PLAY is older than culture, for culture, however inadequately defined, always presupposes human society, and animals have not waited for man to teach them their playing. We can safely assert, even, that human civilization has added no essential feature to the general idea of play. Animals play just like men. We have only to watch young dogs to see that all the essentials of human play are present in their merry gambols. They invite one another to play by a certain ceremoniousness of attitude and gesture. They keep to the rule that you shall not bite, or not bite hard, your brother’s ear. They pretend to get terribly angry. And— what is most important—in all these doings they plainly experience tremendous fun and enjoyment. Such rompings of young dogs are only one of the simpler forms of animal play. There are other, much more highly developed forms: regular contests and beautiful performances before an admiring public.

Here we have at once a very important point: even in its simplest forms on the animal level, play is more than a mere physiological phenomenon or a psychological reflex. It goes beyond the confines of purely physical or purely biological activity. In play there is something “at play” which transcends the immediate needs of life and imparts meaning to the action. All play means something. If we call the active principle that makes up the essence of play, “instinct”, we explain nothing; if we call it “mind” or “will” we say too much. However we may regard it, the very fact that play has a meaning implies a non-materialistic quality in the nature of the thing itself. (Homo Ludens, Huizinga)

“Play is the exultation of the possible.”

— Martin Buber

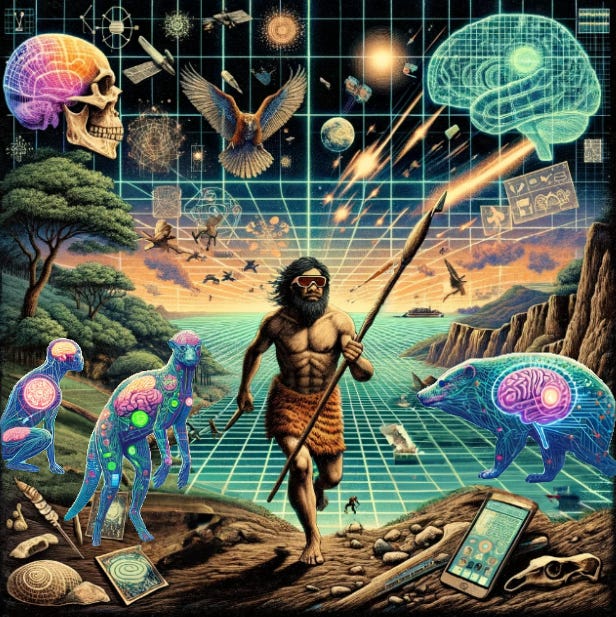

The Dawn of Everything (2021) by David Graeber and David Wengrow is a sweeping reimagining of human history that challenges the standard narrative of an inevitable, linear progression from primitive egalitarianism to the complex, hierarchical societies of today. The authors present a kaleidoscopic vision of pre-modern societies as fluid, experimental, and self-aware, capable of freely assembling and dismantling social structures at will. Across cultures and continents, from Ice Age hunter-gatherers to pre-Columbian cities, human beings are revealed as imaginative agents consciously playing with social and political possibilities, not the passive victims of material conditions that we are so often painted to be.

At the center of this historical vision is the idea of play as a serious generative force. Many of the institutions and technologies we take for granted—kingship, private property, agriculture, the wheel—emerged from rituals or festivals. The question for Graeber and Wengrow then is not how did hierarchy and inequality arise, but how did we get stuck in what were at first only transient forms of socio-economic organization? “If we started out just playing games, at what point did we forget that we were playing?”.

The Dawn of Everything is a work of history and anthropology; virtually nothing is said about the spiritual and cosmic dimensions of this historical vision, about the ‘what it all means’ of it all (if play is the medium, what is the message?). Dawn is not a prescriptive or forward-looking book either; little to nothing is said about how we may come to remember again that we are playing. These topics are a central focus of my ongoing work (my play), hence this introduction and the following compilation of relevant excerpts.

Laboratories of Social Possibility

The societies of the Great Plains created structures of coercive authority that lasted throughout the entire season of hunting and the rituals that followed, dissolving when they dispersed into smaller groups. But those of central Brazil dispersed into foraging bands as a way of asserting a political authority that was ineffectual in village settings. Among the Inuit, fathers ruled in the summertime; but in winter gatherings patriarchal authority and even norms of sexual propriety were challenged, subverted or simply melted away. The Kwakiutl were hierarchical at both times of year, but nonetheless maintained different forms of hierarchy, giving effective police powers to performers in the Midwinter Ceremonial (the ‘bear dancers’ and ‘fool dancers’) that could be exercised only during the actual performance of the ritual. At other times, aristocrats commanded great wealth but couldn’t give their followers direct orders. Many Central African forager societies are egalitarian all year round, but appear to alternate monthly between a ritual order dominated by men and another dominated by women.

In other words, there is no single pattern. The only consistent phenomenon is the very fact of alteration, and the consequent awareness of different social possibilities. What all this confirms is that searching for ‘the origins of social inequality’ really is asking the wrong question. If human beings, through most of our history, have moved back and forth fluidly between different social arrangements, assembling and dismantling hierarchies on a regular basis, maybe the real question should be ‘how did we get stuck?’ How did we end up in one single mode? How did we lose that political self-consciousness, once so typical of our species? How did we come to treat eminence and subservience not as temporary expedients, or even the pomp and circumstance of some kind of grand seasonal theatre but as inescapable elements of the human condition? If we started out just playing games, at what point did we forget that we were playing?

On play kings and playing with possible political forms:

We’ve already seen how, among societies like the Inuit or Kwakiutl, times of seasonal congregation were also ritual seasons, almost entirely given over to dances, rites and dramas. Sometimes these could involve creating temporary kings or even ritual police with real coercive powers (though often, peculiarly, these ritual police doubled as clowns). In other cases, they involved dissolving norms of hierarchy and propriety, as in the Inuit midwinter orgies. This dichotomy can still be observed in festive life almost everywhere. In the European Middle Ages, to take a familiar example, saints’ days alternated between solemn pageants where all the elaborate ranks and hierarchies of feudal life were made manifest (much as they still are in, say, a college graduation ceremony, when we temporarily revert to medieval garb), and crazy carnivals in which everyone played at ‘turning the world upside down’. In carnival, women might rule over men, children be put in charge of government, servants could demand work from their masters, ancestors could return from the dead, ‘carnival kings’ could be crowned and then dethroned, giant monuments like wicker dragons built and set on fire, or all formal ranks might even disintegrate into one or other form of Bacchanalian chaos.

Just as with seasonality, there’s no consistent pattern. Ritual occasions can either be much more stiff and formal, or much more wild and playful, than ordinary life. Alternatively, like funerals and wakes, they can slip back and forth between the two. The same seems to be true of festive life almost everywhere, whether it’s Peru, Benin or China. This is why anthropologists often have such trouble defining what a ‘ritual’ even is. If you start from the solemn ones, ritual is a matter of etiquette, propriety: High Church ritual, for example, is really just a very elaborate version of table manners. Some have gone so far as to argue that what we call ‘social structure’ only really exists during rituals: think here of families that only exist as a physical group during marriages and funerals, during which times questions of rank and priority have to be worked out by who sits at which table, who speaks first, who gets the topmost cut of the hump of a sacrificed water buffalo, or the first slice of wedding cake.

But sometimes festivals are moments where entirely different social structures take over, such as the ‘youth abbeys’ that seem to have existed across medieval Europe, with their Boy Bishops, May Queens, Lords of Misrule, Abbots of Unreason and Princes of Sots, who during the Christmas, Mayday or carnival season temporarily took over many of the functions of government and enacted a bawdy parody of government’s everyday forms. So there’s another school of thought which says that rituals are really exactly the opposite. The really powerful ritual moments are those of collective chaos, effervescence, liminality or creative play, out of which new social forms can come into the world.

There is also a centuries-long, and frankly not very enlightening, debate over whether the most apparently subversive popular festivals were really as subversive as they seem; or if they are really conservative, allowing common folk a chance to blow off a little steam and give vent to their baser instincts before returning to everyday habits of obedience. It strikes us that all this rather misses the point.

What’s really important about such festivals is that they kept the old spark of political self-consciousness alive. They allowed people to imagine that other arrangements are feasible, even for society as a whole, since it was always possible to fantasize about carnival bursting its seams and becoming the new reality. In the popular Babylonian story of Semiramis, the eponymous servant girl convinces the Assyrian king to let her be ‘Queen for a Day’ during some annual festival, promptly has him arrested, declares herself empress and leads her new armies to conquer the world. May Day came to be chosen as the date for the international workers’ holiday largely because so many British peasant revolts had historically begun on that riotous festival. Villagers who played at ‘turning the world upside’ would periodically decide they actually preferred the world upside down, and took measures to keep it that way.

Medieval peasants often found it much easier than medieval intellectuals to imagine a society of equals. Now, perhaps, we begin to understand why. Seasonal festivals may be a pale echo of older patterns of seasonal variation – but, for the last few thousand years of human history at least, they appear to have played much the same role in fostering political self-consciousness, and as laboratories of social possibility. The first kings may well have been play kings. Then they became real kings. Now most (but not all) existing kings have been reduced once again to play kings – as least insofar as they mainly perform ceremonial functions and no longer wield real power. But even if all monarchies, including ceremonial monarchies, were to disappear, some people would still play at being kings.

Even in the European Middle Ages, in places where monarchy was unquestioned as a mode of government, ‘Abbots of Unreason’, Yuletide Kings and the like tended to be chosen either by election or by sortition (lottery), the very forms of collective decision-making that resurfaced, apparently out of nowhere, in the Enlightenment. (What’s more, such figures tended to exercise power much in the manner of indigenous American chiefs: either limited to very circumscribed contexts, like the war chiefs who could give orders only during military expeditions; or like village chiefs who were arrayed with formal honours but couldn’t tell anybody what to do.) For a great many societies, the festive year could be read as a veritable encyclopaedia of possible political forms.

[…]

With such institutional flexibility comes the capacity to step outside the boundaries of any given structure and reflect; to both make and unmake the political worlds we live in. If nothing else, this explains the ‘princes’ and ‘princesses’ of the last Ice Age, who appear to show up, in such magnificent isolation, like characters in some kind of fairy tale or costume drama. Maybe they were almost literally so.

On play kings and real freedoms and vice versa:

American citizens have the right to travel wherever they like – provided, of course, they have the money for transport and accommodation. They are free from ever having to obey the arbitrary orders of superiors – unless, of course, they have to get a job. In this sense, it is almost possible to say the Wendat had play chiefs and real freedoms, while most of us today have to make do with real chiefs and play freedoms. Or to put the matter more technically: what the Hadza, Wendat or ‘egalitarian’ people such as the Nuer seem to have been concerned with were not so much formal freedoms as substantive ones. They were less interested in the right to travel than in the possibility of actually doing so (hence, the matter was typically framed as an obligation to provide hospitality to strangers). Mutual aid – what contemporary European observers often referred to as ‘communism’ – was seen as the necessary condition for individual autonomy.

On Homo Ludens in Minoan Art:

Cretan palaces were unfortified, and Minoan art makes almost no reference to war, dwelling instead on scenes of play and attention to creature comforts.

What these scenes celebrate, as he eloquently puts it, is quite the opposite of politics: it is the ‘ritually induced release from individuality, and an ecstasy of being that is overtly erotic and spiritual at the same time (ek-stasis, “standing beyond oneself”) – a cosmos that both nurtures and ignores the individual, that vibrates with inseparable sexual energies and spiritual epiphanies’. There are no heroes in Minoan art – only players. The Crete of the palaces was the realm of Homo ludens.

On self-creation and the possibility of reinvention:

If, as many are suggesting, our species’ future now hinges on our capacity to create something different (say, a system in which wealth cannot be freely transformed into power, or where some people are not told their needs are unimportant, or that their lives have no intrinsic worth), then what ultimately matters is whether we can rediscover the freedoms that make us human in the first place. As long ago as 1936, the prehistorian V. Gordon Childe wrote a book called Man Makes Himself. Apart from the sexist language, this is the spirit we wish to invoke. We are projects of collective self-creation. What if we approached human history that way? What if we treat people, from the beginning, as imaginative, intelligent, playful creatures who deserve to be understood as such? What if, instead of telling a story about how our species fell from some idyllic state of equality, we ask how we came to be trapped in such tight conceptual shackles that we can no longer even imagine the possibility of reinventing ourselves?

The Historical Imagination (or lack thereof)

Ever since Adam Smith, those trying to prove that contemporary forms of competitive market exchange are rooted in human nature have pointed to the existence of what they call ‘primitive trade’. Already tens of thousands of years ago, one can find evidence of objects – very often precious stones, shells or other items of adornment – being moved around over enormous distances. Often these were just the sort of objects that anthropologists would later find being used as ‘primitive currencies’ all over the world. Surely this must prove capitalism in some form or another has always existed?

The logic is perfectly circular. If precious objects were moving long distances, this is evidence of ‘trade’ and, if trade occurred, it must have taken some sort of commercial form; therefore, the fact that, say, 3,000 years ago Baltic amber found its way to the Mediterranean, or shells from the Gulf of Mexico were transported to Ohio, is proof that we are in the presence of some embryonic form of market economy. Markets are universal. Therefore, there must have been a market. Therefore, markets are universal. And so on.

All such authors are really saying is that they themselves cannot personally imagine any other way that precious objects might move about. But lack of imagination is not itself an argument. It’s almost as if these writers are afraid to suggest anything that seems original, or, if they do, feel obliged to use vaguely scientific-sounding language (‘trans-regional interaction spheres’, ‘multi-scalar networks of exchange’) to avoid having to speculate about what precisely those things might be. In fact, anthropology provides endless illustrations of how valuable objects might travel long distances in the absence of anything that remotely resembles a market economy.

The founding text of twentieth-century ethnography, Bronisław Malinowski’s 1922 Argonauts of the Western Pacific, describes how in the ‘kula chain’ of the Massim Islands off Papua New Guinea, men would undertake daring expeditions across dangerous seas in outrigger canoes, just in order to exchange precious heirloom arm-shells and necklaces for each other (each of the most important ones has its own name, and history of former owners) – only to hold it briefly, then pass it on again to a different expedition from another island. Heirloom treasures circle the island chain eternally, crossing hundreds of miles of ocean, arm-shells and necklaces in opposite directions. To an outsider, it seems senseless. To the men of the Massim it was the ultimate adventure, and nothing could be more important than to spread one’s name, in this fashion, to places one had never seen.

Is this ‘trade’? Perhaps, but it would bend to breaking point our ordinary understandings of what that word means. There is, in fact, a substantial ethnographic literature on how such long-distance exchange operates in societies without markets. Barter does occur: different groups may take on specialities – one is famous for its feather-work, another provides salt, in a third all women are potters – to acquire things they cannot produce themselves; sometimes one group will specialize in the very business of moving people and things around. But we often find such regional networks developing largely for the sake of creating friendly mutual relations, or having an excuse to visit one another from time to time; and there are plenty of other possibilities that in no way resemble ‘trade’.

Let’s list just a few, all drawn from North American material, to give the reader a taste of what might really be going on when people speak of ‘long distance interaction spheres’ in the human past:

Dreams or vision quests: among Iroquoian-speaking peoples in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries it was considered extremely important literally to realize one’s dreams. Many European observers marvelled at how Indians would be willing to travel for days to bring back some object, trophy, crystal or even an animal like a dog that they had dreamed of acquiring. Anyone who dreamed about a neighbour or relative’s possession (a kettle, ornament, mask and so on) could normally demand it; as a result, such objects would often gradually travel some way from town to town. On the Great Plains, decisions to travel long distances in search of rare or exotic items could form part of vision quests.

Travelling healers and entertainers: in 1528, when a shipwrecked Spaniard named Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca made his way from Florida across what is now Texas to Mexico, he found he could pass easily between villages (even villages at war with one another) by offering his services as a magician and curer. Curers in much of North America were also entertainers, and would often develop significant entourages; those who felt their lives had been saved by the performance would, typically, offer up all their material possessions to be divided among the troupe. By such means, precious objects could easily travel very long distances.

Women’s gambling: women in many indigenous North American societies were inveterate gamblers; the women of adjacent villages would often meet to play dice or a game played with a bowl and plum stone, and would typically bet their shell beads or other objects of personal adornment as the stakes. One archaeologist versed in the ethnographic literature, Warren DeBoer, estimates that many of the shells and other exotica discovered in sites halfway across the continent had got there by being endlessly wagered, and lost, in intervillage games of this sort, over very long periods of time.

We could multiply examples, but assume that by now the reader gets the broader point we are making. When we simply guess as to what humans in other times and places might be up to, we almost invariably make guesses that are far less interesting, far less quirky – in a word, far less human than what was likely going on.

The Origin(s) of Agriculture and Ritual Play

‘Tell me this,’ writes Plato:

“Would a serious and intelligent farmer, with seeds he cared about and wished to grow to fruition, sow them in summer in the gardens of Adonis and rejoice as he watched them become beautiful in a matter of eight days; or if he did it at all, would he do this for fun and festivity? For things he really was serious about, would he not use his farmer’s craft, plant them in a suitable environment, and be content if everything he planted came to maturity in the eighth month?”

The gardens of Adonis, to which Plato is referring here, were a sort of festive speed farming which produced no food. For the philosopher, they offered a convenient simile for all things precocious, alluring, but ultimately sterile. In the dog days of summer, when nothing can grow, the women of ancient Athens fashioned these little gardens in baskets and pots. Each held a mix of quick-sprouting grain and herbs. The makeshift seedbeds were carried up ladders on to the flat roofs of private houses and left to wilt in the sun: a botanical re-enactment of the premature death of Adonis, the fallen hunter, slain in his prime by a wild boar. Then, beyond the public gaze of men and civic authority, began the rooftop rites. Open to women from all classes of Athenian society, including prostitutes, these were rites of grieving but also wanton drunkenness, and no doubt other forms of ecstatic behaviour as well.

Historians agree that the roots of this women’s cult lie in Mesopotamian fertility rites of Dumuzi/Tammuz, the shepherd-god and personification of plant life, mourned on his death each summer. Most likely the worship of Adonis, his ancient Greek incarnation, spread westwards to Greece from Phoenicia in the wake of Assyrian expansion, in the seventh century BC. Nowadays, some scholars see the whole thing as a riotous subversion of patriarchal values: an antithesis to the staid and proper state-sponsored Thesmophoria (the autumn festival of the Greek fertility goddess, Demeter), celebrated by the wives of Athenian citizens and dedicated to the serious farming on which the life of the city depended. Others read the story of Adonis the other way round, as a requiem for the primeval drama of serious hunting, cast into shadow by the advent of agriculture, but not forgotten – an echo of lost masculinity

Was farming from the very beginning about the serious business of producing more food to supply growing populations? Most scholars assume, as a matter of course, that this had to be the principal reason for its invention. But maybe farming began as a more playful or even subversive kind of process – or perhaps even as a side effect of other concerns, such as the desire to spend longer in particular kinds of locations, where hunting and trading were the real priorities. Which of these two ideas really embodies the spirit of the first agriculturalists; is it the stately and pragmatic Thesmophoria, or the playful and self-indulgent gardens of Adonis?

[…]

Could it be that, in the same way that play farming – our term for those loose and flexible methods of cultivation which leave people free to pursue any number of other seasonal activities – turned into more serious agriculture, play kingdoms began to take on more substance as well?

On ritual play, social experimentation, and where it all went wrong:

‘Gardens of Adonis’ are a fitting symbol here. Knowledge about the nutritious properties and growth cycles of what would later become staple crops, feeding vast populations – wheat, rice, corn – was initially maintained through ritual play farming of exactly this sort. Nor was this pattern of discovery limited to crops. Ceramics were first invented, long before the Neolithic, to make figurines, miniature models of animals and other subjects, and only later cooking and storage vessels. Mining is first attested as a way of obtaining minerals to be used as pigments, with the extraction of metals for industrial use coming only much later. Mesoamerican societies never employed wheeled transport; but we know they were familiar with spokes, wheels and axles since they made toy versions of them for children. Greek scientists famously came up with the principle of the steam engine, but only employed it to make temple doors that appeared to open of their own accord, or similar theatrical illusions. Chinese scientists, equally famously, first employed gunpowder for fireworks. For most of history, then, the zone of ritual play constituted both a scientific laboratory and, for any given society, a repertory of knowledge and techniques which might or might not be applied to pragmatic problems. Recall, for example, the ‘Little Old Men’ of the Osage and how they combined research and speculation on the principles of nature with the management and periodic reform of their constitutional order; how they saw these as ultimately the same project and kept careful (oral) records of their deliberations. Did the Neolithic town of Çatalhöyük or the Tripolye mega-sites host similar colleges of ‘Little Old Women’? We cannot know for certain, but it strikes us as quite likely, given the shared rhythms of social and technical innovation that we observe in each case and the attention to female themes in their art and ritual. If we are trying to frame more interesting questions to ask of history, this might be one: is there a positive correlation between what is usually called ‘gender equality’ (which might better be termed, simply, ‘women’s freedom’) and the degree of innovation in a given society?

Choosing to describe history the other way round, as a series of abrupt technological revolutions, each followed by long periods when we were prisoners of our own creations, has consequences. Ultimately it is a way of representing our species as decidedly less thoughtful, less creative, less free than we actually turn out to have been. It means not describing history as a continual series of new ideas and innovations, technical or otherwise, during which different communities made collective decisions about which technologies they saw fit to apply to everyday purposes, and which to keep confined to the domain of experimentation or ritual play. What is true of technological creativity is, of course, even more true of social creativity. One of the most striking patterns we discovered while researching this book – indeed, one of the patterns that felt most like a genuine breakthrough to us – was how, time and again in human history, that zone of ritual play has also acted as a site of social experimentation – even, in some ways, as an encyclopaedia of social possibilities.

We are not the first to suggest this. In the mid twentieth century, a British anthropologist named A. M. Hocart proposed that monarchy and institutions of government were originally derived from rituals designed to channel powers of life from the cosmos into human society. He even suggested at one point that ‘the first kings must have been dead kings’, and that individuals so honoured only really became sacred rulers at their funerals. Hocart was considered an oddball by his fellow anthropologists and never managed to secure a permanent job at a major university. Many accused him of being unscientific, just engaging in idle speculation. Ironically, as we’ve seen, it is the results of contemporary archaeological science that now oblige us to start taking his speculations seriously. To the astonishment of many, but much as Hocart predicted, the Upper Palaeolithic really has produced evidence of grand burials, carefully staged for individuals who indeed seem to have attracted spectacular riches and honours, largely in death.

The principle doesn’t just apply to monarchy or aristocracy, but to other institutions as well. We have made the case that private property first appears as a concept in sacred contexts, as do police functions and powers of command, along with (in later times) a whole panoply of formal democratic procedures, like election and sortition, which were eventually deployed to limit such powers.

Here is where things get complicated. To say that, for most of human history, the ritual year served as a kind of compendium of social possibilities (as it did in the European Middle Ages, for instance, when hierarchical pageants alternated with rambunctious carnivals), doesn’t really do the matter justice. This is because festivals are already seen as extraordinary, somewhat unreal, or at the very least as departures from the everyday order. Whereas, in fact, the evidence we have from Palaeolithic times onwards suggests that many – perhaps even most – people did not merely imagine or enact different social orders at different times of year, but actually lived in them for extended periods of time. The contrast with our present situation could not be more stark. Nowadays, most of us find it increasingly difficult even to picture what an alternative economic or social order would be like. Our distant ancestors seem, by contrast, to have moved regularly back and forth between them.

If something did go terribly wrong in human history – and given the current state of the world, it’s hard to deny something did – then perhaps it began to go wrong precisely when people started losing that freedom to imagine and enact other forms of social existence, to such a degree that some now feel this particular type of freedom hardly even existed, or was barely exercised, for the greater part of human history. Even those few anthropologists, such as Pierre Clastres and later Christopher Boehm, who argue that humans were always able to imagine alternative social possibilities, conclude – rather oddly – that for roughly 95 percent of our species’ history those same humans recoiled in horror from all possible social worlds but one: the small-scale society of equals. Our only dreams were nightmares: terrible visions of hierarchy, domination and the state. In fact, as we’ve seen, this is clearly not the case.

On the Little Old Men of the Osage and socio-political self-consciousness:

Records, La Flesche observed, had also been kept of particular discussions in which various results of this study of nature were debated and discussed. Osage concluded that this force was ultimately unknowable and gave it the name Wakonda, which could alternately be translated as ‘God’ or ‘Mystery’. Through lengthy investigation, La Flesche notes, elders determined that life and motion was produced by the interaction of two principles – sky and earth – and therefore they divided their own society in the same way, arranging it so that men from one division could only take wives from the other. A village was a model of the universe, and as such a form of ‘supplication’ to its animating power.

Initiation through the levels of understanding required a substantial investment of time and wealth, and most Osage only attained the first or second tier. Those who reached the top were known collectively as the Nohozhinga or ‘Little Old Men’ (though some were women), and were also the ultimate political authorities. While every Osage was expected to spend an hour after sunrise in prayerful reflection, the Little-Old-Men carried out daily deliberations on questions of natural philosophy and their specific relevance to political issues of the day. They also kept a history of the most important discussions. La Flesche explains that, periodically, particularly perplexing questions would come up: either about the nature of the visible universe, or about the application of these understandings to human affairs. At this point it was customary for two elders to retreat to a secluded spot in the wilderness and carry out a vigil for four to seven days, to ‘search their minds’, before returning with a report on their conclusions.

The Nohozhinga were the body that met daily to discuss affairs of state.66 While larger assemblies could be called to ratify decisions, they were the effective government. In this sense one could say that the Osage were a theocracy, though it would be more accurate, perhaps, to say there was no difference between officials, priests and philosophers. All were title-bearing officials, including the ‘soldiers’ assigned to help chiefs enforce their decisions, while ‘Protectors of the Land’ assigned to hunt down and kill outsiders who poached game were also religious figures. As for the history: it begins in mythic terms, as an ‘allegorical fable’, then rapidly turns into a story about institutional reform.

In the beginning, the three main divisions – Sky People, Earth People and Water People – descended into the world and set out in search of its indigenous inhabitants. When they located these inhabitants, they were discovered to be in a repulsive state: living amid filth, bones and carrion, feeding on offal, rotting flesh, even each other. Despite this more-than Hobbesian situation, the Isolated Earth People (as they came to be known) were also powerful sorcerers, capable of using the four winds to destroy life everywhere. Only the chief of the Water division had the courage to enter their village, negotiate with their leader and convince his people to abandon their murderous and unsanitary ways. In the end, he persuaded the Isolated Earth People to join them in a federation – to ‘move to a new country’, free from the pollution of decaying corpses. This is how the circular village plan was first conceived, with the one-time wizards placed opposite Water, at the eastern door, where they were in charge of the House of Mystery, used for all peaceful rituals, and where all children were brought to be named. The Bear clan of the Earth division was put in charge of an opposite House of Mystery, responsible for rituals concerning war. The problem was that the Isolated Earth People, while no longer murderous, did not prove particularly effective allies either. Before long everything had descended into continual strife and feuding, until the Water division demanded another ‘move to a new country’, which initiated, among other things, an elaborate process of constitutional reform, making declarations of war impossible without the acquiescence of every clan. This too proved problematic over time, since it meant that if an external enemy entered the country, at least a week was required to organize a military response. Eventually it became necessary yet again to ‘move to another country’, which this time involved the creation of a new, decentralized clan-by-clan system of military authority. This in turn led to a new crisis and round of reforms: in this case, the separation of civil and military affairs with the creation of a hereditary peace chief for each division, their houses placed on the east and west extremes of the village, and various subordinate officials, as well as a parallel structure with responsibility for all five major Osage villages.

We will not linger over the details. But two elements of the story deserve emphasis. The first is that the narrative sets off from the neutralization of arbitrary power: the taming of the Isolated Earth People’s leader – the chief sorcerer, who abuses his deadly knowledge – by according him some central position in a new system of alliances. This is a common story among the descendants of groups that had formerly come under the influence of Mississippian civilization. In the process of co-opting their leader, the destructive ritual knowledge once held by the Isolated Earth People was, eventually, distributed to everyone, along with elaborate checks and balances concerning its use. The second is that even the Osage, who ascribed key roles to sacred knowledge in their political affairs, in no sense saw their social structure as something given from on high but rather as a series of legal and intellectual discoveries – even breakthroughs.

On ecological flexibility and freedom:

Historically speaking, there is no direct connection among these cases; but what they show, collectively, is how the fate of early farming societies often hinged less on ‘ecological imperialism’ than on what we might call – to adapt a phrase from the pioneer of social ecology, Murray Bookchin – an ‘ecology of freedom’. By this we mean something quite specific. If peasants are people ‘existentially involved in cultivation’, then the ecology of freedom (‘play farming’, in short) is precisely the opposite condition. The ecology of freedom describes the proclivity of human societies to move (freely) in and out of farming; to farm without fully becoming farmers; raise crops and animals without surrendering too much of one’s existence to the logistical rigours of agriculture; and retain a food web sufficiently broad as to prevent cultivation from becoming a matter of life and death. It is just this sort of ecological flexibility that tends to be excluded from conventional narratives of world history, which present the planting of a single seed as a point of no return.

On time-allocation studies and the self-conscious rejection of agriculture:

Moreover, the results of those early time-allocation studies came as an enormous surprise. It’s worth bearing in mind that, in the post-war decades, most anthropologists and archaeologists still very much took for granted the old nineteenth-century narrative of humanity’s primordial ‘struggle for existence’. To our ears, much of the rhetoric commonplace at the time, even among the most sophisticated scholars, sounds startlingly condescending: ‘A man who spends his whole life following animals just to kill them to eat,’ wrote the prehistorian Robert Braidwood in 1957, ‘or moving from one berry patch to another, is really living just like an animal himself.’ Yet these first quantitative studies comprehensively disproved such pronouncements. They showed that, even in quite inhospitable environments like the deserts of Namibia or Botswana, foragers could easily feed everyone in their group and still have three to five days per week left for engaging in such extremely human activities as gossiping, arguing, playing games, dancing or travelling for pleasure. Researchers in the 1960s were also beginning to realize that, far from agriculture being some sort of remarkable scientific advance, foragers (who after all tended to be intimately familiar with all aspects of the growing cycles of food plants) were perfectly aware of how one might go about planting and harvesting grains and vegetables. They just didn’t see any reason why they should. ‘Why should we plant,’ one !Kung informant put it – in a phrase cited ever since in a thousand treatises on the origins of farming – ‘when there are so many mongongo nuts in the world?’ Indeed, concluded Sahlins, what some prehistorians had assumed to be technical ignorance was really a self-conscious social decision: such foragers had ‘rejected the Neolithic Revolution in order to keep their leisure’. Anthropologists were still struggling to come to terms with all this when Sahlins stepped in to draw the larger conclusions. The ancient forager ethos of leisure (the ‘Zen road to affluence’) only broke down, or so Sahlins surmised, when people finally – for whatever reasons – began to settle in one place and accept the toils of agriculture. They did so at a terrible cost. It wasn’t just ever-increasing hours of toil that followed but, for most, poverty, disease, war and slavery – all fuelled by endless competition and the mindless pursuit of new pleasures, new powers and new forms of wealth. With one deft move, Sahlins’s ‘Original Affluent Society’ used the results of time-allocation studies to pull the rug from under the traditional story of human civilization. Like Woodburn, Sahlins brushes aside Rousseau’s version of the Fall – the idea that, too foolish to reflect on the likely consequences of our actions in assembling, stockpiling and guarding property, we ‘ran blindly for our chains’ – and takes us straight back to the Garden of Eden. If rejecting farming was a conscious choice, then so was that act of embracing it. We chose to eat of the fruit of the tree of knowledge, and for this we were punished. As St Augustine put it, we rebelled against God, and God’s judgment was to cause our own desires to rebel against our rational good sense; our punishment for original sin is the infinity of our new desires.

Mesoamerican Ball Games

Any further assessment of Olmec political structure has to reckon with what many consider its signature achievement: a series of absolutely colossal sculpted heads. These remarkable objects are free-standing, carved from tons of basalt, and of a quality comparable with the finest ancient Egyptian stonework. Each must have taken untold hours of grinding to produce. These sculptures appear to be representations of Olmec leaders, but, intriguingly, they are depicted wearing the leather helmets of ball players. All the known examples are sufficiently similar that each seems to reflect some kind of standard ideal of male beauty; but, at the same time, each is also different enough to be seen as a unique portrait of a particular, individual champion.

No doubt there were also actual ball-courts – though these have proved surprisingly elusive in the archaeological record – and while we obviously don’t know what kind of game was played, if they were anything like later Maya and Aztec ball games it likely took place in a long and narrow court, with two teams from high-ranking families competing for fame and honour by striking a heavy rubber ball with the hips and buttocks. It seems both reasonable and logical to conclude that there was a fairly direct relationship between competitive games and the rise of an Olmec aristocracy. Without written evidence it’s hard to say much more, but looking a bit closer at later Mesoamerican ball games might at least give us a sense of how this worked in practice.

Stone ball-courts were common features of Classic Maya cities, alongside royal residences and pyramid-temples. Some were purely ceremonial; others were actually used for sport. The chief Maya gods were themselves ball players. In the K’iche Maya epic Popol Vuh a ball game provides the setting in which mortal heroes and underworld gods collide, leading to the birth of the Hero Twins Hunahpu and Xbalanque, who go on to beat the gods at their own deadly game and ascend to take their own place among the stars.

The fact that the greatest known Maya epic centres on a ball game gives us a sense of how central the sport was to Maya notions of charisma and authority. So too, in a more visceral way, does an inscribed staircase built at Yaxchilán to mark the accession (in AD 752) of what was probably its most famous king, known as Bird Jaguar the Great. On the central block he appears as a ball player. Flanked by two dwarf attendants, the king prepares to strike a huge rubber ball containing the body of a human captive – bound, broken and bundled – as it tumbles down a flight of stairs. Capturing high-ranking enemies to be held for ransom or, failing payment, to be killed at ball games was a major objective of Maya warfare. This particular unfortunate figure may be a certain Jewelled Skull, a noble from a rival city, whose humiliation was so important to Bird Jaguar that he also made it the central feature of a carved lintel on a nearby temple.

In some parts of the Americas, competitive sports served as a substitute for war. Among the Classic Maya, one was really an extension of the other. Battles and games formed part of an annual cycle of royal competitions, played for life and death. Both are recorded on Maya monuments as key events in the lives of rulers. Most likely, these elite games were also mass spectacles, cultivating a particular sort of urban public – the sort that relishes gladiatorial contests, and thereby comes to understand politics in terms of opposition. Centuries later, Spanish conquistadors described Aztec versions of the ball game played at Tenochtitlan, where players confronted each other amid racks of human skulls. They reported how reckless commoners, carried away in the competitive fervour of the tournament, would sometimes lose all they had or even gamble themselves into slavery. The stakes were so high that, should a player actually send a ball through one of the stone hoops adorning the side of the court (these were made so small as to render it nearly impossible; normally the game was won in other ways), the contest ended immediately, and the player who performed the miracle received all the goods wagered, as well as any others he might care to pillage from the onlookers.

Digital spaces seem to be the only path to recreate these dynamics (though the modern drug soaked electronic music festival seems to be filling one of the old niches). Large group political experiments on Minecraft are a recent example that stands out.