The Tale of the Shaman: Science, Magic, and Super Placebo (v2)

...

Programming note: I will be very busy with work for the next month or so and not able to write as much as I'd like so I figured I would repost some older essays that (judging by the pageviews) many of my subscribers haven’t read yet. This is one of my favorites, originally released in January 2022. I’ve made a few cosmetic changes and included a postscript highlighting an interesting new study that speaks to the themes of this essay. Enjoy!

David Abram is something of a bizarro World’s Most Interesting Man.

Born in the suburbs of New York City, Abram began practicing sleight-of-hand magic during his high school years in Baldwin, Long Island; it was this craft that sparked his ongoing fascination with perception. In 1976, he began working as "house magician" at Alice's Restaurant in the Berkshires of Massachusetts and soon was performing at clubs throughout New England while studying at Wesleyan University. After his second year of college, Abram took a year off to travel as an itinerant street magician through Europe and the Middle East; toward the end of that journey, in London, he began exploring the application of sleight-of-hand magic to psychotherapy under the guidance of Dr. R. D. Laing. After graduating summa cum laude from Wesleyan in 1980, Abram traveled throughout Southeast Asia as an itinerant magician, living and studying with traditional, indigenous magic practitioners (or medicine persons) in Sri Lanka, Indonesia, and Nepal. Upon returning to North America he continued performing while devoting himself to the study of natural history and ethno-ecology, visiting and learning from native communities in the Southwest desert and the Pacific Northwest. A much-reprinted essay written while studying ecology at the Yale School of Forestry in 1984 — entitled "The Perceptual Implications of Gaia" — brought Abram into association with the scientists formulating the Gaia Hypothesis; he was soon lecturing in tandem with biologist Lynn Margulis and geochemist James Lovelock both in Britain and the United States. In the late 1980s, Abram turned his attention to exploring the decisive influence of language upon the human senses and upon our sensory experience of the land around us. Abram received a doctorate for this work from the State University of New York at Stony Brook, in 1993.

In his book Becoming Animal, Abram shares a remarkable story about a shamanic healing technique he observed while trekking through the Himalayas.

“In the course of these first months in the Himalayas I came into contact with several jhankris (Nepalese shamans) of very diverse skills, and I lived for several weeks with two of them, a husband and wife who were both highly regarded as healers…I soon found myself accompanying the man, Dorjee, to a range of healings—usually in the evening and sometimes lasting the whole night. Some of the healings were much stronger, in their feel, than others. In the most intense sessions Dorjee, aided by the rhythmic pounding on his dhyangro (a large two-sided drum), slipped into a kind of delirium. Meanwhile, during the days, I shared with him some basic techniques central to my practice of legerdemain, painstakingly walking his fingers through the most elementary sleights. However, apart from letting me attend the healings, the jhankri shared little or nothing of his craft with me. Much of what unfolded during the healing sessions was entirely opaque to my understanding…

… But then, at the frenzied height of one such session, I was startled to see the shaman extract a bloody, tumor-like knot of matter from the side of a feverish woman's abdomen. It was a remarkable happening, and had a powerful effect upon those watching. Only then did I realize that certain sleight-of-hand methods were already a part of Dorjee's toolkit. For my conjuror's eyes had glimpsed that bloody gizzard hidden in Dorjee's palm for several moments before it was extracted from the client's body. The more I thought about it, the more I wondered whether Dorjee drew upon such legerdemain that evening simply because I was watching, as a way of displaying his own skill at something akin to my craft. When we were alone two days later I cautiously inquired about the extraction, praising his skill yet making clear I had seen the deception involved. The shaman took no offense. Such a technique can be used, he said, only when other approaches will not work. I waited for him to explain. Here is what is what he shared, at least as far as I could understand (putting here into my terms what he conveyed not only with words but with many gestures and facial grimaces).

There are certain demons whose grip on a sick person's innards is so firm, so tenacious, that they cannot be dispelled by the jhankri's phurba (a sort of magic dagger), or by any other means. No amount of trancework can induce such a demon to loosen its grip. It is in such cases that the jhankri must employ a bit of subterfuge to trick the demon out of the client's body. For that malevolent knot of energy will not depart its host's body unless it is provided with another physical body to inhabit. This can be a smallish object, as long as it is suitably sanguine to attract the demon (demons apparently love gruesomeness and gore). The bloody gizzard of a large bird will do nicely.

But here's the rub: The demon must not be allowed to catch sight of this object beforehand, lest the demon become suspicious and realize the trap that is being set for it. Since a demon perceives the world through the senses of whatever body it currently possesses, the jhankri must therefore keep that bloody gizzard entirely hidden from the patient's eyes. Once the patient herself has been lulled into a trance by the jhankri's drumming and dancing, then the demon within her will also be in a trance, and so can be gradually lured up out of the innards toward the body's surface, or skill by various means. It is then, and only then, that the gory object must come into view, at that precise spot on the patient's skin—as though it were being extracted from her body. For then the unsuspecting demon will be unable to resist being drawn across the skill by the proximity of the delectable, gristly form that has lust appeared there. It's as though that bloody gizzard or other object effectively sucks the demonic spirit into itself. The jhankri can now display that bloody object to the patient and the others present, before tossing it into the fire. If the patient recovers from her illness, the jhankri will know, that the sleight-of-hand was effective, not in tricking the patient (as a Westerner might claim) but in tricking the demon—the actual illness—itself!

Dorjee was wholly earnest in his conviction that it was the demon who was being deceived, not the client or the client's family… Dorjee insisted that I accompany him eight or nine days later to the village of the woman who'd received the treatment that evening. She was tilling one of the village fields when we arrived. She affirmed that the long-standing, debilitating pain in her midriff had eased and then gone away in the days following the healing, and had not returned. Her energy, meanwhile, had been slowly and steadily renewing itself; she felt well.

The healing by Dorjee was one of several uses of perceptual legerdemain that I have witnessed by traditional medicine persons. I came to believe that the shamanic application of sleight-of-hand for healing purposes is likely the aboriginal source of the entire craft of sleight-of-hand conjuring. For the skillful practice of sleight-of-hand magic is a kind of shock treatment for the person watching—a way of jarring his nervous system, and immune system, via the direct conduit of his senses. It is a potent technique for disrupting frozen patterns and fears, knocking loose the regenerative capacity of the body. Contrary to modern assumptions, sleight-of-hand conjuring probably originates not as an illusory depiction of supernatural events, but as a practical technique for unlocking and activating the fluid magic of nature itself.”

Scientific materialist translation: magical healing techniques are psychosocial technologies for eliciting superordinary placebo responses.

II.

After reading this story, I tried to place myself in the woman’s shoes and imagine how I would react to Dorjee’s healing technique. My sense (and maybe I’m giving myself too much credit here) is that “amused skepticism” is the best description of how I’d feel. I, a scientifically educated modern man, simply would not believe that a shaman had extracted a bloody mass from my body with no discernible wound; my entire metaphysical and epistemological schema rules this out a priori. However, to Dorjee and the sick woman, the inverse was true—they both knew, unequivocally, that demons existed, that they caused sickness, and that it was possible to lure them out of the body with certain techniques.

To use the parlance of the epigraphical tweet, I am hopelessly “stuck to the bottom” of the magical continuum. My philosophical constitution (in less pretentious terms, my worldview) is such that there are certain psychological states of absolute belief and unity of will which I am fundamentally incapable of reaching. It is my inability to inhabit these “enchanted” states of mind that prevents me from “activating the fluid nature of magic” (a.k.a. the placebo effect).

A tell-tale sign that I am a deeply unmagical person is the fact that I am writing an essay on how to scientifically explain magic. This is something that only a child of a disenchanted world even think about attempting.

Max Weber used the German word Entzauberung, translated into English as “disenchantment” but which literally means “de-magic-ation.” More generally, the word connotes the breaking of a magic spell. For Weber, the advent of scientific methods and the use of enlightened reason meant that the world was rendered transparent and demystified. Theological and supernatural accounts of the world involving gods and spirits, for example, ceased to be plausible. Instead, one put one’s faith in the ability of science to eventually explain everything in rational terms. But, for Weber, the effect of that demystification was that the world was leached of mystery and richness. It became disenchanted and disenchanting, predictable and intellectualized.

In a disenchanted world, the nature of belief itself is transformed such that the psychological states of absolute belief which enable magic are no longer attainable.

In the old world, people could have a naive belief, but today belief or unbelief is "reflective", and includes a knowledge that other people do or do not believe. We look over our shoulder at other beliefs…

—Charles Taylor, A Secular Age

All of this paints a grim picture for the prospect of magic in modernity. The emergence of the secular materialist paradigm during the Enlightenment marked a fundamental shift from a magical age to a scientific one. Once we began to “look over our shoulders at other beliefs”, the spell was broken—the psychosomatic states which enable magical effects were irrevocably compromised. This is not to say that magic is now impossible, only that it is now necessarily a rare and elusive thing, inaccessible by those who have been too tainted by modern scientific paradigm like myself. Dorjee was still able to use his magical healing technique in the 1980s (when the story occurred, according to Abram), however this was likely only possible because Dorjee lived in an incredibly remote part of the Himalayas. While I can’t say for sure, the impression given in Abram’s book is that the culture of his people was still highly insulated from modernity; perhaps they knew the general picture of what it was like, but did not yet have a clear enough view for the spell to be fully broken.

(Note: I am painting with a very broad brush here and I certainly don’t think that all magical phenomenon can be easily explained away as manifestations of the placebo effect, or that the placebo effect is this simple, one dimensional psychosomatic response, but in the interest of brevity and focus I will save those discussions for another time.)

III.

“Enchanted psychological states” might sound a little spooky and hand-wavy (and it is), but I think we can understand how the effects of these states manifest in very real, but subtle changes to behavior and cognition. We can imagine a charlatan shaman performing the same techniques but with the most minute differences in facial expressions, body language, and intonation due to the fact that their mind is not truly inhabiting this state of absolute belief—no matter how much the charlatan wants to convince herself that she has magical powers, a part of her will always know it is bullshit. These minute differences in behavior, whether consciously perceived by the patient or not, would change the entire psychological dynamic of the magical operation and thereby render it ineffective (i.e. no super-ordinary placebo effect is elicited). This all might sound a little more fantastical than it is really is—what I am speaking of is bedside manner, something that is already known to modulate the power of the placebo effect. There is a big difference between a doctor who is genuinely confident, caring, and compassionate and one who is simply faking it (and some part of you can always tell the difference).

The psychosocial context of the magical act is also crucial to its success. To understand this, let’s put ourselves in the woman’s shoes. The jhankri is a man who you believe to have supernatural powers (see below) and who is regarded with respect and a degree of fear by everyone you know. You’ve heard tales about his otherworldly powers (e.g. communicating with spirits while in a trance state, a common feature of shamanic practices the world over) and healing prowess and this gives you hope, something you desperately need as nothing else has helped to ease your terrible pain. As you approach his home, your fear, anxiety, and hopefulness rise to a crescendo, creating a highly charged mental state which primes you for psychosomatic healing.

All of the beliefs, emotions, and experiences described in the previous paragraph set the stage for the final stage of the magical act. The jhankri performs a complex multi-sensory ritual designed to enhance this charged psychological state even further. The performance builds and builds until !!!!!!—he pulls a bloody mass from the area where you have been feeling pain. Afterward, he declares that the demon has been exorcised and that you will soon begin to feel better. Sure enough, he is right.

There is a book, The Death and Resurrection Show: From Shaman to Superstar, which argues that indigenous shamanism is the forebearer of modern show business (highlighted in this excellent essay by Drew Schorno); this account would certainly lend credence to the idea. It’s not all fun and games though. Around 10 years before this story took place, the cult leader Jim Jones (he of the Jonestown Massacre) was using the same “healing” technique as the jhankri in service of very different kind of “show”.

“Jim Jones was a tremendous performer. Instinctively, he understood the things that he would need to do in front of a crowd, not just to get their attention but to hold it and be remembered by them…He would fake being able to summon cancers from people’s bodies, which were actually rotten chicken parts that he would have planted earlier.

And even then, as he starts to gain a following through these apparent miracles, he has a number of followers who are well aware [that] it’s a trick. But they tell themselves Jim is doing what he has to do to bring people in for the greater good, because at the same time he’s … tricking people, he’s also out there working for integration, for civil rights, for women’s rights, and that is his argument: “I need to do whatever is necessary to get people into the cause. After that we can all accomplish great things.”

If it wasn’t black magic that allowed Jim Jones to brainwash thousands of followers and lead 900 of them to their death by murder and suicide, then what was it? Cult leaders are nothing more than dark sorcerers skilled in the magical manipulation of belief.

V.

The placebo effect itself seems kind of magical—you get healing for “nothing”, a seeming violation of the TANSTAAFL principle (There Ain’t No Such Thing As A Free Lunch). The clearest explanation of the placebo effect and why it doesn’t violate the TANSTAAFL principle that I’ve seen comes from an unlikely source, Nick Bostrom (he of the simulation argument and Superintelligence). From his paper “An Evolutionary Heuristic For Human Enhancement” (highly recommended if you are at all interested in human enhancement or evolution):

While the immune system serves an essential function by protecting us from infection and cancer, it also consumes significant amounts of energy (23). Experiments have found direct energetic costs of immune activation (24). In birds immune activation corresponded to a 29 per cent rise of resting metabolic rate (25) and in humans the rate increases by 13 per cent per degree centigrade of fever (26). In addition, the protein synthesis demands of the immune system are sizeable yet prioritized, as evidenced by a 70 per cent increase in protein turnover in children during infection despite a condition of malnourishment (27). One would expect the immune system to have evolved a level of activity that strikes a tradeoff between these and other requirements—a level optimized for life in the EEA but perhaps no longer ideal. Such a tradeoff has been proposed as part of an explanation of the placebo effect (28). The placebo effect is puzzling because it apparently involves getting something (accelerated recovery from disease or injury) for nothing (merely having a belief). If the subjective experience of being treated causes a health promoting response, why are we not always responding that way? Studies have shown that it is possible chemically to modulate the placebo response down (29) or up (30).

One possible explanation is that mobilizing the placebo effect consumes resources, perhaps through activation of the immune system or other forms of physiological health investment. Also, to the extent that the placebo response reduces defensive reactions (such as pain, stiffness, and inflammation), it might increase our vulnerability to future injury and microbial assaults. If so, one might expect that natural selection would have made us such that the placebo response would be triggered by signals indicating that in the near future we will (a) recover from our current injury or disease (in which case there is no need to conserve resources to fight a drawn-out infection and less need to maintain defensive reactions), (b) have good access to nutrients (in which case, again, there is no need to conserve resources), and (c) be protected from external threats (in which case there is less need to keep resources in reserve for immediate action readiness). Consistent with this model, the evidence does indeed show that the healing system is activated not only by the expectation that we will get well soon but also by the impression that external circumstances are generally favorable. For example, social status (31), success, having somebody looking after us (32), sunshine, and regular meals might all indicate that we are in circumstances where it is optimal for the body to invest in healing and long-term health, and they do seem to prompt the body to do just that. By contrast, conflict (33), stress, anxiety, uncertainty (34), rejection, isolation, and despair appear to shift resources towards immediate readiness to face crises and away from building long-term health.

To summarize: the immune system evolved to limit the strength of its response to most immune challenges because full activation can leave the individual in a highly weakened state, something that was very dangerous in our ancestral environment.

Magical healing techniques then are those operations that can coax the immune system into releasing this latent power. In this view, shamans are a little bit more than just “cheesecake”, as proposed by Manvir Singh in his fascinating paper, “The Cultural Evolution of Shamanism”:

Previous accounts have conceived of the shaman as a charlatan, a psychotic, an inspired priest, a performer, a psychoanalyst, a guardian, and a doctor. Following this theory, I propose an addition to the list: the shaman as cheesecake. That is, the shaman as “an exquisite confection crafted to tickle the sensitive spots of our mental facilities” (Pinker 1997, p. 534). In the same way that cultural evolution and bakeries have devised sweets configured for our Stone Age sense organs, cultural evolution and ingenious performers have assembled myths and customs that hack our psychologies to placate our anxieties.

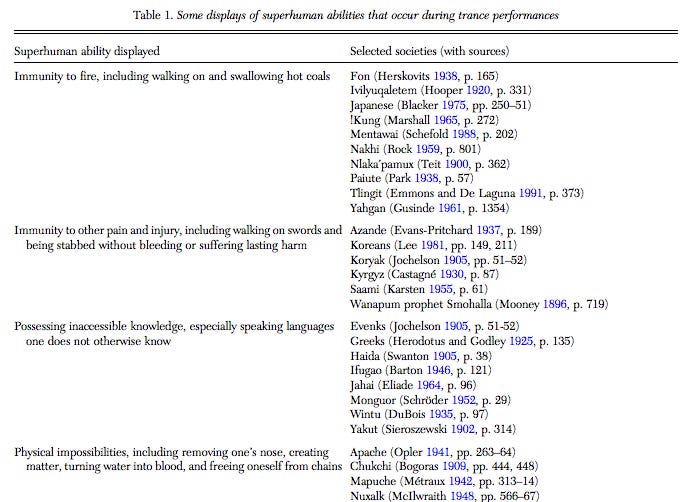

In essence, Singh argues that shamanism is a kind of cultural attractor arising from the quirks and biases of the human mind. For example, we have a tendency to attribute unpredictable outcomes (recovery from illness, weather, agricultural yields) to invisible agentic forces (gods, spirits, demons). Shamans exploit this tendency by undergoing extreme initiation rites and manifesting bizarre behavior during trance states, both of which are designed to convince others that they have a supernatural ability to communicate with these invisible forces and thereby influence the outcomes of unpredictable events.

Singh emphasizes that his theory is agnostic about whether or not the shaman is providing any true benefit to his tribe. My account would suggest that, at least in some cases, shamans are providing such a benefit (Nicholas Humphrey argues much of the same in a commentary on Singh’s article entitled, “Shamans as healers: When magical structure becomes practical function”). Perhaps then it would be more accurate to say that yes, shamans are cheesecake, but when the cheesecake is prepared by a talented chef who truly believes that his cheesecake has healing powers (and the person eating it believes the same), the cheesecake can be so good that it actually does have medicinal properties, not dissimilar to how mom’s home cooking can be good for your “soul” regardless of its nutritional value.

VI.

The model of magical healing I’ve presented here is one of extreme context-dependence—the wider psychosocial environment and the complex multi-sensory performance must be combined in just the right manner for the treatment to be successful. In this view, magical practices of this nature are inherently not amenable to scientific study—the second you put someone in a lab and have them fill out a consent form, the potential for magic has already been lost.

This is not to say that all magic is impossible in scientific environments. Indeed, experimental psychology has been unwittingly conducting magic in the lab for decades that is no less context-dependent. The scientific worldview of the experimenter and subject, the psychosocial context provided by a university, and the intricate ritual of the experiment all combine to produce the magical effect. Though I’m not aware of anyone who has framed it this way, the replication crisis then is really just the growing recognition that most of the results from experimental psychology are just radically context-dependent magical phenomenon.

This raises the prospect of explicitly engineering a form of “scientific magic” for the purpose of eliciting powerful placebo responses. Sure enough, a recent study “Super Placebos: A Feasibility Study Combining Contextual Factors to Promote Placebo Effects” has taken an important first step in this direction. Though I don’t think the authors would consider their experiment a shamanic healing ritual, I would argue that’s exactly what it is. I will quote at length from the paper in order to give the general idea of what they did, why they did it, and what they found, but please feel free to skip around once you get the gist.

“Many elaborate medical procedures are essentially placebos. Some surgical interventions for osteoarthritis (1) or Parkinson's disease (2) do not outperform sham versions of the procedures, nor do some neurological interventions such as brain stimulation for depression (3, 4) or EEG neurofeedback for ADHD (5, 6). To be clear, these procedures may still be effective, but placebo factors play a substantial role. These strong placebo effects may be partly due to the perceived complexity of the intervention. Some evidence suggests that sham procedures or medical devices that appear more complex have stronger effects (7–9); for example, sham surgeries and placebo acupuncture are generally more effective than inert pills (10). Beyond perceived complexity, numerous contextual factors modulate placebo effectiveness, including the perceived cost of the procedure (11, 12), colour of the pill (13), presence of other patients (14, 15), competence and warmth of the healthcare provider (16–18), and expectations of the patient (19). Given the importance of these contextual factors, some researchers argue that placebo effects should be reconceptualised as contextual healing with more emphasis on these various performative elements (8). Thus, placebo researcher Ted Kaptchuk (8) states that “with good showmanship, a well-designed, totally inert stage prop … can produce exaggerated placebo effects.” (emphasis mine)

Sound familiar?

As an initial test of this hypothesis, the present study combined various contextual factors in an attempt to promote placebo effects, involving a “showman” (a celebrity science communicator), a film crew, and an elaborate (but inactive) MRI scanner serving as a placebo machine. Our aim was to assess the feasibility of an intentionally elaborate intervention uniting insights from placebo science with the allure of cutting-edge neuroscience technology.

Methods

We recruited children, since they are known to be particularly susceptible to placebo effects (33). We initially targeted children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD; n=8) and Tourette Syndrome (TS; n=4, often co-morbid with ADHD), two disorders known to be receptive to placebos and positive suggestions (34, 35). During recruitment we also accepted participants who contacted us with chronic skin picking (n=1) and migraines (n=1).

An assistant wearing a white coat greeted the family, built rapport, answered questions, and then led the family to a waiting area outside the brain imaging center. After a 5-min wait to build anticipation, the family entered the MRI control room to meet the experimenters (co-authors JO and SV) and a science communicator (Michael Stevens), all dressed in lab coats to increase credibility (37). Three camera operators were also present. As in our previous study (29), the room resembled that of a cutting-edge neuroscience experiment, with scientific-looking equipment and computer screens displaying brain scans (38).

After warmly greeting the families and building rapport (which can enhance placebo effects) (16), we explained to the children that we were not medical doctors but were instead scientists who study the mind. We explained that the camera crew had flown in from Los Angeles to film our novel procedure… We then explained that the procedure involved entering “what some kids call the healing machine.” We told them the procedure works through suggestion, which we described as a “very powerful thought that can help you heal yourself.” We stated that the entire intervention—“everything that we say and do, everything you see around us, this equipment, these lab coats, as well as the machine”—is part of the suggestion procedure.

We then brought families into the adjacent scanner room containing a decommissioned 1.5 T Siemens MRI scanner. The machine appeared to be fully functional, with lights, fans, a display screen, and a sliding table. Speakers inside the scanner played pre-recorded MRI sounds on top of mystical-sounding “space music” (Floating Galaxies by Nebula). We told the children that it was a “modified brain scanner that originally was used to take pictures of the brain but now helps children heal themselves through the power of suggestion.”

Results

The procedure was feasible and no unexpected issues arose. No children or parents reported any adverse effects from the procedure, beyond temporary drowsiness after the machine sessions. Overall, ten of the eleven parents reported improvements in their children following the sessions. Two children showed near-complete cessation of symptoms. We describe the (pseudonymous) participants' improvements, approximately ordered by strength, noting that the cause of these changes cannot be determined in our feasibility study.

Limitations

This feasibility study had clear limitations. Given the design and small heterogeneous sample, we cannot make any causal claims or speculate about the generalisability of the results. Further, some of the parents' reports were likely biased by self-selection, Hawthorne effects, demand characteristics, and a desire to present well for the scientists and film crew. These biases may be less likely to explain the more easily measurable effects such as skin healing and migraine cessation, but our study was intended to test feasibility rather than effectiveness. If these improvements do represent causal effects, these results would be consistent with other studies showing positive effects in the placebo control groups of neurological interventions (3–6, 49).

This essay is already much too long so I’ll keep my comments brief.

It is interesting that the study was only conducted on children (ages 6-13). The reasons for which were not discussed in the article, but I think they are apparent enough; we can imagine that an adult participating in the experiment might have all kinds of questions like, “Hold up, why are you filming this again? Am I getting paid for this?” or “Wait you said the machine works by suggestion—what the fuck does that mean? Is this just an elaborate placebo effect?”. This form of Science Magic™ can only work on children who still possess the unreflective naive belief characteristic of an enchanted worldview.

Is it possible to create a scientific magical technique that works on adults, even someone like myself with a certain level of scientific knowledge? Perhaps in the future we will come to recognize a variant of Clarke’s Third Law; humor me, let’s call it Bacon’s Third Law: “Sufficiently advanced technologies are not just indistinguishable from magic, they are magic.”

Postscript

The scientist behind the Super Placebo study (Jay A. Olson) recently came out with a fascinating paper based on a similar paradigm.

Emulating future neurotechnology using magic (Dec, 2022) by Jay A. Olson, Mariève Cyr, Despina Z. Artenie , Thomas Strandberg, Lars Hall, Matthew L. Tompkins, Amir Raz, Petter Johansson.

“Novelist Arthur C. Clarke (2013) famously asserted that “any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic”. But the reverse can also be true: magic tricks can be made indistinguishable from advanced technology. When paired with real scientific equipment, magic techniques can create compelling illusions that allow people to experience prospective technologies firsthand. Here, we demonstrate that a magic-based paradigm may be particularly useful to emulate neurotechnologies and potentially.”

People are notoriously bad at predicting how they will feel or behave in a potential situation, so instead of asking people how they think they will feel about a future technology (non-invasive mind-reading) let’s just trick them into thinking it already exists and see how they react. Brilliant!

Abstract

Recent developments in neuroscience and artificial intelligence have allowed machines to decode mental processes with growing accuracy. Neuroethicists have speculated that perfecting these technologies may result in reactions ranging from an invasion of privacy to an increase in self-understanding. Yet, evaluating these predictions is difficult given that people are poor at forecasting their reactions. To address this, we developed a paradigm using elements of performance magic to emulate future neurotechnologies. We led 59 participants to believe that a (sham) neurotechnological machine could infer their preferences, detect their errors, and reveal their deep-seated attitudes. The machine gave participants randomly assigned positive or negative feedback about their brain’s supposed attitudes towards charity. Around 80% of participants in both groups provided rationalisations for this feedback, which shifted their attitudes in the manipulated direction but did not influence donation behaviour. Our paradigm reveals how people may respond to prospective neurotechnologies, which may inform neuroethical frameworks.

Your observation about what we have lost in our materialist drive to look under the hood and understand the mechanisms was explained beautifully. I'm not decrying that drive, only lamenting that eating from the Tree of Knowledge also means losing the Garden. Maybe Oedipus too would have been better off not knowing some things?

Thanks for publishing this. It is great. We now need all the amused skepticism and shamanic healing we can find. It is a war torn desert out there.