STRANGE AND MACABRE MISCELLANEA

1. Word of the month:

A whole view of life is captured in the Old English word dustsceawung ‘dust-watching’, or ‘contemplation of dust’. In Anglo-Saxon times, people would watch motes of dust float in the sunlight, and think about how the dust used to be other things. A book, a tree, the walls of a city—all will fade like the shouts of children on a summer day, or vanish like the memory of a dream.

Relevant:

2. Norm Macdonald

I remember a psychiatrist once telling me that I gamble in order to escape the reality of life, and I told him that’s why everyone does everything.

3. Marcus Aurelius:

How good it is when you have roast meat or suchlike foods before you, to impress on your mind that this is the dead body of a fish, this is the dead body of a bird or pig; and again, that the Falernian wine is the mere juice of grapes, and your purple edged robe simply the hair of a sheep soaked in shell-fish blood!

And in sexual intercourse that it is no more than the friction of a membrane and a spurt of mucus ejected.

How good these perceptions are at getting to the heart of the real thing and penetrating through it, so you can see it for what it is!

This should be your practice throughout all your life: when things have such a plausible appearance, show them naked, see their shoddiness, strip away their own boastful account of themselves.

Vanity is the greatest seducer of reason: when you are most convinced that your work is important, that is when you are most under its spell.

4. A short film:

5. From “The Minnesota Declaration” (Werner Herzog):

Facts cannot be underestimated as they have normative power. But they do not give us insight into the truth, or the illumination of poetry. Yes, the phone directory of Manhattan contains four million entries, all of them factually verifiable. But do we know why Jonathan Smith, correctly listed, cries into his pillow every night?

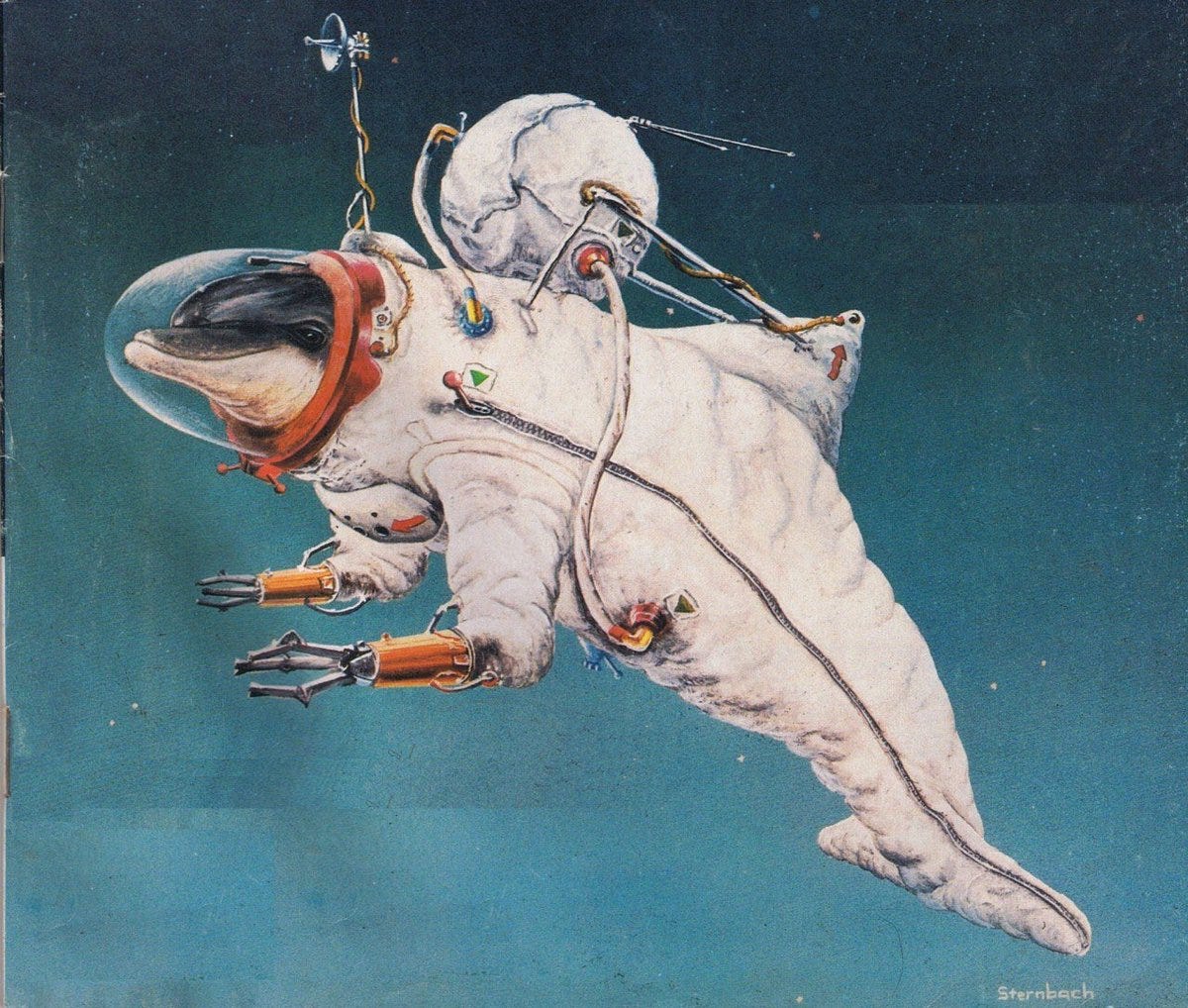

6. “How First Contact with Whale Civilization Could Unfold”

Before we put these questions to a sperm whale unit, we’d have to think hard about whether we’d act on the answers. Kristin Andrews told me a heartbreaking story about a chimpanzee named Bruno who was taught sign language at the University of Oklahoma. Bruno was encouraged to build his whole life around the practice of asking humans for things. But after a few years, the scientists’ grant ran out and he was transferred to a different facility. When one of the lab’s scientists visited him there, he was distressed to see that Bruno seemed upset. He kept signing Key and Out. The scientist had taught the chimpanzee to communicate, but even in the face of a clear request, the scientist couldn’t help him. “If these whales start saying Go away; make the ships leave, what will we do?” Andrews said. And how will it reflect on us as a society if we ignore them?

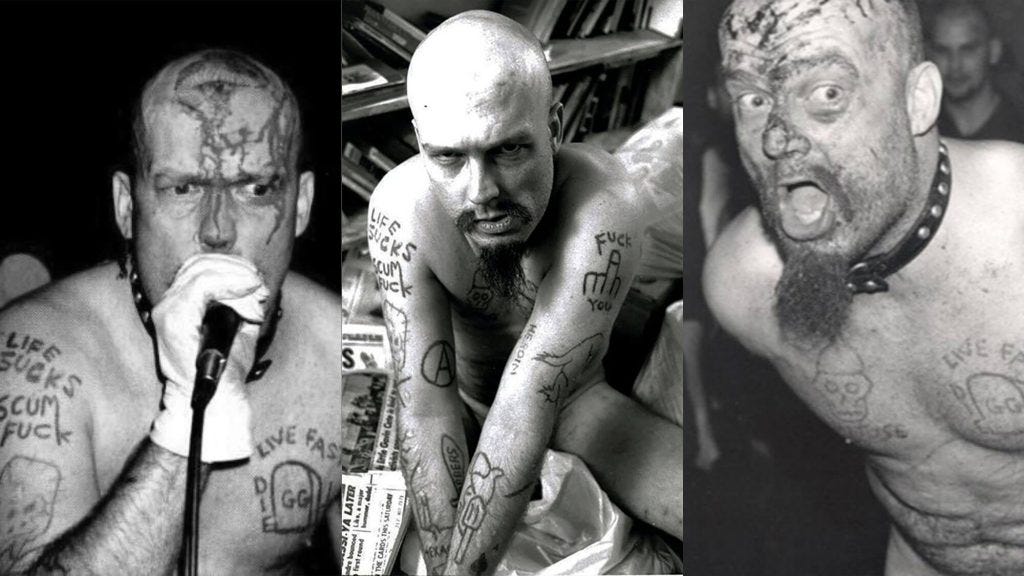

7. GG Allin

Kevin Michael “GG” Allin (born Jesus Christ Allin; 1956 – 1993) was an American punk rock musician who performed and recorded with many groups during his career. His live performances often featured transgressive acts, including self-mutilation, defecating on stage, and assaulting audience members, for which he was arrested and imprisoned on multiple occasions. AllMusic called him “the most spectacular degenerate in rock n’ roll history”.

Allin believed in some form of afterlife. He planned to kill himself onstage on Halloween many times in the late 1980s and early 1990s, but was stopped due to prison sentences around Halloween each year. He explained his views on death in the film Hated: GG Allin and the Murder Junkies, stating: “It’s like I’ve got this wild soul that just wants to get out of this life. It’s too confined in this life. I think that to take yourself out at your peak...if you could die at your peak, your strongest point, then your soul will be that much stronger in the next existence.”

8. A remarkable story from WWII:

The two men were Tibetan peasants. In the early 1930s, they embarked on a religious pilgrimage from the area around Yusho in Eastern Tibet to Lhasa. They were intent on entering a monastery-not an uncommon practice for young men in that culture. But early in their journey, as a result of an intense snowstorm, they became lost and wandered along the Dza (Mekong) river into Southeastern China, where they were captured by bandits. Shortly after their capture, the bandits packed up and marched into Northern China to join the Communists, taking the two young Tibetans with them.

From there, the two men escaped, and, after several years in which they probably skirted the northern lip of the Tibetan plateau, blundered into Central Russia, where they fell into the hands of the Russian authorities at Tashkent. The Germans had just invaded Russia, and the Tibetans were inducted into the Russian army and packed off to the Eastern Front as cannon fodder. Before long they were captured by the Germans—it wasn't clear whether by military misadventure or because they simply wandered away from their encampment and in behind the German lines.

Luckily, the German commandant involved in their capture didn't execute them. Instead, he had them transported to Poland, where they worked for a time in a concentration camp— Captain Surry couldn’t determine which one it was, or its size, only that people were, in the words of the Tibetans, coming there “to the smoky light”. But as winter approached, and under threat of the now-oncoming Russian armies, the concentration camp was dismantled and the two Tibetans were inducted into the German Army and transported to Normandy. There, as we know, once again they fell into the hands of a new authority.

Captain Surry went over the events again and again with the Tibetans, convinced that the riddle of their unlikely survival and their profound, elastic passivity in the face of hardship after hardship was eluding him. The modern world had done its worst to them, and yet had done nothing at all. The Tibetans were neither stupid men nor, on their own terms, were they ignorant.

Finally, it came to him. For ten years, these two men had believed that they were dead. Reluctantly, the Tibetans confirmed his theory and elaborated.

In their terms, their ordeal had been a test of their being, and a means, they hoped, of gaining Nirvana, however confusing and unorthodox those means were. They had survived because from the very first days they had believed that they were dead men caught in an unpredictable Bardo, or netherworld.

To the Tibetans, bodily survival had not been a goal, since they believed that they were already dead. They were traversing the netherworld in order to be reborn. They’d sought shelter, eaten and slept only because their bodies continued to make demands for shelter, food and sleep. These demands puzzled them, as did the duration of their ordeal and its peculiar difficulties.

9. “Why Childhood is Bad for Children” (Hannan, 2018)

This article asks whether being a child is, all things considered, good or bad for children. I defend a predicament view of childhood, which regards childhood as bad overall for children. I argue that four features of childhood make it regrettable: impaired capacity for practical reasoning, lack of an established practical identity, a need to be dominated, and profound and asymmetric vulnerability. I consider recent claims in the literature that childhood is good for children since it allows them to enjoy special goods that aren't available in adulthood, or which are harder to access in adulthood. I raise some difficulties for these claims. Then I argue that whatever version of these views survives my criticism will not establish that childhood is overall good for children. This is because the goods of childhood aren’t significant enough to outweigh the bad features associated with being a child. I conclude by suggesting that the badness of childhood for children means that we are likely to owe more to children than to adults.

10. He definitely clocked it

ART

12. Ganbrood

BORGES

13. “Death and the Compass” (1942)

He spoke; in his voice Lönnrot detected a fatigued triumph, a hatred the size of the universe, a sadness no smaller than that hatred; I was racked with fever, and the odious double-faced Janus who gazes toward the twilights of dusk and dawn terrorized my dreams and my waking. I learned to abominate my body, I came to feel that two eyes, two hands, two lungs are as monstrous as two faces. An Irishman attempted to convert me to the faith of Jesus; he repeated to me that famous axiom of the goyim: All roads lead to Rome. At night, my delirium nurtured itself on this metaphor: I sensed that the world was a labyrinth, from which it was impossible to flee, for all paths, whether they seemed to lead north or south, actually led to Rome, which was also the quadrilateral jail where my brother was dying and the country house of Triste-le-Roy. During those nights I swore by the god who sees from two faces, and by all the gods of fever and of mirrors, to weave a labyrinth around the man who had imprisoned my brother.

CONSCIOUSNESS

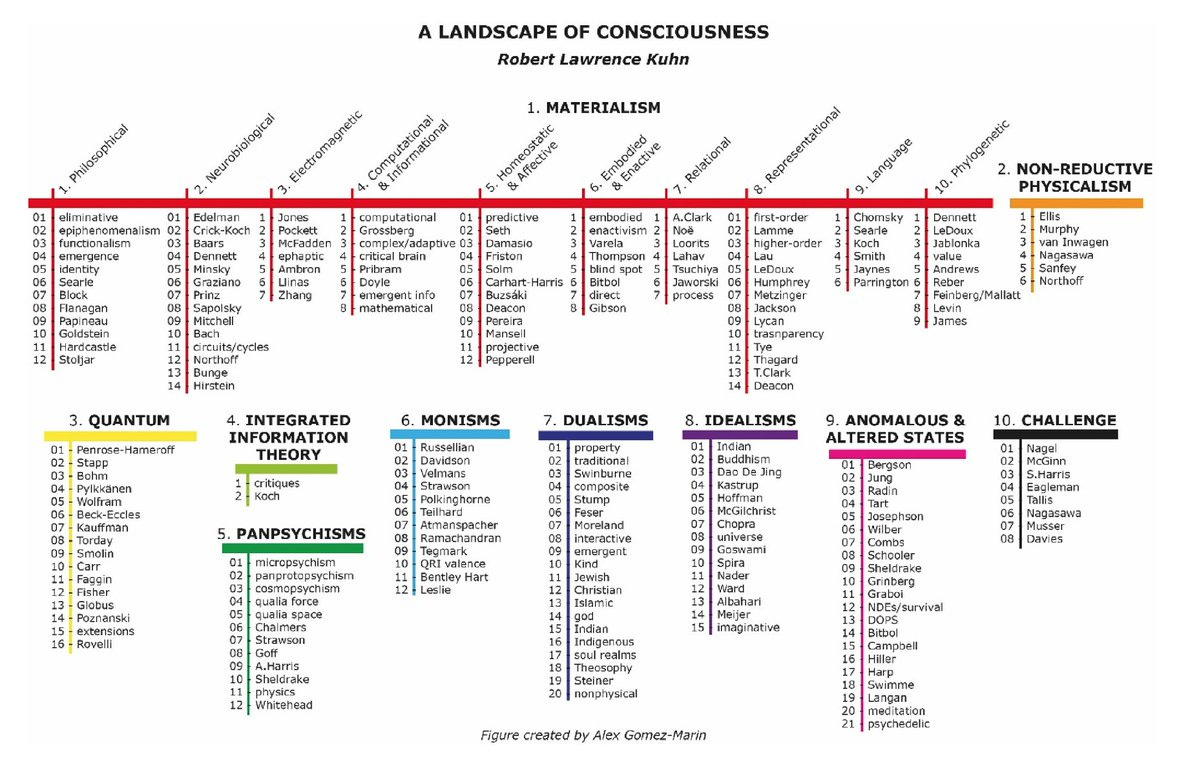

14. “A landscape of consciousness: Toward a taxonomy of explanations and implications” (Kuhn, 2024)

15. Recently published in Seeds of Science: “A Paradigm for AI Consciousness” (Johnson, 2024)

How can we create a container for knowledge about AI consciousness? This work introduces a new framework based on physicalism, decoherence, and symmetry. Major arguments include (1) atoms are a more sturdy ontology for grounding consciousness than bits, (2) Wolfram’s ‘branchial space’ is where an object’s true shape lives, (3) electromagnetism is a good proxy for branchial shape, (4) brains and computers have significantly different shapes in branchial space, (5) symmetry considerations will strongly inform a future science of consciousness, and (6) computational efficiency considerations may broadly hedge against “s-risk”.

SEEDS OF SCIENCE

16. One more time, an announcement from Seeds of Science:

Science needs a “third space” for science beyond academia and industry.

Seeds of Science is launching a new initiative, the SoS Research Collective, a first-of-its-kind virtual research organization for supporting independent researchers (and academics thinking independently). You can read the announcement post to learn more about the motivation, philosophy, and structure of the Collective, but in brief we would like to offer researchers the following:

A title (SoS Research Fellow) and dedicated profile page

Payment of $50 per peer-reviewed article publishing in our journal

Editing and advising services

Promotion of your work on the SoS Substack.

Anyone conducting independent research (including undergraduate or graduate students conducting research activities outside of their primary academic work) who feels that they might benefit from being a SoS research fellow is welcome to apply. To apply, shoot us an email that tells us who you are and what your research is about—CV, website, blog, twitter, etc.—and we will go from there (info@theseedsofscience.org).

As I’ve said before, “I do not charge for any of this sizzling hot content and I never will. Paywalls cannot and should not contain the Bacon; Bacon is for the people, by the people”.

But the SoS Research Collective is going to cost money, and while I personally don’t need your filthy money, Seeds of Science would greatly appreciate it. So, if you’d like to support my work—the silly essays that I write, these links posts, all of the editing, curating, promotion, and recruitment I do for the the SoS journal and now the Collective—then there are two ways you can donate to the cause:

A paid subscription to the Seeds of Science Substack (see below for a list of most recent “Best of Science Blogging” posts).

What does a paid subscription get you?

Here’s the rub though—putting ideas (i.e. seeds of science) behind a paywall is sort of against our whole philosophy. So we aren’t going to do that. So what is a paid subscription getting you then? The sheer bliss that comes with knowing you are one of the good guys, that you stand on the right side of history, that your descendents will smile upon your deeds. What I’m really trying to say is that a subscription is really just a donation.

The whole selection is fantastic, esp. the artworks, thank you for sharing.

I've been thinking, particularly about the AI ones, perhaps that's its best application for it so far? I mean to produce visuals that are impossibly hard (or impossible) for a human to make by hand, something weird and unhinged?

Where’s no 8 from?