewhat misleading in claiming that I will attempt to derive a religious system from Dick’s thought, a body of thought which, as should now be apparent, is directly antithetical to religion and system. But if not religion, then what is this “Dickianity”?

It is true spirituality, distilled into absolute essence, into its rawest and purest form. It is a spirituality not of meditative repose and vague, toothless beliefs, but of (metaphysical) theorizing, of skepticism and criticism, of an open-ended and never-ending search for knowledge (for gnosis) that is always at the beginning of infinity (a la Deutsch). In this, it has come to resemble a science, and in doing so speaks to Metzinger’s claim that, “the opposite of religion is not science, but spirituality”.

Religion would now consist in the deliberate cultivation of a delusional system, the standpoint of pure belief, the dogmatic or fideist refusal of an ethics of inner action. By contrast, spirituality would be the epistemic stance focused on the attainment of knowledge. Religions organize and evangelize. Spirituality is something radically individual and typically, it is rather quiet.

(“Spirituality and Intellectual Honesty”)

The difference between science and Dick’s true spirituality is in the standard against which theories are evaluated: in the former, empirical; in the latter, mystical (how well do the theories “eff” one’s own ineffable revelatory experiences and those of others throughout history?), theological (how well do one’s theories affirm the world’s religious traditions, and more importantly, innovate on them?), and pragmatic—what are the fruits of your doctrines, what acts do they inspire, what kind of creature do they create?

William James proposed a pragmatic “fruit” test for determining true mystical doctrines (James 1958, 368): if a mystical experience produces positive results in how one leads one’s life, then the experience is authentic and the way of life one follows is vindicated, and so the teachings leading to the positive life are correct. In short, the “truth” of one’s beliefs are shown by one’s life as a whole. (SEP, “Mysticism”)

The truth of our Phallic Prophet’s revelation is born out in the stupendous effort which he threw into his quest to know God…

I am tired. I've labored for over six and a half years to fathom 2-3-74. I have been relentlessly skeptical and relentlessly imaginative and I have done enormous research and tried out as many possible theories as I could come up with….

Okay. The one billionth fresh start. All of it — 2-74–2-75 — and what the AI voice has said, and all the revelations and visions — it’s all indubitably this: soteriology. That is clear.1

…in the way in which his philosophy prepared him for death (as all true philosophy should)…

…The real success of the exegesis is that as I become old, now, and wear out, I feel myself wearing out only as an instance of an eternal soul or form; that nothing is lost, nothing is destroyed; and although I don’t crave immortality I do crave vigor and joy and the running that I associate with my eidos. And I know, too, that all that I have lost in my life is epiphenomenal, people and cats and things, that in reality nothing is lost. So I can face my own aging and mortality with calm and even pleasure, since I am grounded in both a mystical vision of super reality and an intellectual exegesis based on that vision, the totality of which provides me with a philosophy and with an experience with world that is harmonious and wonderful and intellectually satisfying: it is a vision of intactness, of my own self and world. Of everything as a negentropic whole. As regards my writing: it will permanently affect the macro-meta-somakosmos in the form of reticulation and arborizing — and hence will survive in reality forever, in the underlying structure of the world order.

…and in the tremendous creative output inspired by 2-3-74 (A Scanner Darkly, VALIS, The Divine Invasion, The Transmigration of Timothy Archer).

The distinction between static and dynamic religion from Henri Bergson’s The Two Sources of Morality and Religion is useful here. Static religion, and the closed morality which it entails, is ultimately concerned with survival and social cohesion and war, and thus obedience and stability. In contrast, dynamic religion (and we may think of Dickianity as the most dynamical religion imaginable) is concerned with creativity and progress of all forms. It entails an open morality that “is genuinely universal and aimed at peace”. The source of the open morality is what Bergson calls “creative emotions”.

The difference between creative emotions and normal emotions consists in this: in normal emotions, we first have a representation which causes the feeling (I see my friend and then I feel happy); in creative emotion, we first have the emotion which then creates representations. So, Bergson gives us the example of the joy of a musician who, on the basis of emotion, creates a symphony, and who then produces representations of the music in the score…The creative emotion makes one unstable and throws one out of the habitual mode of intelligence, which is directed at needs. Indeed, in The Two Sources, Bergson compares creative emotions to unstable mental states as those found in the mad. But what he really has in mind is mystical experience. For Bergson, however, mystical experience is not simply a disequilibrium. Genuine mystical experience must result in action; it cannot remain simple contemplation of God. This association of creative emotions with mystical experience means that, for Bergson, dynamic religion is mystical. Indeed, dynamic religion, because it is always creative, cannot be associated with any particular organized set of doctrines. A religion with organized—and rigid—doctrines is always static. (SEP, “Henri Bergson”)

Dick’s revelation is declared in the star-blast of his creative spirit, its truth testified in the sun-fire of his imagination.

Though Dick was influenced by nearly every religion there is and was, his thought was most indebted to Gnosticism (as he himself recognized), and it would not be inaccurate to think of Dickianity as a revival and syncretic remix of this lost spiritual tradition.

The characterization of Gnosticism as a heretical foil to Christianity (a self-serving characterization promoted by ancient and modern Christians2) invites an assumption of equivalence between the two that is actively misleading. Gnosticism is not so much a religion as a spiritual form, a kind of a “meta-religion” defined by a certain devotional ethos and philosophical posture rather than specific doctrines or moral precepts. The most appropriate contrast is not Christianity or any other religion, but fundamentalism.

The defining attributes of this spiritual form, according to April DeConick, are mystical practices, a transgressive esotericism and hermeneutics, a belief in an innate spiritual nature, a quest orientation, and inclusive metaphysics. All of these are present in this New Gnosticism along with some additional accents and flavors unique to Dick.3

Gnosis

The sine qua non of Dickianity, the only necessary and sufficient clause, is a belief in the possibility of gnosis and an aspiration to it. All else is incidental, subject to revision and abolition.

A strictly materialist or historical understanding of the human being is not part of the solution. It is part of the problem. It is part of the trap. To make any real sense of our place in the cosmos and, more importantly still, to change that place, we must be open to genuine transcendence and the abolition of time through its conversion into space. Does this make any sense to our sense-based understanding and its three-dimensional categories? No. If it did, it would not lie outside these three dimensions, would it? In the end, then, Dick’s gnosis as expressed here is not an argument or a thesis. It is a revelation. And this, of course, is exactly what he claimed. (editor’s note, Jeffrey Kripal)

Quest

There are no “followers” in Dickianity, only leaders; all Dickians are bold explorers on a quest through a pathless land.

I maintain that Truth is a pathless land, and you cannot approach it by any path whatsoever, by any religion, by any sect…Truth, being limitless, unconditioned, unapproachable by any path whatsoever, cannot be organized; nor should any organization be formed to lead or to coerce people along any particular path…As I have said, I have only one purpose: to make man free, to urge him towards freedom, to help him to break away from all limitations…That is the only way to judge: in what way are you freer, greater, more dangerous to every society which is based on the false and the unessential? (Jiddu Krishnamurti4)

Spiritual progression is measured in creation.

Like circles of artists today, gnostics considered original creative invention to be the mark of anyone who becomes spiritually alive. Each one, like students of a painter or writer, was expected to express his own perceptions by revising and transforming what he was taught. Whoever merely repeated his teacher’s words was considered immature…On this basis, they expressed their own insight—their own gnosis—by creating new myths, poems, rituals, “dialogues” with Christ, revelations, and accounts of their visions. (The Gnostic Gospels, Elaine Pagels)

The Exegesis is Dick’s gnostic gospel.

There is no way to overestimate or repeat enough this exegetical fact: for Dick, writing and reading are the privileged modes of the mystical life. His is a mysticism of language, of Logos, of the text-as-transmission, of the science fiction novel as coded Gnostic scripture. The words on the page, on his late pages at least, are not just words. They are linguistic transforms of his own experience of Valis. They are mercurial, shimmering revelations. They are alive. And—weirdest of all—they can be “transplanted” into other human beings, that is, into you and me via the mystical event of reading. Here, in this most stunning of Dick’s notions, the cheap science fiction novel becomes a Gnostic gospel, words become viral, reading a kind of mutation, and the reader a sort of symbiote. (editor’s note, Jeffrey Kripal)

Game

It is not merely the object of the quest that is divine, but the very quest itself. In this, the quest more closely resembles a game, an infinite game we play with God, the Infinite Player.

The solution to the puzzle is the act of solving it, since this is play. When you realize this, you understand that in playing, there is no “means-end” — the act is the goal. Just as he once taught us love, he now teaches us to play. There is as great a potential for spiritual significance in play as there is in power, wisdom, love, beauty.

…Could the new attribute of God — revealed to us now — be that he plays, at games? This is a long way from Sinai. Trickster God — like Krishna. Power, wisdom, love, beauty, and now play — guessing games, only guessing games.

Paradox

The gnostic game-quest is interminable because we are created beings that can never fully comprehend the nature of the divine and because the Godhead is an eternally evolving dialectical paradox unknowable even to itself.5

What is the total context in which the unmerited suffering and death of living creatures can be coherently understood?…I’ve been shown a really perplexing paradox. The highest good is the “harmonious fitting together of the beautiful” — i.e., Pythagoras’ kosmos, and this is what God moves everything toward. Okay. And then I’ve been shown the cost at which this is achieved — the torture and killing of the epicreatures, and I am shown that this cost is too great! So the summum bonum can only be achieved at a cost that (spiritually speaking) makes it not worth it (i.e., unacceptable). Then is the summum bonum actually the summum bonum? How can it be? Isn’t there a logical contradiction here? Right! There sure is! This is the dramatic tragedy of the universe, of God, of all: process, reality, and goal (teleology). Okay, then the real summum bonum lies in saving the epicreatures (i.e., the parts which go together to make the whole). The whole is not greater than the sum of its parts; no: each and every part (ontogon) is more important than the whole! So within the summum bonum there is a secret. A mysterious conversion occurs. The part is the real whole. Perhaps this is an irreconcilable Irish bull which sets off the infinite flip-flops of the dialectic; maybe this particular paradox is the primal imbalance that is the dynamism driving reality on //\//\//\//\//\//\//\ forever; it cannot ever be resolved, so process never ends (which is good).

//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\

I will never know if I know the truth (it won’t say) but this binary computer idea is a good one — it and its games, where every theory is true and not true equally. Damn educational game! Boy, is my mind stretched. And I’ve done it to others in my writing. Yes, it is (1) occluding and enslaving us and (2) educating, improving and liberating us. Shit. Well, I guess that’s how it goes it in the realm of mutually canceling paratruths (Y=Ȳ).

//\

It’s evil.

It’s good.

//\

It’s occluding.

It’s educating.

//\

It’s alive.

It’s a machine.

//\

It’s deadly serious.

It’s playful.

//\

It created and creates our reality.

It evolved out of our reality.

//\

It’s objectively real.

It’s just my own head.

//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\

//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\

Dick beat the game.

The game beat Dick.

//\

Dick was only a man.

Dick was not only a man.

//\

Dick was God.

I am time without end. I am the sustainer. I am the death that snatches all. I am the source of all that shall be born. I am glory, prosperity, beautiful speech, memory, intelligence, steadfastness and forgiveness. I am the dice play of the cunning. I am the strength of the strong. I am triumph and perseverance. I am the purity of the good. I am the silence of things secret. I am the knowledge of the knower. I am the divine seed of all that lives.

Dick was Satan.

I see the legend of Satan in a new way. Satan desired to know God as fully as possible. The fullest knowledge would come if he became God, was himself God. He strove for this and achieved it, knowing that the punishment would be his permanent exile from God. But he did it anyhow, because the memory of knowing God, really knowing him as no one else ever had or would, justified to him his eternal punishment. Now, who would you say truly loved God out of everyone who ever existed? Satan willingly accepted eternal punishment and exile just to know God—by becoming God—for an instant. Further (it occurs to me) Satan knew God, truly knew God, but perhaps God did not know or truly understand Satan; had he understood him he would not have punished him. But Satan welcomed that punishment, for it was his proof to himself that he knew and loved God.

DICK WAS INFINITE.

DICK WAS DICK.

8=====D~~

//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\

//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\//\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\

This last paragraph was from an entry written a month before Dick’s death in February 1982. Gabriel Mckee, editor’s note:

By its very nature, the Exegesis has no conclusion. And yet here, so close to the final pages Dick wrote, he hits upon a definitive truth of his experiences and their interpretation. Whatever the reigning theory of the moment, Dick is always concerned with deliverance, liberation, rescue. Whatever bonds might restrict the individual being—dogma, karma, astral determinism, sin, demiurgic imprisonment—Dick wants to see them broken and the being released into an absolute, ontological freedom. The Exegesis is a record of a human soul in search of salvation.

From “The Countercultural Gnostic: Turning the World Upside Down and Inside Out” (DeConick, 2016):

Gnosticism then has been characterized by scholars as a perversion of pristine Christianity (which is identified with emergent Catholicism or normative Christianity) and a dangerous heresy to boot. This understanding of gnosticism is still popular today because it reinforces the triumphant story of conventional Christianity that many Christians prefer. For instance, Darrell Bock, writing in 2006, argues that the diversity of gnosticism proves its “parasitic” quality. It is not a “legitimate” development of the Christian faith. According to Philip Jenkins in his 2001 publication, gnostic texts are “heretical texts” with “an odd slant” unconcerned with “historical realities.” Because of this aberrant perspective, “they arouse widespread excitement among feminists and esoteric believers, and aspiring radical reformers of Christianity.” They represent “a vital weapon in the liberal arsenal.”

For further discussion of Gnosticism see my recent essay, “The Most Dangerous Idea”.

Krishnamurti may be regarded as a forerunning prophet of Dickianity (if you haven’t heard of Krishnamurti it’s worth reading a bit about him, one of the crazier life stories you’ll ever encounter).

Dick certainly puts his own spin on it, but this conception of God has its origin with Jakob Böhme (as Dick himself acknowledged).

About 400 years ago, before the discovery of electricity and only 150 years after the invention of the printing press, a barely literate German cobbler came up with the idea that God was a binary, fractal, self-replicating algorithm and that the universe was a genetic matrix resulting from the existential tension created by His desire for self-knowledge. (source)

On the Krishnamurti front, it is worth reading about UG as well. https://medium.com/original-philosophy/who-is-ug-krishnamurti-d1f23e801be0