Japanese Death Poems (part 3)

by haiku poets

Although the consciousness of death is in most cultures very much a part of life, this is perhaps nowhere more true than in Japan, where the approach of death has given rise to a centuries-old tradition of writing jisei, or “death poems.” Such poems are often written in the very last moments of the poet’s life.

Hundreds of Japanese death poems, many with a commentary describing the circumstances of the poet’s death, are translated into English here, the great majority of them for the first time.

The following poems are selected from the second section of the book which features poems written by haiku poets. Enjoy.

Death poems by zen monks (part 1)

Death poems by haiku poets (part2)

1.

KYOHAKU (虚白)

Died on the last day of the 10th month, 1847 at the age of 75

I am not worthy

of this crimson carpet:

autumn maple leaves.

2.

KYO’ON (去音)

Died on the 10th day of the 11th month, 1749 at the age of 63

A last fart:

are these the leaves

of my dream, vainly falling?

In the original, the image of a dream is combined with the cruder image of passing wind. The transition from one to the other is made by a play on words: sharakusashi means “boastfulness” or “vanity”; the latter part of the word alone, kusashi, means “stench.”

3.

KYUTARO (久太郎)

Died on the 20th day of February, 1928 at the age of 36

Tender winds above the snow

melt many kinds

of suffering.

Kyutaro started working as a messenger boy for a commercial firm at the age of twelve. A year later, on Emperor’s Day (February 11) he went out to play in the snow. The head clerk considered such behavior an affront to the nation and scolded him. The thirteen-year-old Kyutaro wrote this poem:

In heavy snow

I clean forgot

to raise the nation’s flag.

In later years Kyutaro lived among workers and day laborers in Tokyo and became a radical anarchist. In 1923 he fired a gun at a government official and was sentenced to life imprisonment. He committed suicide in his cell, leaving his death poem behind him.

4.

MABUTSU (馬仏)

Died on the 21st day of the 12th month, 1696

The snowman’s eyes

are on the level; his nose

stands straight.

The snowman in this poem is not only a seasonal image, but also a symbol of transience.

Phrases such as “the eyes lie horizontally, the nose vertically” (given an alternate wording in the translation) and “the threshold is horizontal and vertical the pillar” appear in Zen writings as an expression of an enlightened point of view. Such remarks do not proceed from the understanding of any so-called truth, but from the reflection of the world in the consciousness that, like a clear mirror, has nothing in itself and neither adds to nor takes away from the thing it reflects.

5.

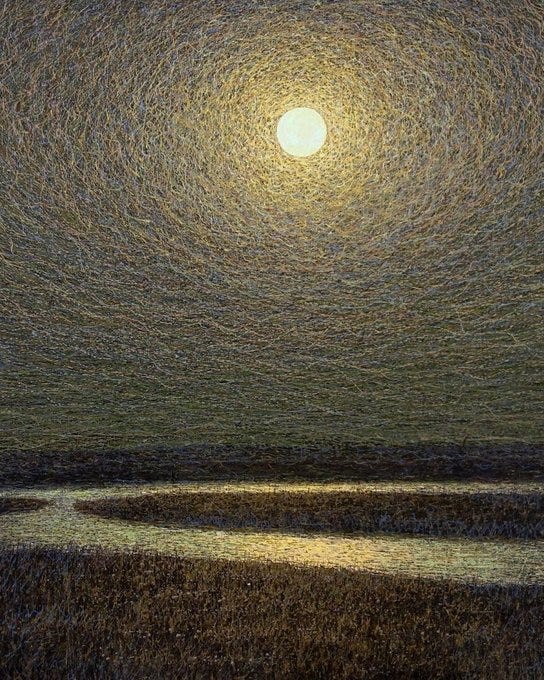

MASAHIDE (正秀)

Died on the 3rd day of the 8th month, 1723 at the age of 67

While I walk on

the moon keeps pace beside me:

friend in the water.

Masahide, a doctor by profession, lived most of his life in the town of Zeze on Lake Biwa. He studied haiku under Basho, whom he very much admired. Around 1688 Masahide’s storehouse burned down, and he wrote the following poem, which was much praised by Basho.

Now that my storehouse

has burned down, nothing

conceals the moon.

It seems that Masahide became very poor after his storehouse burned down. His poet friend Jozen, who came to visit him in 1103, reported that Masahide had no blanket for his two children, and had to cover them with mosquito netting.

6.

MOKUDO (木導)

Died on the 22nd day of the 6th month, 1723 at the age of 58

I constantly aspire

to be the first to pierce

my dagger in the eggplant.

Mokudo apparently tries, with the strange image of piercing a dagger into an eggplant (nasubi), to blend the fighting spirit (he belonged to the samurai class) with the spirit of haiku. The eggplant is a seasonal image for summer, during which the poet died; with a dagger stuck into it, the eggplant symbolizes the enemy’s head.

We are incorrect in hoping that the poem was written in jest, for the warrior-poet prefaces it with an explanation:

In times of war the samurai were the first to stab their daggers into their enemies. We are familiar with many stories about these bold warriors. Today peace reigns in the world and warriors no longer go forth into battle. They continue, however, with military exercises, so that in time of need they will be ready to fight zealously, till word of their courage echoes throughout Japan and the entire world.

7.

NAMAGUSAI TAZUKURI (腥斎佃)

Died on the 16th day of the 8th month, 1858 at the age of 72

In fall

the willow tree recalls

its bygone glory.

Namagusai Tazukuri, whose name means literally “peasant reeking of fish,” was born to a poor fishmonger. His parents died when he was young, and he was adopted by a fisherman. Namagusai Tazukuri was the fifth head of the senryū school.

8.

NANDAI (南台)

Died on the 24th day of the 12th month, 1817 at the age of 31

Since time began

the dead alone know peace.

Life is but melting snow.

9.

OKANO KIN’EMON KANEHIDE (岡野金右衛門包秀)

Died on the 4th day of the 2nd month, 1703 at the age of 24

Over the fields of

last night’s snow—

plum fragrance.

Okano Kin’emon Kanehide was one of the forty-seven samurai who participated in one of the most exciting incidents in Japanese history. In 1701, a feudal lord named Asano Nagamori was ordered to hold a reception in honor of the emperor’s messenger. A high official by the name of Kira Yoshinaka, who was appointed by the shogun to be in charge of ceremony, was to instruct Asano in ceremonial etiquette.

Kira treated Asano with contempt. Asano, his pride wounded, drew his sword and struck Kira. Since the incident took place in the castle at Edo, in the grounds of which the drawing of weapons was strictly forbidden, Asano was ordered to take his own life by seppuku on that very day. He did so. Asano’s estate was confiscated by the government, and the shogun rejected the petition brought to him by Asano’s retainers to hand over the estate to the younger brother of the deceased.

Thus Asano’s warriors became ronin, samurai without a lord. Forty-seven of them swore to avenge their master by killing Kira. To keep from attracting attention to themselves, they scattered to different parts of the country and waited for the proper moment. It came two years later, when Kira began to relax the security measures he had taken to protect himself. On a snowy morning of the 2nd month, 1702, the samurai broke into Kira’s mansion and killed him. They then turned themselves over to the government.

In taking their revenge, the forty-seven samurai acted in accordance with the moral code that forbade them to “live under the same sky as the enemy of their lord.” They gained sympathy in many circles of society, and the shogun himself was inclined to pardon them. In the end, however, those who insisted on enforcing the law prevailed, and a year after the incident took place, all forty-seven warriors were ordered to kill themselves by seppuku. This event excited the imagination of the Japanese, and the forty-seven samurai gained an immortal place in the history and the literature of their country.

10.

RAIZAN (来山)

Died on the 3rd day of the 10th month, 1716 at the age of 63

Farewell, sire—

like snow, from water come

to water gone.

Raizan, a contemporary of Basho’s, learned to write haiku at the age of eight and was authorized to teach and criticize haiku at the age of eighteen. It was said of Raizan that he never put his wine glass down and that he never stayed sober for so much as a day at a time. Rumor had it that he loved a doll rather than a woman and for that reason did not get married. In fact, he was married twice.

Just before his death, Raizan wrote a humorous death poem in tanka form:

Raizan has died

to pay for the mistake

of being born:

for this he blames no one,

and bears no grudge.

11.

RANDO (鸞動)

Died on the 30th day of the 7th month, 1686 at the age of 22

For a moment there

the ivy dyed

the evergreen trunk red.

The tsuta is a clinging vine found on stones and trees throughout Japan. Its leaves turn red before falling. The evergreen mentioned in the poem is the pine (matsu).

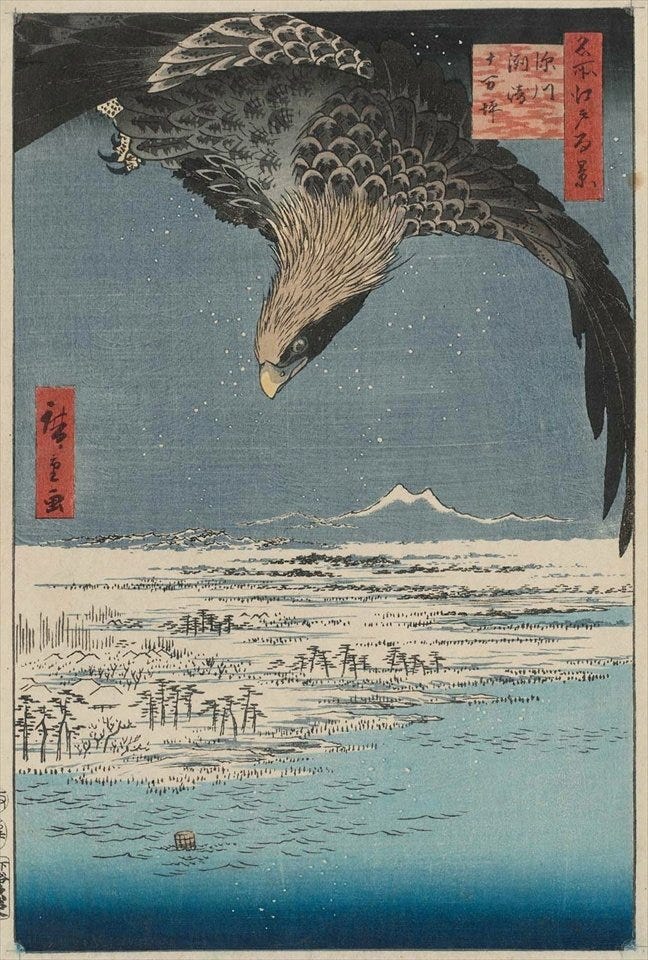

12.

RANGAI (嵐外)

Died on the 26th day of the 3rd month, 1845 at the age of 75

I wish to die

a sudden death with eyes

fixed on Mount Fuji.

13.

RETSUZAN (列山)

Died on the 25th day of the 8th month, 1826 at the age of 37

The night I understood

this is a world of dew,

I woke up from my sleep.

14.

ROKUSHI (六之)

Died on the 16th day of August, 1881 at the age of 75

I wake up

from a seventy-five-year dream

to millet porridge.

The poem alludes to a Chinese folktale about a man who dreamed that he rose in importance and became the holder of a wealthy estate. He woke up to discover that the millet porridge he had put on the fire had not yet boiled. The moral of the story is that visions of grandeur are vain, but it is tinged perhaps with a Zen Buddhist flavor as well: the truth we search for is to be found in the simple things before our eyes.

15.

RYUSHI (隆志)

Died on the 6th day of the 9th month, 1764 at the age of 70

Man is Buddha—

the day and I

grow dark as one.

16.

SARUO (猿男)

Died on the 27th day of April, 1923 at the age of 63

Cherry blossoms fall

on a half-eaten

dumpling.

A dango is a rice dumpling, sometimes filled with red-bean paste. One occasion for eating dango is during the cherry-blossom season in the spring. Hana no / wakare means literally “flower departure”; the expression can be taken to mean the parting between the onlooker and the blossoms. It is perhaps best, however, not to read the viewer into the poem at all, but to take it as the end of a scene in which only a half-eaten dumpling and falling blossoms are left on the stage.

17.

SEIJU (盛住)

Died on the 15th day of the 8th month, 1776 at the age of 75

Not even for a moment

do things stand still—witness

color in the trees.

18.

SHIYO (子葉)

Died on the 4th day of the 2nd month, 1703 at the age of 32

Surely there’s a teahouse

with a view of plum trees

on Death Mountain, too.

Shiyo (Otaka Gengo Tadao) was one of the forty-seven samurai who, in the winter of 1703, avenged the death of their master and who were thus ordered to commit seppuku as punishment. In Shiyo’s death poem, shide no yama, “mountain of death,” is the mountain crossed, according to the belief, in the journey from life to death.

It is recorded that Shiyo left another death poem in his last letter to his mother:

Snow on the pines

thus breaks the sword

that splits mountains.

19.

SHOFU (椎風)

Died on the 5th day of the 12th month, 1848 at the age of 57

One moon—

one me—

snow-covered field path.

20.

SHOGETSU (松月)

Died on the 2nd day of September, 1899 at the age of 70

Autumn ends:

frogs settle down

into the earth.

21.

SHOHI (松琵)

Died on the 14th day of the 8th month, 1750 at the age of 79

O morning glory—

I, too, yearn for

eternity.

Jūman’ōkudo is one of the names for paradise or the eternal; it means literally “the ten trillion land.” This might refer to the distance between paradise and this world, but it may also suggest infinite duration.

Although Shohi’s poem expresses a desire to abandon this world, it would seem that he was nevertheless quite interested in its phenomena. It is said that while Shohi was visiting the poet Rosen in the city of Nagoya during one of his journeys, he heard that an elephant was being shipped to the shogun in Edo. The fifty-seven-year-old poet became curious. He went forty miles out of his way, lodging overnight in a roadside inn and getting up at three in the morning, just to catch a glimpse of the animal.

22.

SHOKEI (松渓)

Died on the 13th day of February, 1895 at the age of 72

My shame in this world

will soon be forgotten—

springtime journey.

23.

SHUHO (舟甫)

Died in 1767

Cicada shell:

little did I know

it was my life.

24.

TADATOMO (忠知)

Died on the 27th day of the 11th month, 1676 at the age of 52

This frosty month

nought but the shadow

of my corpse remains.

Tadatomo committed suicide in the traditional Japanese manner. The reason for his suicide is not clear. Just before his death he wrote this death poem and added the words, “the vicissitudes of my life—how sad!”

Shimotsuki, “frost month,” is the name for the 11th month of the lunar calendar (by the solar calendar, approximately the month of January).

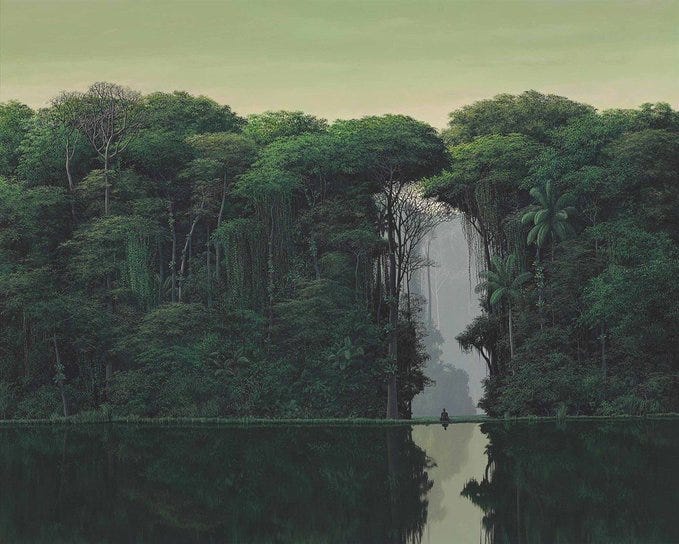

25.

TAMASHICHI (玉七)

Died in 1910

A lone monk

came to call

one autumn evening.

26.

TANEHIKO (種彦)

Died on the 13th day of the 7th month, 1842 at the age of 60

Cool—

a seagull suddenly

submerges.

27.

TANKO (旦葵)

Died in 1735(?) at the age of about 70

Today too,

melon-cool, the moon

comes up above the fields.

Life-cutting ax

lured by the hunter’s

deer call, a doe approaches.

The moon leaks out

from sleeves of cloud

and scatters shadows.

The first snow

falls upon the bowels

of Tombstone Mountain.

Tanko, one of Basho’s pupils, was a cake-seller and practitioner of acupuncture. Once a sack of grain was brought to Tanko as a present from one of his patients. Tanko was so delighted that he brought out a bottle of rice wine to celebrate the occasion. Just then a messenger came from the sender to inform him that a mistake had been made; the gift that was meant for Tanko was a sack of radishes, not of grain. Tanko was crestfallen. Later, however, when his poet-friend Etsujin came by, the two of them broke out laughing. On another occasion, during an acupuncture treatment, Tanko was unable to extract one of the needles from the body of his patient. Leaving the patient with the needle still in his flesh, he fled from the place.

We do not know when Tanko died. The poems were written a short time before his death, and the seasonal images belong to the time between autumn and winter. The “deer call” in the second poem refers to an instrument blown by hunters which imitates the mating call made by stags in autumn to attract does. Toribe-yama (fourth poem) is the name of a hill in Kyoto that has a cemetery on it.

28.

TOKO (杜口)

Died on the 11th day of the 2nd month, 1795 at the age of 86

Death poems

are mere delusion—

death is death.

29.

TOKUGEN (徳元)

Died on the 28th day of the 8th month, 1647 at the age of 89

My life was

lunacy until

this moonlit night.