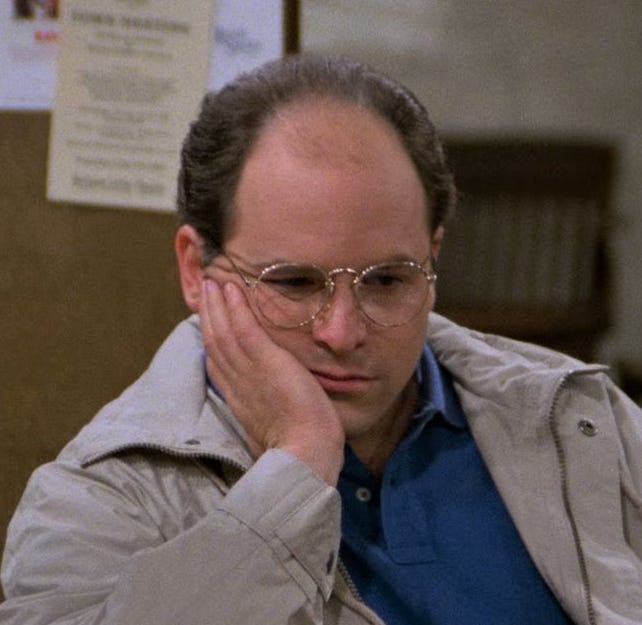

Human Sacrifice

...

It’s painful to confront how limited your time is, because it means that tough choices are inevitable and that you won't have time for all you once dreamed you might do. It’s also painful to accept your limited control over the time you do get: maybe you simply lack the stamina or talent or other resources to perform well in all the roles you feel you should. And so, rather than face our limitations, we engage in avoidance strategies, in an effort to carry on feeling limitless. We push ourselves harder, chasing fantasies of the perfect work-life balance; or we implement time management systems that promise to make time for everything, so that tough choices won’t be required. Or we procrastinate, which is another means of maintaining the feeling of omnipotent control over life—because you needn’t risk the upsetting experience of failing at an intimidating project, obviously, if you never even start it. We fill our minds with busyness and distraction to numb ourselves emotionally, or we plan compulsively, because the alternative is to confront how little control over the future we really have. Moreover, most of us seek a specifically individualistic kind of mastery over time—our culture’s ideal is that you alone should control your schedule, doing whatever you prefer, whenever you want—because it's scary to confront the truth that almost everything worth doing, from marriage and parenting to business or politics, depends on cooperating with others, and therefore on exposing yourself to the emotional uncertainties of relationships.

Denying reality never works, though. It may provide some immediate relief, because it allows you to go on thinking that at some point in the future you might, at last, feel totally in control. But it can’t ever bring the sense that you’re doing enough—that you are enough—because it defines “enough” as a kind of limitless control that no human can attain. Instead, the endless struggle leads to more anxiety and a less fulfilling life.

All of this illustrates what might be termed the paradox of limitation, which runs through everything that follows: the more you try to manage and master your time with the goal of liberating yourself from the inevitable constraints of being human, the more stressful, empty, and frustrating life gets. But the more you confront the facts of finitude instead—and work with them, rather than against them—the more productive, meaningful, and joyful life becomes. I don’t think the feeling of anxiety ever completely goes away; we’re even limited, apparently, in our capacity to embrace our limitations…

In practical terms, a limit-embracing attitude to time means organizing your days with the understanding that you definitely won't have time for everything you want to do, or that other people want you to do—and so, at the very least, you can stop beating yourself up for failing. Since hard choices are unavoidable, what matters is learning to make them consciously, deciding what to focus on and what to neglect, rather than letting them get made by default—or deceiving yourself that, with enough hard work and the right time management tricks, you might not have to make them at all. It also means resisting the seductive temptation to “keep your options open”—which is really just another way of trying to feel in control—in favor of deliberately making big, daunting, irreversible commitments, which you can't know in advance will turn out for the best, but which reliably prove more fulfilling in the end. And it means standing firm in the face of FOMO, the “fear of missing out,” because you come to realize that missing out on something—indeed, on almost everything—is basically guaranteed. Which isn’t actually a problem anyway, it turns out, because “missing out” is what makes our choices meaningful in the first place. Every decision to use a portion of time on anything represents the sacrifice of all the other ways in which you could have spent that time, but didn’t—and to willingly make that sacrifice is to take a stand, without reservation, on what matters most to you.1

As theurgists were purified and developed a greater capacity to receive divine light, they would enter a deeper dimension of sacrifice, one revealed in the altar itself. They would realize that their sacrifice of mortal life to the gods had been, all along, an inverse reflection of the gods’ prior sacrifice to the world of generation, specifically the sacrifice of immortality to mortal life: taking the form of the human body, the bômiskos. It is then that the theurgist would experience the depth of his paradox: he is the mortal being that offers sacrifices to the gods while, at the same time, he is the god that sacrifices its divinity on the altar of the human body. Through the altar the theurgist offers himself to himself: as man to god and as god to man; he discovers his divinity through his mortality and enters a circulation whose pivotal point of return is the bômiskos, the sacrificial body-altar.2

In any situation, any decision I make is already radically limited. For one thing, it’s limited in a retrospective sense, because I’m already who I am and where I am, which determines what possibilities are open to me. But it’s also radically limited in a forward-looking sense, too, not least because a decision to do any given thing will automatically mean sacrificing an infinite number of potential alternative paths. As I make hundreds of small choices throughout the day, I’m building a life—but at one and the same time, I’m closing off the possibility of countless others, forever. (The original Latin word for “decide,” decidere, means “to cut off,” as in slicing away alternatives; it’s a close cousin of words like “homicide” and “suicide.”) Any finite life—even the best one you could possibly imagine—is therefore a matter of ceaselessly waving goodbye to possibility.3

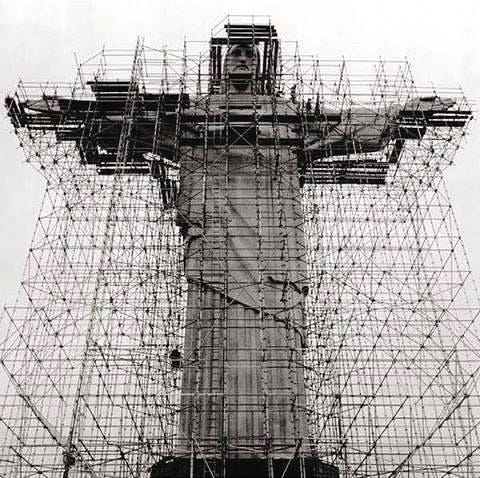

We are all hanging from the cross of spacetime. His divine nature is our true nature: timeless Mind incarnating as a mortal being within its own Dream. Christ, both God and the Son of God born into His own creation—the symbolism could hardly be more direct.4

Is it true that one really lives on the earth?

Not forever on earth, only here a little while.

Though it be jade, it breaks apart.

Though it be gold, it wears away.

Though it be quetzal feather, it is torn asunder.

Not forever on earth, only here a little while.

Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals by Oliver Burkeman

“The Sphere and the Altar of Sacrifice” by Gregory Shaw (2005)

ibid, Oliver Burkeman

Bernardo Kastrup, with slight modification

Well said. Decisions are hard. I think ultimately we humans may need some mythos or fiction that things will work out, at least at the early levels.

I don’t quite get the stuff about gods becoming man but hey I’m a Christian so you know I love it. ;)

You think it's bad in middle age, wait until you are truly old.