The Ego is the Enemy

how to innovate and win in sports and life

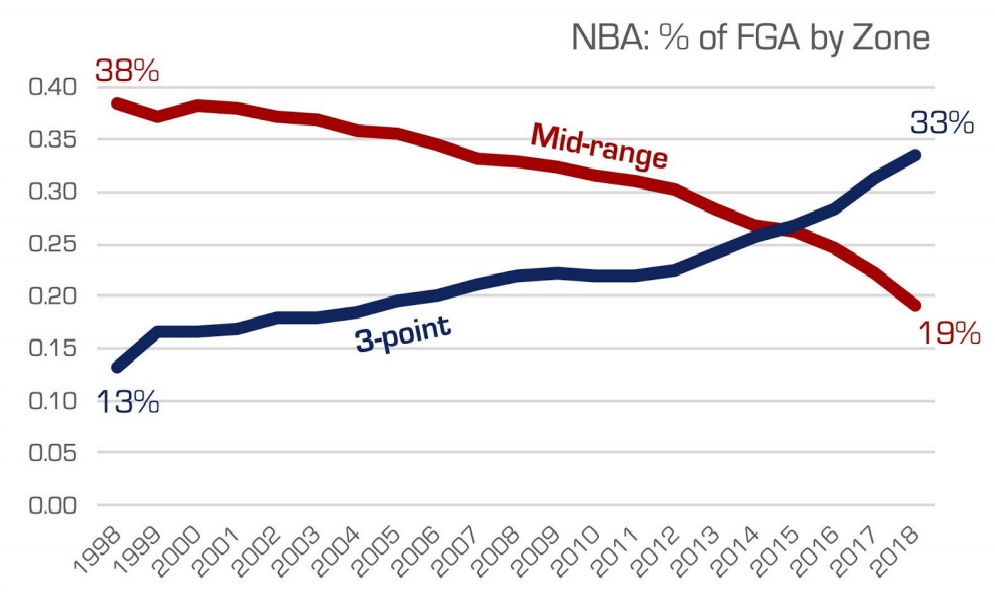

Suspended Reason calls them “adaptive ripples”, the way in which a new winning strategy spreads throughout a competitive environment. Professional basketball provides numerous recent examples, with the recent rise of 3 point shooting being perhaps the most well-known.

There were some successful teams in the 2000s (e.g. the Phoenix Suns) who found success by taking a higher percentage of their shots from behind the 3-point line, but it really wasn't until the early 2010s that everyone realized how much more valuable a 3-point shot is than a 2-point shot (who would have thought?). Daryl Morey, the then general manager of the Houston Rockets, probably gets credit for being the first to really start leaning into this strategy (shoot a shit-ton of 3s, and if you are going to shoot a 2 make sure it is as easy as possible, don’t take mid-rangers that are almost as hard as a 3 but not worth the extra point) but Stephen Curry and the Golden State Warriors utilized it to the greatest success, winning 4 of the 7 last championships by being the best 3-point shooting team of all time (while also having a top defense).

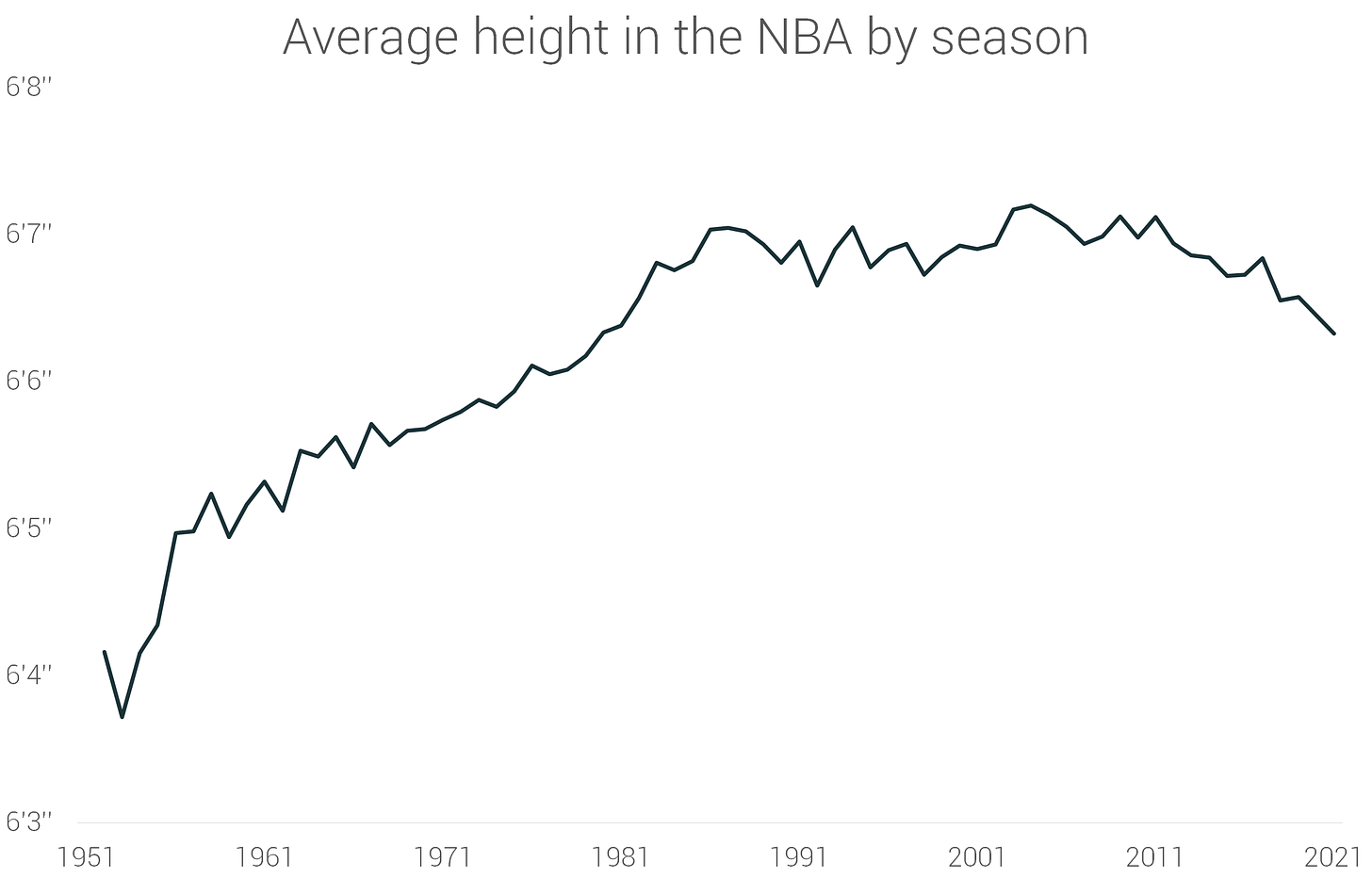

Another adaptive ripple related to the 3-point revolution is the discovery that bigger players are overvalued (6’10 and over) and “wings” (6’5-6’9) are undervalued. It turns out that it’s really difficult to play against an entire team of 6’7 freak athletes who can shoot well and are big enough to guard bigger guys adequately while also being really good at guarding players who are smaller than them (e.g. Lebron James, Kawhi Leonard).

Around 2010 we start to see a dip in the average height and weight of an NBA player.

Suspended Reason asks:

What are some of the factors that prevent basketball players from incorporating discovered winning solutions?

(1) Indexicality of play. Players might wonder: will that move or style work for my body type, my skill-set, and within my team’s context? Any given imitable element works—fits—within a complex array of other interlocking parts, which in conjunction determine efficacy. Not every player can imitate every trending technique. Not every player can equally stop any overpowered technique.

(2) Hubris. Great players are also often the most arrogant of players, a result of—and a cause of—their success. (Jane Austen is a chronicler of hubris as a general pitfall of the clever, though we can get it with Shiv on HBO’s Succession as well.) Perpetually reinventing oneself, and looking to other players’ for new moves, requires some humility. Adopting new techniques often requires crossing a fitness valley of diminishing efficacy, players will give up on adapting prematurely, or alternatively, are not easily convinced that the play style would improve their game. There is, of course, no way to easily test or demonstrate that it does, one way or the other—it requires a leap of faith.

There is an interesting tension surrounding hubris, or ego, in sports (or any competitive domain). If you are a great athlete you will of course have some level of ego as you've basically been winning at everything your entire life, and to some degree this is a good thing—confidence matters—but it can also be your downfall if taken too far, the thing that prevents you from adapting your style of play or developing a new skill (not to mention how too much ego can make you a bad teammate or selfish player).

This suggests a new meta-strategy that sports teams can use to find new winning strategies/inefficiencies: do the thing that other teams/players are not doing because of their egos, the thing they aren’t doing because every player wants to be the star of the team, because you won’t look cool doing it, because you’ll face a lot of public criticism if it doesn’t work, etc. etc.

I have a few examples of “ego inefficiencies” but first, two notes: (1) I know this might be annoying to more sports-fluent readers, but I'll try to give enough background so that people who aren't familiar with the sports can understand what I'm talking about (because this article isn’t really about sports, it’s about how you can find winning strategies if you are capable of controlling your ego), and (2) all of my examples will be from the NFL (American football) and the NBA (professional basketball) as these are the sports I'm most familiar with (would love to hear some examples/ideas from soccer and other sports).

The Granny Shot

Shaquille O'Neal is not the greatest basketball player of all time, but he might have been the most athletically dominant.

He did have one fatal flaw however: free-throw shooting (you get 2 free shots worth 1 pt each after the other team fouls you). At a certain point, teams realized that if Shaq shoots 50% on his free throws then he will get an average of 1 point every time you foul him which is less than the than the ~1.2+ points he will probably score on average if you just try to guard him without fouling. So in crucial late game situations, teams just started fouling Shaq and making him shoot free throws, the so-called Hack-a-Shaq strategy. If the player you are fouling is bad enough at shooting free throws, then it's a winning strategy.

Don Nelson initially used the strategy against Dennis Rodman, a star power forward for the Detroit Pistons, San Antonio Spurs, and Chicago Bulls. However, the strategy acquired its name for Nelson's subsequent use of it against Hall of Fame center Shaquille O'Neal.

The term was coined when O'Neal played at LSU and during his NBA tenure with the Orlando Magic. At that time, the term referred simply to play especially physical defense against O'Neal. Teams sometimes defended him by bumping, striking or pushing him after he received the ball to deny him an easy layup or slam dunk. Because of O'Neal's poor free throw shooting, teams did not fear the consequences of committing personal fouls. However, once Nelson's intentional off-the-ball fouling strategy became prevalent, the term Hack-a-Shaq was applied to this new tactic, and the original usage was largely forgotten. (Wikipedia)

By now it's common enough that coaches will not get criticized for it, but it definitely took some guts to be the first to implement the Hack-a-Shaq; it just looks bad if you do it and lose, you seem weak because you are basically admitting that you couldn’t stop the other team and that your only option was to give them a bunch of free shots and just hope they miss, which apparently they didn’t do if you lost the game. It's not a coincidence that the first coach to do it is kind of an eccentric guy (relative to most professional basketball coaches at least).

It's not that Nelson had a huge ego (though he probably did), it’s that his ego was strong enough to tolerate the initial backlash (or alternatively just be weird enough that your ego cares about different things than most other people’s). So one way we can think about this meta-strategy is: look for the thing that people would be doing if they didn’t care about being criticized.

Shaq did have a counter move available to him, one that he chose not to use, essentially just because he wouldn't have looked cool if he did it and looking cool is really important to basketball players.

Almost all basketball players shoot an overhand shot like Shaq, but Rick Barry, one of the greatest shooters ever, shot his free throws (not his regular shots) with an underhand shot, pejoratively known as “the granny shot” (don’t ask me why). Coaches told Shaquille he should shoot the underhand shot, saying that it would make him a better free-throw shooter and render the Hack-a-Shaq strategy ineffective, but he steadfastly refused (Rick Barry even offered to teach him how to do it at one point).

Shaq's LSU coach Dale Brown was the first person to try to get him to shoot underhand. One day, during O'Neal's freshman year, he came up to him and said, "You know what I’m going to do? I’m going to get you to shoot underhand. Rick Barry, who is in the Hall of Fame, was the best at it.”

Shaq hated the idea. He begged the coach to allow him to keep his original free-throw shooting technique. In his mind, the embarrassment of embracing the granny shot wasn't worth the potential improvement — especially since his father, who O'Neal looked up to his whole life, already stated his opinion on the matter years ago.

I really didn’t want to shoot them that way. When I was a kid, someone else suggested that approach before and Sarge told me to forget it. 'That’s a shot for sissies,' my father told me.

("That's a shot for sissies" - why Shaquille O'Neal never shot underhanded FTs)

So Shaq’s fragile ego (which is obvious when you see his interactions on TV as an analyst, he acts like an insecure bully) prevented him from working on a new technique that would have made him more unstoppable than he already was.

Business Insider: But it’s been proven to be somewhat effective.

O’Neal: No, it’s not. It’s not proven. Just ’cause a couple guys did it doesn’t mean anybody can do it.

I told Rick Barry I’d rather shoot 0% than shoot underhand. I’m too cool for that.

He could be right of course, but not giving it a try at least comes down to ego. The granny shot is rarely seen in the NBA (the last time someone busted it out was in 2016) even though there are always a few players in the league who are so bad at free throws that they could really benefit from even a small bump in their percentage.

Scary Hairy

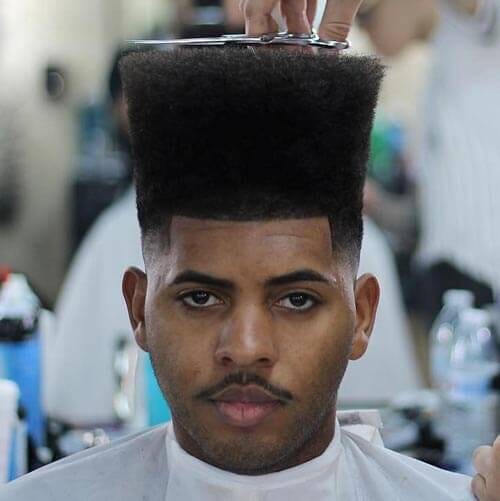

Ziaire Williams is 6’9 without hair but probably looks a solid 7’ with it. Wingspan is more important for playing defense in basketball (you are commonly raising your hands to block a shot or tip a pass) but the height of your head matters too—a few more inches in head height can be that extra bit of deterrence that makes a player miss his shot or decide not to shoot in the first place (it’s like how some mammals puff out their fur when they are scared to make themselves look larger).

When I am an NBA coach, I will tell all of my players to grow their hair out as large as possible and we will become the greatest defensive team in the history of basketball (or our opponents will shoot like 2% worse, but hey that could still make the difference between winning and losing). My players will of course look at me like I'm crazy and refuse to do it. I guess there are probably legitimate reasons for not wanting to wear an afro or an even cooler haircut like the one below, but at some level it boils down to ego and wanting to look cool—it’s lame to wear some silly haircut that your coach told you to wear, and even lamer if all of your teammates have the same one.

Look at the difference, Ziaire doesn’t seem nearly as intimidating without an afro (obviously if he had one he would have stolen the ball already).

Changes in hairstyle could also be utilized for an element of surprise—e.g. players have their hair in braids for the first half, but then go afro in the second half (or go the opposite way and have everyone get their afro cut at halftime). The other team will never see it coming!!!

Get Tricky With It

There is a famous play in basketball called “the barking dog”—at a crucial moment, have one of your players get on all fours and start barking, then take advantage of the diversion and score an easy bucket.

It's completely absurd, childish, and ridiculous, but it also works. To my knowledge, the barking dog has never been tried in an NBA game, and I can only assume the reason is that players and coaches have too much of an ego to try something so silly.

So to all the NBA players and coaches reading this (no doubt there are many):

DO IT, YOU COWARDS.

There are equally ridiculous trick plays in American football but there also many trick plays (e.g. the flea-flicker) that do totally normal things, but are unconventional either because they are a little more intricate than the typical play or they have a player doing something he doesn’t usually do (e.g. having your “running back” throw the ball). I've always been convinced that coaches don't call enough trick plays—if right now they call them on something like 1-5% of their plays, my feeling is that it should be at least double that. At least one analysis seems to agree with me:

Of course, if a team fakes punts all the time then defenses will adjust and the EPA (expected points added) will go down. The appropriate criticism here is that the novelty of the play is what makes them valuable. Still, my data analysis suggests that teams should definitely run more reverses and fake punts.

On a different note, I would argue that risk tolerance isn’t a good reason to avoid faking kicks or running reverses. Here’s an analogy. In blackjack, it feels uncomfortable to hit on 16. You frequently bust and feel stupid. However, it’s almost always the mathematically best play because the dealer will often beat 16. Often you’re simply giving the house extra edge when you stay on 16.

Like with hitting on 16, faking a punt on your own side of the field and failing probably feels stupid. However, it’s mathematically advantageous. There’s plenty of room to try it more than 1% of the time.

Note the parallel to the Hack-a-Shaq; like trick plays in football, it’s a strategy that makes the coach and players look stupid/weak if it doesn’t work (but if it works then no one cares).

The Cerberus Offense

Lamar Jackson is the quarterback of my favorite football team (the person who throws the ball), the Baltimore Ravens. Aside from trick plays where a running back or a wide receiver (specialized for catching) throws the ball, the the quarterback is always the player who throws the ball, however the quarterback can also run the ball. Lamar Jackson is a decent-to-good thrower of the ball, but maybe the best running quarterback of all time (one of his best highlights).

Traditionally, quarterbacks are highly specialized for throwing with many of the best at the position being very slow and only running as a last resort (e.g. Tom Brady, Peyton Manning). The NFL is going through something of an adaptive ripple right now as teams are starting to realize that having a quarterback who's really fast is incredibly valuable (again, who would have thought, it's not like the whole point of the sport is to run away from the defenders and avoid getting tackled). I want to take it one step further: quarterbacks should also start catching the ball.

Right now, every play starts by giving the ball to the quarterback, the player who almost certainly (aside from the rare trick play) will be the one to throw it if the team decides to do a passing play. Plays can be surprising in various ways, but there is a fundamental predictability in that the the quarterback is almost definitely the one who will pass it.

But it doesn't have to be that way.

I call it the “Cerberus Offense” because it requires you to have at least three players on the field who are a triple threat to run, pass, or catch.

In Greek mythology, Cerberus , often referred to as the hound of Hades, is a multi-headed dog that guards the gates of the Underworld to prevent the dead from leaving. He was the offspring of the monsters Echidna (a monster, half-woman and half-snake, who lived alone in a cave) and Typhon, and was usually described as having three heads, a serpent for a tail, and snakes protruding from multiple parts of his body.

The Cerberus Offense™ will be unpredictable on a completely new level, allowing for new types of plays that teams don’t even attempt now because they are locked into the single quarterback paradigm. I am 110% certain that the Cerberus Offense™ will be completely unstoppable if implemented properly—defenses will be so utterly bamboozled and discombobulated that they won’t know left from right (and if doesn’t work then it’s because it wasn’t implemented properly).

One obvious counter-argument is that it will be really hard to find players who can do all three things at a high-level. I'm just not buying that; Lamar Jackson is a freak athlete who has been good at every sport he’s played his entire life, I’m sure with a little practice he will be able to catch the ball just fine. Also, many people who go on to become wide receivers or running backs in the NFL have played quarterback at lower levels (some in college) and should be able to throw the ball well enough to make it a weapon with the right preparation. I'm also not saying that all of your players need to be a triple threat (only three of them, you could still have three wide receivers on the field), or that every member of the three-headed monster has to be equally good at throwing—I want to see something like 17, 7, and 5 passing attempts respectively for the Cerberus players, just enough to keep the defense guessing about who will throw the ball on any given play. The one counter-argument I will give some credence to is that distributing your passing attempts like this would make it hard for your Cerberus players to “get in a rhythm” (gain confidence by completing a few passes in a row, get used to the ball and weather conditions, etc.). So yeah sure maybe “rhythm” does matter a little bit, but also you are getting paid millions of dollars to throw an oblong leather ball, just figure that shit out and make it happen.

If I was coach of the Baltimore Ravens I would say to Lamar, “look, I know you are going to think this is crazy, but we want to start using you as a receiver too. We are going to draft/sign two other quarterbacks and also have them throw/run/catch. The complexity and unpredictability of this offense will be like nothing anyone has ever seen before and you will go down in history for revolutionizing the game of football.” Lamar would reply, “that's the dumbest shit I've ever heard and I hate you, please trade me right now”. Now on one hand, this is completely rational from his perspective—football is his career and he wants to be a star quarterback because those are the highest paid players. Sure winning is important and all, but why would he want to be just one of three quarterbacks on his team and make less money because of it? On the other hand, there is also a part of Lamar’s hypothetical refusal that would be driven by ego, by him wanting all the attention that comes from being the quarterback (QB is the most glamorous position in the sport, they are usually the leader of the team, get the most attention in the media, etc.)

(I’m kind of joking with the Cerberus name, but it does raise an important point. Names matter—if you are asking someone to set aside their ego in a big way, then at least try to make it sound cool. Framing matters too—if I was actually trying to pitch this to the Ravens coaches and Lamar Jackson (just give me one chance…), I would really play up the revolutionary nature of the strategy, how they could go down in history for changing the way the sports is played, stuff like that.)

(I’ve been told that the Cerberus offense is basically the same as the Single-Wing Offense, which was common in the early days of football but has since fallen out of favor. I do admit that there are some superficial similarities between the two offensive systems, however any similarities are just that—superficial. The Cerberus Offense is superior because it has a cooler name, and the name is essential to the the mindset of the players and the overall ethos of the football team and—i.e. a team that runs the Cerberus could run the same plays as a Single Wing team but they would not be the same team.)

The Ego is the Enemy

Implementing the Cerberus Offense™ might require you to find three Lamar Jackson's that are also Buddhist monks; I will concede that this does seem to be a fairly difficult task. Even still, I think the Cerberus Offense™ is a good example of the kind of thing that a team might attempt while employing the anti-ego meta-strategy. Aside from any specific inefficiency, I would suggest that teams are generally under-appreciating the corrosivity of ego and that they should make the control of their player’s egos a much higher priority. I’m watching the show “Hard Knocks” right now, a documentary show that follows one NFL team as they prepare for the season. The mantra of the team in the show, The Detroit Lions, is “Grit” (painted in giant letters all over the walls in their training facility); it would be better if it was “The Ego is the Enemy”.

I’m borrowing the phrase from a book of the same name by Ryan Holiday which has some great quotes on ego and its role in failure and success (emphasis mine).

Most of us aren’t “egomaniacs”, but ego is at the root of almost every conceivable problem and obstacle, from why we can't win to why we need to win all the time and at the expense of others. From why we don't have what we want to why having what we want doesn't seem to make us feel any better.

If ego is the voice that tells us we're better than we really are, we can say ego inhibits true success by preventing a direct and honest connection to the world around us. One of the early members of Alcoholics Anonymous defined ego as "a conscious separation from." From what? Everything.

The ways this separation manifests itself negatively are immense: We can't work with other people if we've put up walls. We can't improve the world if we don't understand it or ourselves. We can't take or receive feedback if we are incapable of or uninterested in hearing from outside sources. We can't recognize opportunities—or create them—if instead of seeing what is in front of us, we live inside our own fantasy. Without an accurate accounting of our own abilities compared to others, what we have is not confidence but delusion. How are we supposed to reach, motivate, or lead other people if we can't relate to their needs—because we've lost touch with our own?

Phil Jackson, coach of the Michael Jordan Bulls dynasty and the Kobe/Shaq Lakers dynasty, definitely appreciated how detrimental big egos could be to a team and was successful in part because he was good at helping his star players control their egos.

“The best way to control people is to give them a lot of room and encourage them to be mischievous, then watch them. To ignore them is no good: that is the worst policy. The second worst is trying to control them.”

“After years of experimenting, I discovered that the more I tried to exert power directly, the less powerful I became. I learned to dial back my ego and distribute power as widely as possible without surrendering final authority.”

—Phil Jackson

Jackson would do all kinds of unorthodox things—give his players books to read (he gave Shaq Herman Hesse’s Siddhartha and asked him to write a book report on it), teach them meditation techniques, or turn the lights off during team meetings for no reason ("It wasn't totally dark, but I wanted them to get the idea of being able to do things that are just out of the ordinary, like silence day—have a day of just silence."). He would also talk a lot about love, telling his players that they had to truly love each in order reach their full potential (“Love is the force that ignites the spirit and binds teams together”, from his book Sacred Hoops).

Jackson won 11 championships in total, but it could've been a few less if he coached in a more conventional manner (and it could've been a few more if he was a little better at managing egos). He won his first six with Michael Jordan as the star player. In game 6 of the NBA finals with the championship on the line (the Bulls had won the previous two championships), Jordan passed the ball out to John Paxson who hit the game winning shot. Jordan was known for taking (and usually making) the biggest shot of the game, so it was especially surprising to see him pass in this situation, a testament to Jackson’s work on Jordan’s mindset.

“That is something I’ve learned from Phil. Calming the body,” Jordan told ESPN in April 1998. “No matter how much pressure there is in a game, I think to myself: It’s still just a game. I don’t meditate, but I know what he’s getting at. He’s teaching about peacefulness and living in the moment, but not losing the aggressive attitude. Not being reckless, but strategic. What I do is I challenge myself in big games. I try to find a quiet center within me because there’s so much hype out there, and I don’t want to fall into it. I don’t want to rush. I’ll start off rebounding or getting everybody else involved until I get an easy shot, a layup, or a free throw or something, then boom, I’m off and running. I will have controlled my emotions and not gotten over-hyped or lost my focus. These are things Phil has taught me. And I’ll tell you, it all works, in big games more so than anything.” (source)

Jackson won his next three championships with Kobe and Shaq as the star players. They won three in a row from 2000-2003, but then eventually the team had to trade Shaq because him and Kobe couldn’t set their differences and their egos aside. They had all kinds of issues with each other, but really it just boiled down to the fact that they both wanted to be the biggest star on the team. It would be too strong to call this a failure on the part of Jackson, but if he had somehow been able to get Shaq and Kobe to check their egos and stay together it’s not unreasonable to think that they could've won another three championships.

Jackson won his last two championships with only Kobe as the star player. Kobe was a lot like Jordan, but if anything he had an even bigger ego. The Boston Celtics, the Lakers opponent in the 2010 finals, knew this about Kobe and tried to use it against him. The Celtics’ defensive plan for the final game was to double team Kobe and force him into tough shots, knowing that Kobe would not want to pass because he would want to be the leading scorer and win the MVP award (I can't find a source for this, but I've heard Bill Simmons talk about this multiple times). It worked perfectly—Kobe shot 6/24 (way below his usual percentage)—but the Lakers won off a last second shot by Metta World Peace (the artist formerly known as Ron Artest…he’s quite the character).

We probably still don't appreciate Phil Jackson's approach enough because it's easy to discredit his success given that he coached some of the greatest players ever. If I owned a sports franchise, I would really try to lean into egolessness as one of our foundational principles in the same way that Jackson did. Although I might want to have my team try the Cerberus Offense™ or the all-afro strategy, it would be egotistical of me to push all of my ideas on coaches and players who know way more about football/basketball than I ever will. This does happen all the time though, so frequently in fact that it’s been given a name: New Owner Syndrome—the billionaire businessman with a huge ego buys a team and starts making all kinds of big splashy changes (e.g. hiring a new coach, trading for a star player), most of which turn out poorly in the end.

So the first thing I would do in order to implement this meta-strategy is master my own ego (good luck, buddy) and accept that it's probably better if I take a backseat and don't get too involved with the coaches or the players. The second thing I would do is hire an actual Zen Master as my coach, instead of a fake one like Phil Jackson. Again, I am willing to concede that it may be difficult to find a Zen Master qualified to coach an NBA/NFL team; if I can’t find a ZM/coach then I will find people with expertise in controlling egos (ZMs or otherwise) and introduce them to my team (only if they are open to it) just to see if any lasting influence or relationship develops.

I would also do what I could, on the margins, to create a culture of love amongst my coaches and athletes. In a sports world that incentivizes arrogance, there will be inefficiencies which can only be exploited if you can learn to control your ego (and indeed many of the greatest basketball players ever have been incredibly selfless people—e.g. Bill Russell, Tim Duncan, Steph Curry). Similarly, in a sports world dominated by toughness and masculinity, love will be an underutilized strategy, only available to those who are capable of giving and receiving it.

The barking dog play should 100% happen

I think the armchair psychology here is backwards. The biggest egomaniacs - eg Michael Jordan and LeBron James, let’s say - are the most likely to adapt because adapting is what allows them to keep winning. Both players adapted their style of play at a later age - MJ with turnaround jumpers, LBJ with more three pointers - because they could not excel playing the same way as they did when they were both the athletic peaks of the league.