Nomen est omen

On nominative determinism and the power of names

I.

An aptronym is when a person has a name that is uniquely suited to its owner. Some examples:

Usain Bolt, the fastest human ever

Mark De Man, Belgian football defender

William Headline, Washington Bureau Chief for CNN

Marijuana Pepsi Vandyck, American education professional with a dissertation on uncommon African-American names in the classroom

William Wordsworth, poet

Philander Rodman, father of basketball player Dennis Rodman, who fathered 26 children by 16 mothers

Sue Yoo, attorney

And of course there are also inaptronyms:

Rob Banks, a British police officer

Don Black, white supremacist

Robin Mahfood, President and CEO of Food for the Poor

I.C. Notting, an ophthalmologist at Leiden University

Maybe this is all coincidence, or maybe it’s nominative determinism, the hypothesis that people that people tend to gravitate towards areas of work that fit their names (an idea captured in the ancient Roman proverb “nomen est omen” meaning “the name is the sign”). Psychologist Lawrence Casler proposed three possible explanations for nominative determinism: one's self-image and self-expectation being internally influenced by one's name; the name acting as a social stimulus, creating expectations in others that are then communicated to the individual; and genetics—attributes suited to a particular career being passed down the generations alongside the appropriate occupational surname.

But does nominative determinism actually exist—are people with occupation-related names over-represented in those occupations? After an extensive review of the literature (lol jk I just read the wikipedia page), my conclusion is: eh, I guess so? Some studies have found a fairly strong effect but these have been criticized for failing to properly account for confounds; other (slightly) more rigorous studies seem to find weak effects and some analyses show no effect at all. So basically it’s just like any other psychological theory that we’ve turned a more critical eye to in recent years.

This section from the wikipedia page had me rolling in laughter.

In 2015 researchers Limb, Limb, Limb and Limb published a paper on their study into the effect of surnames on medical specialisation. They looked at 313,445 entries in the medical register from the General Medical Council, and identified surnames that were apt for the speciality, for example, Limb for an orthopaedic surgeon, and Doctor for medicine in general. They found that the frequency of names relevant to medicine and to subspecialties was much greater than expected by chance. Specialties that had the largest proportion of names specifically relevant to that specialty were those for which the English language has provided a wide range of alternative terms for the same anatomical parts (or functions thereof). Specifically, these were genitourinary medicine (e.g., Hardwick and Woodcock) and urology (e.g., Burns, Cox, Ball). Neurologists had names relevant to medicine in general, but far fewer had names directly relevant to their specialty (1 in every 302). Limb, Limb, Limb and Limb did not report on looking for any confounding variables. In 2010 Abel came to a similar conclusion. In one study he compared doctors and lawyers whose first or last names began with three-letter combinations representative of their professions, for example, "doc", "law", and likewise found a significant relationship between name and profession. Abel also found that the initial letters of physicians' last names were significantly related to their subspecialty. For example, Raymonds were more likely to be radiologists than dermatologists.

This kind of blew my mind—there is actually some evidence for the genetic explanation (i.e. attributes suited to a particular career being passed down the generations alongside the appropriate occupational surname).

As for Casler's third possible explanation for nominative determinism, genetics, researchers Voracek, Rieder, Stieger, and Swami found some evidence for it in 2015. They reported that today's Smiths still tend to have the physical capabilities of their ancestors who were smiths. People called Smith reported above-average aptitude for strength-related activities. A similar aptitude for dexterity-related activities among people with the surname Tailor, or equivalent spellings thereof, was found, but it was not statistically significant. In the researchers' view a genetic-social hypothesis appears more viable than the hypothesis of implicit egotism effects.

II.

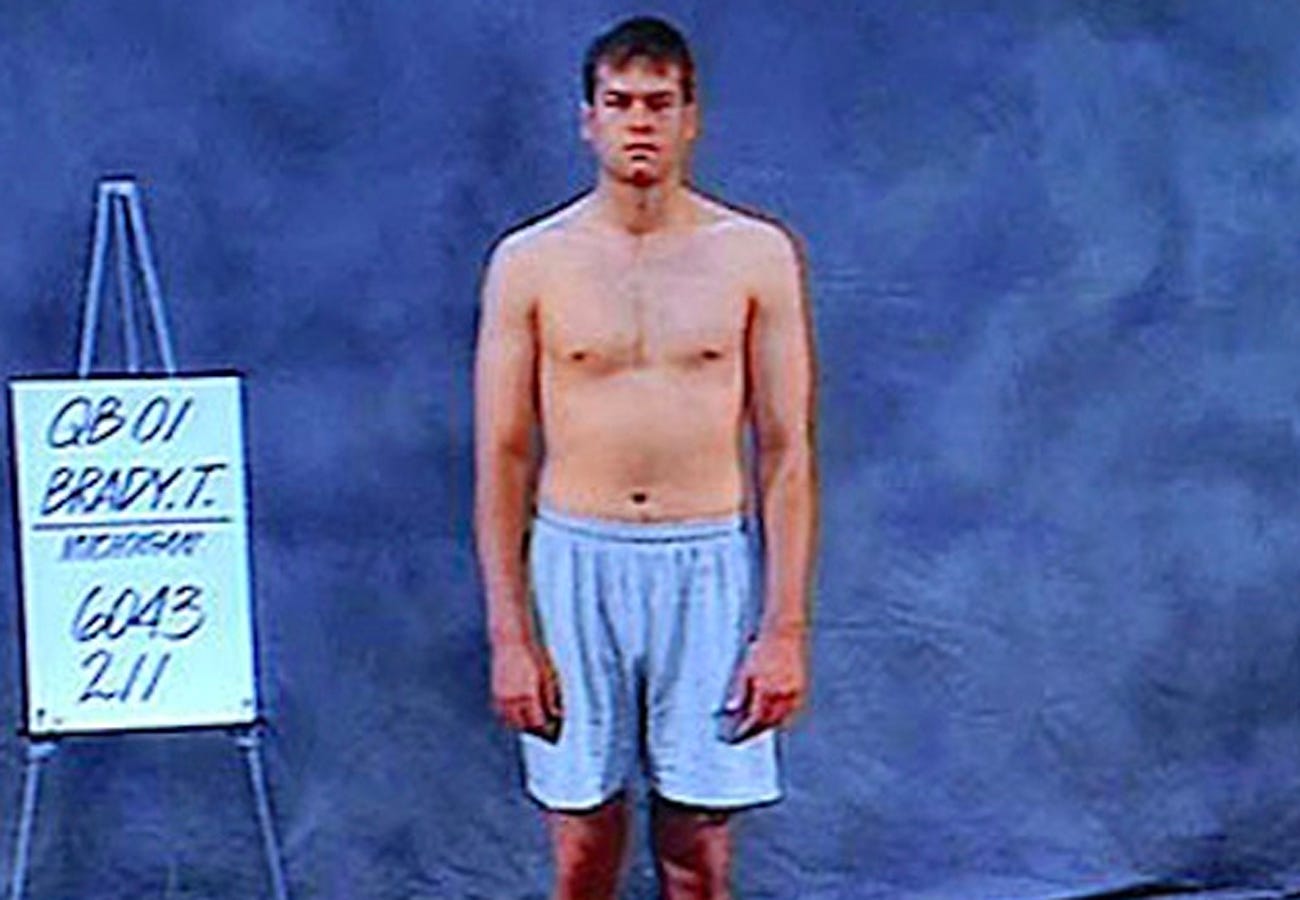

Nominative determinism is about how someone’s name can influence their choice of a career. What’s more interesting to me is something like the reverse of this—how a name can influence the way someone is perceived and treated by others, perhaps giving the person a small advantage that increases their chances of success (or a disadvantage that increases their chances of failure). I’ve had this pet theory for a while that names are super important for an athlete, that a great name can become a self-fulfilling prophecy which can propel its owner to stardom. Cristiano Ronaldo, Peyton Manning, Lebron James, Lionel Messi, Tom Brady, Kobe Bryant—I’ve always felt like the best athletes usually have strong, catchy names and that this has somehow played a role in their greatness. Sure, this might just be hindsight bias, but hear me out—I think there is a plausible mechanism for how this might work.

You might have heard of the Bouba-Kiki effect, recently popularized by this meme. Quick, without thinking—which one of these figures is kiki and which is bouba?

If you are like ~95% of people then you thought the left image was kiki and the right was bouba.

The bouba/kiki effect is a non-arbitrary mapping between speech sounds and the visual shape of objects. It was first documented by Wolfgang Köhler in 1929 using nonsense words. The effect has been observed in American university students, Tamil speakers in India, young children, and infants, and has also been shown to occur with familiar names. It is absent in individuals who are congenitally blind and reduced in autistic children.

Ramachandran and Hubbard suggest that the kiki/bouba effect has implications for the evolution of language, because it suggests that the naming of objects is not completely arbitrary. The rounded shape may most commonly be named "bouba" because the mouth makes a more rounded shape to produce that sound while a more taut, angular mouth shape is needed to make the sounds in "kiki"

I bring this up as an example of how the raw sonic qualities of a name can bring to mind certain abstract associations. The name Tom Brady just sounds more powerful than Blake Bortles (a top quarterback prospect who flopped—I totally predicted that he was going to suck). There is a pleasant lyricality to the name Cristiano Ronaldo, it just sounds like the name of person who would be famous. Lionel Messi also sounds like it would be the name a legendary athlete—Lionel calls to mind lions, the so-called king of the jungle, and the name Messi sounds like it could be the name of famous artist, like Dalí or Da Vinci.

So what is the actual mechanism whereby a great name leads to athletic greatness? Say you are 8 year old Tom Brady (or Cristiano Ronaldo or whoever) playing on your first (american) football team. The coach, just some random dude who coaches youth football, doesn’t really have any sense of the athletic abilities or personalities of his players at first. They have a few practices and the coach slowly starts to get a sense of who’s good and who’s not. Maybe young Tom Brady seems like he’s one of the best athletes, but there are other kids who are bigger or faster (Brady certainly didn’t become the winningest quarterback of all time because he was a freak athlete). Eventually you have to choose a quarterback, the most important player and natural leader of the team (for those who aren’t familiar with the sport), and you go with your gut and choose that Tom Brady kid—you don’t really know why, he just seems confident, a good-looking kid who has a natural charisma about him (basketball hall-of-famer Charles Barkley, also the owner of great name, has said about Brady, “I made a mistake. I looked Tom Brady in the eyes. I'm looking at these guys and Tom Brady is right here and I look him in the eyes and I say ‘damn you a pretty man’ ”). I’m giving a fictional example here obviously but this is basically my experience with coaching youth sports of varying ages (mainly high school) for 6+ years—there are just certain kids that you like and want to see succeed for reasons that you can’t really articulate. You really don’t have a lot to go on at first when choosing the point guard/striker/team captain/etc. so you end up going with your gut and choosing the kid that seems like he has the “it” factor.

So young Tom Brady gets a little boost of confidence from being chosen to play quarterback. This sets in motion a snowballing Matthew effect (“the rich get richer”) that has a not-insignificant impact on his athletic destiny. Many youth programs carry the same group of kids up through the age groups, so once young Tom Brady does well at quarterback in his first year he is almost certainly going to play the position and be the leader of the team going forward. His early success has all kinds of knock-on effects that feedback on themselves in a virtuous loop—his coaches give him more attention and encouragement, this motivates young Tom to work even harder, his parents see all of this and invest more time/money/attention into his budding football career, and so on and so forth.

So then we have 18-year old Tom Brady who has been a leader and a winner his entire life. Not only does this provide all of the aforementioned psychological benefits, it also changes him physically.

In many animal societies, a high dominance rank is beneficial (1, 2). High-ranking primates, for example, tend to experience higher reproductive success and/or greater offspring quality as measured by survival, growth rates, and accelerated maturation (3–8). Social rank also influences health (9). (source)

Being the alpha male monkey in his peer group (which for young boys is not a far-cry from a chimpanzee society) means that young Tom has a lifetime of elevated testosterone levels (both a cause and consequence of having a high dominance rank), that he hits puberty earlier (which just cements his dominant status even further), and receives a whole host of other physiological benefits that help him grow to be stronger and more athletically skilled than he would have otherwise been.

This was all incredibly painful for me to write because I actually hate Tom Brady (sports hate not real hate) as my favorite team (the Baltimore Ravens) was rivals with Brady’s New England Patriots teams. I chose to use him as the example because (1) american football felt like the best sport to use because of the unique nature of the quarterback position and (2) the other person I would’ve used, Peyton Manning (who was actually better than Tom Brady but just had worse coaches/teams during his career—fight me), had a dad (Archie) who was also a hall-of-fame quarterback so he was already marked for greatness for reasons other than having a good name. On the other hand, maybe I should have gone with the Manning example and avoided the whole vomit-inducing exercise of having to write positive things about Tom Brady because it might illustrate my point on an even deeper level—this snowballing Matthew effect can even be intergenerational. Everything I said about young Tom probably holds even more so for young Archie (born in 1949) as he was playing youth football at a time when much less money/attention was devoted to identifying and cultivating athletic talent, thus making it even more likely that a random superficial factor could change a young athlete’s trajectory. So Archie Manning, aided in some small part by his strong surname, becomes a rich and famous Super Bowl-winning quarterback and then goes on to have not 1 but 2 sons, Peyton and his little brother Eli (not as great as Peyton, but also a two-time Super Bowl-winning quarterback), who also become all-time greats because they are born with every possible advantage one could want for an aspiring quarterback. And it hasn’t stopped there—now Peyton and Eli’s nephew Arch is also a top high school quarterback prospect.

III.

There is of course no reason why this naming effect would only be limited to athletics. Philosophy Bear has a really interesting idea called writerly bias that feels relevant here (h/t to friend of the blog Brad & Butter for sharing this).

Only important intellectuals and artists write or create works on the human condition that are well remembered, but most people are neither important artists or intellectuals, thus we should expect cultural understandings of the human condition to be jaundiced with the perspective of artists and intellectuals.

I call this the writerly bias - the literature is, unavoidably, stacked towards writers, but we understand ourselves through this tradition, ergo, their is an inescapable flaw in the way we see ourselves.

I see the writerly bias as linked to other biases. For example, the narrative bias:

Our understanding of what it is like to be human, and how lives generally unfold, will be stacked towards forms of experience that can be placed into coherent narratives, because this is what is mostly to get written (and even spoken!) about.

Anyone who has ever caught themselves analyzing their own life in terms of literary tropes, even for a moment, or feels surprised that something which felt like foreshadowing never eventuates, knows what narrative bias is like.

All very fascinating, but I wonder if writerly bias applies beyond just our understanding of the human condition but to human history itself. Yes, history is written by the victors, but it’s also written by the writers (duh); in other words, people who are good writers, who for whatever reason are good at coming up with highly virulent memes—easily remembered terms, catchy slogans, witty quips, inspirational mottos, powerful or well-fitting names—will have an outsize impact on the the course of history. This memetic ability will correlate strongly with verbal and social intelligence, but not completely—some people just have an ineffable knack for coining terms or naming things (today we might call this being good at twitter).

How many movements, philosophies, religions, or empires have risen or fallen because of the memetic contagiousness of their name? How much has the flow of history been altered by a good name at the right place and the right time, or a bad name at the wrong place and the wrong time?

Probably not that much, but also probably more than you might think.

IV.

In 20 Modern Heresies, I wrote/quote the following:

“15. The virtually universal practice of assigning a permanent name at birth (which only exists so that governments can more easily tax us) has caused a species-wide shift towards a more narcissistic and egotistical mode of being.

“In these preconquest regions of New Guinea names were rarely binding. What one was called varied according to time, place, mood, and setting. Names were improvised, not formally bestowed, and naming (much like local language flexibility) was often a kind of humorous exploratory play. New names could be quickly coined, often whimsically from events and situations, with a new one coming up at any time. One young boy running in a peculiar way was affectionately dubbed 'Grasshopper': It stuck. Another was called 'Kaba' (short for the prized embokaba beetle) because, during an episode of biting-mouthing play, a friend proclaimed his skin was as delicious as that savory beetle's flesh. One girl was called 'Aidpost' following her excitement about the first one in the region; another was called 'Sleepgood' by a new friend who liked sleeping with her. A boy from a distant hamlet in the south who tagged along when I went north to the new Australian Patrol Post fled into the jungle in crouched, zigzagging panic when an object he believed to be a metal house abruptly growled and moved. His name became 'Land Rover'.

Names were nicknames. They stuck for a while, then a new one came along. Only when the new (Australian) government began insisting that they use the same name for official dealings, especially in the annual census soon instituted, did formal names emerge.”

— E. Richard Sorenson, “Preconquest Consciousness”

I want dig a little bit deeper into this heresy as, unlike some of the others, this is one that I actually avow. First, I really mean it when I say that our modern naming conventions (roughly, a permanent personal given name and inherited surname bestowed at birth) only exist so that governments could more easily tax us. From Scott Alexander’s (excellent) review of James C. Scott’s Seeing Like a State.

Scott describes the spread of surnames. Peasants didn’t like permanent surnames. Their own system was quite reasonable for them: John the baker was John Baker, John the blacksmith was John Smith, John who lived under the hill was John Underhill, John who was really short was John Short. The same person might be John Smith and John Underhill in different contexts, where his status as a blacksmith or place of origin was more important.

But the government insisted on giving everyone a single permanent name, unique for the village, and tracking who was in the same family as whom. Resistance was intense:

What evidence we have suggests that second names of any kind became rare as distance from the state’s fiscal reach increased. Whereas one-third of the households in Florence declared a second name, the proportion dropped to one-fifth for secondary towns and to one-tenth in the countryside. It was not until the seventeenth century that family names crystallized in the most remote and poorest areas of Tuscany – the areas that would have had the least contact with officialdom. […]

State naming practices, like state mapping practices, were inevitably associated with taxes (labor, military service, grain, revenue) and hence aroused popular resistance. The great English peasant rising of 1381 (often called the Wat Tyler Rebellion) is attributed to an unprecedented decade of registration and assessments of poll taxes. For English as well as for Tuscan peasants, a census of all adult males could not but appear ominous, if not ruinous.

The same issues repeated themselves a few hundred years later when Europe started colonizing other continents. Again they encountered a population with naming systems they found unclear and unsuitable to taxation. But since colonial states had more control over their subjects than the relatively weak feudal monarchies of the Middle Ages, they were able to deal with it in one fell swoop, sometimes comically so:

Nowhere is this better illustrated than in the Philippines under the Spanish. Filipinos were instructed by the decree of November 21, 1849 to take on permanent Hispanic surnames. […]

Each local official was to be given a supply of surnames sufficient for his jurisdiction, “taking care that the distribution be made by letters of the alphabet.” In practice, each town was given a number of pages from the alphabetized [catalog], producing whole towns with surnames beginning with the same letter. In situations where there has been little in-migration in the past 150 years, the traces of this administrative exercise are still perfectly visible across the landscape. “For example, in the Bikol region, the entire alphabet is laid out like a garland over the provinces of Albay, Sorsogon, and Catanduanes which in 1849 belonged to the single jurisdiction of Albay. Beginning with A at the provincial capital, the letters B and C mark the towns along the cost beyond Tabaco to Wiki. We return and trace along the coast of Sorosgon the letters E to L, then starting down the Iraya Valley at Daraga with M, we stop with S to Polangui and Libon, and finish the alphabet with a quick tour around the island of Catanduas.

The confusion for which the decree is the antidote is largely that of the administrator and the tax collector. Universal last names, they believe, will facilitate the administration of justice, finance, and public order as well as make it simpler for prospective marriage partners to calculate their degree of consanguinity. For a utilitarian state builder of [Governor] Claveria’s temper, however, the ultimate goal was a complete and legible list of subjects and taxpayers.

When naming conventions are created by governments and for governments, they favor legibility and as a consequence, individuality and stability of identity. In my brief heretical statement, I suggested that our modern naming conventions have caused a species-wide shift towards a more narcissistic and egotistical mode of being. Maybe this goes too far (or not far enough…), but the more general idea I’m trying to raise is that personal nomenclature is never value neutral and never without cultural and psychological ramifications. In other words, we shouldn’t be surprised that our culture has become sterile, stagnant, and individualistic to a fault when those values are embedded in the way we name ourselves.

The global hegemony of governmentally-developed naming systems has crippled our imagination by removing alternative models of nomenclature. Consider the snapshot of indigenous New Guinean nomenclature provided in the above quote—names were fluid and not taken incredibly seriously, often being whimsically coined by friends or other members of the community because of some event or personal trait. This characterization of indigenous naming as “humorous exploratory play”, while certainly true to some extent, also reflects a deeply ingrained modern western bias—we can’t help but see temporary “nicknames” as unserious, not like our names, those momentous binding labels that can only be bestowed upon us by our parents. On the contrary, indigenous peoples often used names fluidly and treated them very seriously, in some ways much more seriously than we do now, seeing them as tools which can be used to help individuals grow and orient themselves within the tribe.

Consider the following account of Native American naming traditions:

“Native American children are given names that suit their personalities. If a name is given and proves to be a bad fit, the child’s name is changed. At adolescence, the given name may be changed again. As the adult progresses through life, new names can be awarded. Family and society award the new names, which provide the individual with a strong social bond to community as well as family. This naming tradition helps to motivate the individual to grow throughout life.

A Native American name can reflect your personality, what you accomplish, or what happens to you. The name Dancing Wind sounds beautiful to our ears, but Native Americans know that the dancing wind is an image for the tornado. This name warns of a volatile, angry disposition. It serves as a warning to others as well as an incentive to Dancing Wind to earn a new name. The name Bear is a common name like John. If the name is changed to Wounded Bear, society knows the individual is suffering and needs special care. If an individual accomplishes great things, a new name like “Eagle Eye” may be given to recognize the individual’s clear-sighted perception.

[…]

In addition to the psychological, social, and environmental dimensions of their names, Native Americans also have an added spiritual dimension with a secret, sacred name that is known only to the individual and the medicine man. If an individual has a secret sacred name that represents a pure essence, it can never be contaminated, no matter what happens to “the outside” name. This secret sacred name provides the individual with a pure spiritual core from which to regenerate should the individual experience any trauma.”

Naming systems are reflections of a culture’s values, but, as I’ve argued, it’s a two-way street—the way we name ourselves reinforces these values and frames how we think about ourselves and the world around us. When legibility, individuality, and stability of identity are the master values of our personal nomenclature, of course we will look for legible, de-personalized solutions (e.g. technology, laws, governmental programs) to society’s ills (environmental degradation, social isolation and loss of community, mental health and addiction, to name just a few). These solutions are only partial and always will be because they don’t get to the root of the problem: ourselves—who we are as people, what we value, and how we think. There is no shortcut to profound personal change, but a first step in the right direction might make all the difference—if we want to be the kind of people who value community and the natural world and who believe that people can grow and then perhaps we should name ourselves in a way that inspires us to be those kind of people.

Fascinating! Lots to think about.

Another thing I find interesting is what happens to your perception of your own name when you move to another country. For people of the new culture you get into, it signifies a different set of meanings, stereotypes attached to it; it even sounds differently when they say it. It’s almost like getting a new name that you have to get used to but you have no choice or any control over it.

It’s not something overdramatic or something you can’t cope with, just yet another insecurity from an expat 😅

Cheers!

Interesting one I found: Neil Armstrong’s name backwards is Gnorts Mr Alien!