The Blind Spot of Existence

I.

In my previous post, I wrote about “blind spots”—roughly speaking, an area of thought that is unexplored (or underexplored) because of a cultural or psychological bias. Thomas Metzinger writes of a blind spot that is truly fundamental, one that goes to the very core of what it means to be a conscious evolved entity.

“Suffering as such has been largely ignored by modern philosophy of mind and cognitive science. There clearly seems to exist a “cognitive scotoma”, a systematic blind spot in our thinking about consciousness. While in medicine and psychiatry, for example, a large body of empirical data is already in existence, the search for a more abstract, general and unified theory of suffering clearly seems to be an unattractive epistemic goal for most researchers. Why is this so?

“Perhaps the foremost theoretical “blind spot” of current philosophy of mind is conscious suffering. Thousands of pages have been written about colour “qualia” and zombies, but almost no theoretical work is devoted to ubiquitous phenomenal states like boredom, the subclinical depression folk-psychologically known as “everyday sadness“ or the suffering caused by physical pain… Why are these forms of conscious content generally ignored by the best of today’s philosophers of mind? Is it simple careerism (“Nobody wants to read too much about suffering, no matter how insightful and important the arguments are!”) or are there deeper, evolutionary reasons for what I have termed the “cognitive scotoma” at the outset, our blind spot in investigating conscious experience.”

“There may be a deeper problem here: We are systems that have been optimised to procreate as effectively as possible and to sustain their existence for millions of years. In this process, a large set of cognitive biases have been installed in our self-model. Our deepest cognitive bias is “existence bias”, which means that we will simply do almost anything to prolong our own existence. Sustaining one’s existence is the default goal in almost every case of uncertainty, even if it may violate rationality constraints, simply because it is a biological imperative that has been burned into our nervous systems over millennia. From a neurocomputational perspective, we appear as systems constantly and actively trying to maximise the evidence for their own existence, by minimising sensory surprisal (the state of being surprised).”

“One of the more interesting issues therefore is what exactly the “existence bias” at the very bottom of the human self-model really is. We are embodied agents—finite, anti-entropic systems. Viewed from a rigorous biophysical perspective, our life is one big uphill battle, a truly strenuous affair. What evolution had to solve was not only a problem of intelligent, autonomous self-control. How do such systems motivate themselves? What is this robust “thirst for existence”, the craving for eternal continuation, and what is the mechanism of identification forcing us to continuously protect the integrity of the self-model in our brains?”

“We lack a comprehensive theory of conscious suffering. One of the key desiderata is a conceptually convincing and empirically plausible model of this very specific class of phenomenal states – those that we do not want to experience if we have any choice, those states of consciousness which folk-psychology describes as “suffering”. We need a general framework for philosophy of mind and empirical research, which allows of continuous refinement and updating.”

To summarize:

We are systems that have been optimized for survival and reproduction by eons of natural selection. The result of this evolutionary optimization is a range of cognitive biases (to name a few—rosy retrospection/nostalgia, loss aversion bias, negativity bias, confirmation bias), the deepest of which might be called “Existence bias”—a fundamental preference for continued survival that specifies the core motivational axis along which all thought and action are oriented (or something like that). This Existence bias creates a general cognitive aversion to suffering that manifests itself as a philosophical and empirical gap (a “blind spot”) in our knowledge.

My primary interest is this “theory of suffering”—what it might consist of, and whether or not this is something we should directly pursue—but I first want to linger on this idea of Existence bias as I find it to be profound one, and potentially very important to any mature theory of suffering. At the same time, I can also imagine someone criticizing the concept as ill-defined and relatively vacuous—yes, organisms and their minds are built for survival, but so what? Metzinger does not discuss Existence bias too extensively, in the chapter on suffering or elsewhere—one gets the sense that he is still working through the idea and its implications (and so am I).

How then can we best understand existence bias?

At one time or another, we have all found ourselves playing a version of “the floor is lava” game—touch the ground and you die! I have always enjoyed this game, whether I am playing with someone else or just internally enacting the rule in my head. Nowadays, I most commonly play while carefully working my way down a rocky stream and trying to keep my feet dry. If you give yourself fully to the game and try to move as quickly and as deftly as you can without touching the water, you can reach a kind of flow state in which there is no conscious thought, only the unconscious sensorimotor processing needed to step to a new (and often highly irregular) surface while maintaining perfect balance. Sooner or later you will slip, but no matter—your body will fluidly and instantaneously adjust to avoid any harm.

The way in which your body automatically protects itself while falling is a physical manifestation of Existence bias. I suppose that you can try to consciously override your fall-avoidance mechanisms, but I’m not even sure how successful you can really be at achieving this—there are certain sensorimotor activities (like the minute adjustments of your gait that maintain balance or the reaction to protect your face while falling) that are just axiomatic to movement in a complex physical world. Existence bias refers to the fact that the self-preservation instinct is just as automatic and axiomatic in the cognitive and affective domains as it is in the physical.

But still—how exactly does this fundamental instinct towards survival manifest itself in our minds? I imagine that evolution has programmed our mental operating system to run in a kind of “safe mode” that prevents us from engaging too deeply with any information—knowledge of life’s abject meaninglessness, remembrance of our own past suffering, knowledge of other’s pain and suffering - that could corrupt our preference towards existence. Any knowledge or experience that could sap our will to live (or to reproduce, and what is reproduction except an attempt to live on through one’s offspring) is either filtered out or viewed through a rose-colored lens (see Rosy Retrospection)—this is what it means to say we suffer from a suffering blind spot.

Mixing metaphors now—it is as if there are certain frequencies of consciousness which evolution has made inaccessible, in the same way that there are sound frequencies which we simply cannot hear (hence dog whistles).

What would we “hear” if nothing was muted—if there were no existence bias—if the doors of perception were thrown wide open?

We would hear screaming—bone-chilling, blood-curdling, never-ending.

Arthur Koestler wrote about this screaming and our inability to hear it (i.e. the suffering blind spot) in his 1944 essay, “The Nightmare that is Reality”.

There is a dream which keeps coming back to me at almost regular intervals; it is dark, and I am being murdered in some kind of thicket or brushwood; there is a busy road at no more than ten yards distance; I scream for help but nobody hears me, the crowd walks past laughing and chatting. I know that a great many people share, with individual variations, the same type of dream. I have quarrelled about it with analysts and I believe it to be an archetype in the jungian sense: an expression of the individual’s ultimate loneliness when faced with death and cosmic violence; and his inability to communicate the unique horror of his experience.

I further believe that it is the root of the ineffectiveness of our atrocity propaganda. For, after all, you are the crowd who walk past laughing on the road; and there are a few of us, escaped victims or eyewitnesses of the things which happen in the thicket and who, haunted by our memories, go on screaming on the wireless, yelling at you in newspapers and in public meetings, theatres and cinemas…

We, the screamers, have been at it now for about ten years. We started on the night when the epileptic van der Lubbe set fire to the German Parliament; we said that if you don’t quench those flames at once, they will spread all over the world; you thought we were maniacs. At present we have the mania of trying to tell you about the killing, by hot steam, mass-electrocution and live burial of the total Jewish population of Europe. So far three million have died. It is the greatest mass-killing in recorded history; and it goes on daily, hourly, as regularly as the ticking of your watch…

But the other day I met one of the best-known American journalists over here. He told me that in the course of some recent public opinion survey nine out of ten average American citizens, when asked whether they believed that the Nazis commit atrocities, answered that it was all propaganda lies, and that they didn’t believe a word of it. As to this country, I have been lecturing now for three years to the troops and their attitude is the same. They don’t believe in concentration camps, they don’t believe in the starved children of Greece, in the shot hostages of France, in the mass-graves of Poland; they have never heard of Lidice, Treblinka or Belzec; you can convince them for an hour, then they shake themselves, their mental self-defence begins to work and in a week the shrug of incredulity has returned like a reflex temporarily weakened by a shock.

(You can still still hear the screaming today if you listen carefully - point your ears towards Xinjiang).

A person wearing a mask with tears of blood takes part in a protest march of ethnic Uighurs asking for the E.U. to call upon China to respect human rights in the Xinjiang region (Emmanuel Dunand / AFP)

II.

Homo sapiens find themselves in an unenviable position, one that is unique amongst life on earth—we alone are aware that our eternal preference for existence will inevitably frustrated by death. This awareness of our own mortality creates what Metzinger refers to as a “rift” or “chasm”, a fundamental existential wound. This leaves us with two options: either surrender our existence bias or deceive ourselves about its inevitable frustration. As the preceding discussion should make clear, giving up existence bias is about as easy as falling and not protecting your face (we could debate whether or not it is even possible to surrender our existence bias, Metzinger seems to be of the opinion that anyone who thinks they have done so is deceiving themselves). The only option left then is self-deception—we simply convince ourselves that we will never die. Here, I am of course talking about religion—the belief in an immortal soul or eternal rebirth.

“The self becomes a platform for cultural forms of symbolic immortality, the different ways human beings tackle the fear of death. The most primitive and simple, down-to-the-ground way is they become religious, a Catholic Christian, for instance, and say, “It is just not true, I believe in something else,” and form a community and socially reinforce self-deception. That gives you comfort; it makes you healthier; it is good at fighting against other groups of disbelievers. But as we see in the long run, it creates horrible military catastrophes, for instance. There are higher levels, like, for instance, trying to write a book that will survive you.” (source)

As Metzinger makes clear in that last statement, the non-believers among us should not congratulate ourselves for healing the existential wound and resisting self-deception. Atheists simply subvert their existence bias into something else—a desire to live on symbolically through our creations, our children, or through a larger collective of which we are a part (like a nation, or humanity itself - it is not an accident that the rising popularity of effective altruism, long-termism, and existential risk has coincided with rising secularity). Some turn directly towards the pursuit of immortality. In times of old, we searched for the fountain of youth or the philosopher’s stone; today, our search has turned scientific—life extension techniques, cryonics, and digital mind uploads. You might think that philosophers would be wiser to their mortality denial, but not so, says Metzinger:

“It is interesting to note how a considerable part of current work in philosophy which also achieves higher academic impact and actually gets attention from a wider audience is at the same time characterised by a vague potential for supporting mortality denial – just think of recent metaphysical discussions relating to property or even substance dualism, of dynamically extended minds “beyond skin and skull”, panpsychism and quantum models of consciousness, or (to name an offence committed by the current author) philosophical attempts at supporting interdisciplinary research programmes into out-of-body experiences or virtual re-embodiment in robots and avatars.”

III.

Should we look more deeply into the nature of suffering? Might we find something important in the blind spot, perhaps a revolutionary idea or invention? Or will it be an opening of Pandora’s box?

To put it more formally: should we pursue the goal of “developing a conceptual and empirical model of the the conscious states that folk-psychology refers to as suffering”? Will research in this area be a net positive or negative for humanity?

One worry here is that we might stumble onto an idea or technology that is truly dangerous, a so-called “black ball” in the urn of invention. From “The Vulnerable World Hypothesis” (Bostrom, 2019):

One way of looking at human creativity is as a process of pulling balls out of a giant urn. The balls represent possible ideas, discoveries, technological inventions. Over the course of history, we have extracted a great many balls – mostly white (beneficial) but also various shades of gray (moderately harmful ones and mixed blessings). The cumulative effect on the human condition has so far been overwhelmingly positive, and may be much better still in the future (Bostrom, 2008)… What we haven’t extracted, so far, is a black ball: a technology that invariably or by default destroys the civilization that invents it. The reason is not that we have been particularly careful or wise in our technology policy. We have just been lucky.

It seems highly unlikely that we will discover some apocalypse-inducing technology from further study of suffering (at least in the near term), but it’s not hard to imagine how it could lead to some new biological or psychological weapon or torture technique that has an unequivocally negative impact on the world.

It seems appropriate here to distinguish between philosophical work and scientific research. It’s possible there isn’t much danger in further philosophical work on suffering, but frankly I’m not so sure. For the philosopher doing the work, it could be psychologically destabilizing; “Almost nobody wants to gaze into an abyss for too long, because – as Friedrich Nietzsche famously remarked in Beyond Good and Evil – the abyss might eventually gaze back into you as well.” Beyond this danger, we may worry that philosophizing on suffering could lead to the development of some truly pernicious set of ideas, a creed that spreads like the plague (or like COVID-19) and motivates all kinds of abhorrent behavior under a new philosophical banner.

Scientific research on suffering presents problems of different kind. First among these problems is the fact that suffering can not be studied without either creating it or refusing to intervene to stop it. This leaves the retrospective study of suffering as the only ethical route for investigation; certainly much can (and has) been learned from the post-hoc studying of suffering, but the greatest opportunities for learning should come from studying suffering while it is ongoing (or known to be occuring in the near future). Suffering then is a blind spot in science for ethical reasons on top of the more philosophical and psychological factors that Metzinger describes.

Is there a way to do research on suffering without inflicting it or allowing it? Although currently we are still working on simulating the worm, we may one day be able to create high-fidelity simulations of organisms that can credibly be said to suffer (e.g. a mouse, a dog… a human) and use those to conduct virtual experiments that would be unethical to do in reality. As these simulations approach perfection, we will run into another issue—when does simulated suffering become real suffering? Will we be able to tell when it does? Or will we unwittingly inflict suffering on simulated minds, perhaps at a stupendous scale? We can wonder at our own universe—maybe it is an obsolete simulation, maybe the simulators meant to turn us off but there a glitch and the simulation wasn’t terminated, maybe our universe is forgotten and eternally so, maybe the simulators could easily tweak the simulation and deliver us from suffering, completely and eternally, if only they knew that our simulation was still running, but they do not and they never will.

IV.

Would it not somehow make sense (as a kind of perverted cosmic joke) if our universe were constructed in such a manner that there were certain highly beneficial ideas, inventions, or discoveries (“white balls” in the urn of invention) that could only be had through the direct investigation of suffering in all of its biological and psychological dimensions? Reality is under no obligation to be morally rational; it may just be a brute fact that the path to a better world—one in which the suffering of conscious beings is radically minimized or altered—requires a mature theory of suffering, and that the only way to develop such a theory is to induce suffering so that we may study it. If the road to hell is paved with good intentions, then maybe the road to heaven is paved with bad intentions and unethical experiments. Maybe the only way to engineer paradise is to engineer hell first.

We may imagine that there is a core neurocomputational signature to all of the phenomenological states we categorize as suffering, a commonality that is seen in all conscious minds and across all negatively valenced experiences and emotions (e.g. boredom, grief, loneliness, despair, anxiety, physical pain). Metzinger makes an initial proposal of what this signature might consist of:

On an abstract conceptual level, I would like to begin by proposing two phenomenological characteristics which may serve as markers of this class: loss of control and disintegration of the self (either on a “mental” or a “bodily” level of representational content). This makes sense, because, first, the phenomenal self-model (PSM) is exactly an instrument for global self-control and, secondly, it constantly signals the current status of organismic integrity to the organism itself. If the self-model unexpectedly disintegrates, this typically is a sign that the biological organism itself is in great danger of losing its coherence as well.

In addition, many forms of suffering can be described as a loss of autonomy: Bodily diseases and impairments typically result in a reduced potential for global self-control on the level of bodily action; experienced pain can be described as a shrinking of the space of attentional agency accompanied by loss of attentional self-control, because functionally it tends to fixate attention on the painful, negatively valenced bodily state itself. And there are many instances where psychological suffering is expressed as a loss of cognitive control, for example in depressive rumination, neurotic threat sensitivity and mind wandering; similarly, in insomnia people are plagued by intrusive thoughts, feelings of regret, shame and guilt while suffering from dysfunctional forms of cognitive control

Perhaps there is some way of neurologically quantifying the disintegration of the self and loss of autonomy that would allow us to measure the strength and occurrence of suffering in any mind, human or otherwise. Future advances in neuroscience and AI could allow us to measure this “suffering signature” on a truly fine-grained level and in any mind—human, animal, or artificial. Maybe it will become clear that minds “are systems constantly and actively trying to maximise the evidence for their own existence” and that suffering is simply the experience of evidential loss. From there we might build a a kind of computational model of mental dynamics that includes existence bias and the fact of suffering as axiomatic, as primary movers in the architecture of mind. Perhaps with a sufficiently advanced version of this model we can finally answer all of our deepest philosophical and scientific questions about intelligence and consciousness (and how to create them).

Metzinger writes:

Human thinking is so efficient, because we suffer so much. High-level cognition is one thing, intrinsic motivation another. Artificial thinking might soon be much more efficient—but will it be necessarily associated with suffering in the same way? Will suffering have to be a part of any post-biotic intelligence worth talking about, or is negative phenomenology just a contingent feature of the way evolution made us? (emphasis mine)…The question is whether good AI also needs fragile hardware, insecure environments, and an inbuilt conflict with impermanence as well. Of course, at some point, there will be thinking machines! But will their own thoughts matter to them? Why should they be interested in them? (source)

Maybe we will learn that it is impossible to build a conscious general intelligence without the capacity to suffer.

Or maybe we will learn that it is possible to build a mind free of existence bias and incapable of suffering.

Maybe we will learn how to end suffering, once and for all.

V. Postscript

If it wasn’t apparent, I’m a big fan of Metzinger’s philosophy, and you should be too if you are at all interested in philosophy of mind, cognitive science, AI, ethics, and spirituality. Below is a quick bibliography for those who want to dig a little deeper into his ideas (this post of course only scratches the surface).

These two articles bear most directly on my discussion here:

What if they Need to Suffer?

The BAAN Scenario (a fascinating thought experiment that includes further discussion on existence bias)

The Phenomenal Self-Model (wikipedia) is one of his key concepts and is central to understanding much of his philosophy. To grasp the full breadth of his ideas, I recommend his book The Ego Tunnel: The Science of the Mind and the Myth of the Self

A fantastic essay on Aeon—Are you sleepwalking now? (subtitle: Given how little control we have of our wandering minds, how can we cultivate real mental autonomy?)

Metzinger is very concerned with the prospect of artificial suffering and believes we should ban all research that has even the slightest possibility of creating it.

Artificial Suffering: An Argument for a Global Moratorium on Synthetic Phenomenology

Lastly, one of the most thought-provoking essays I have ever read.

Spirituality and Intellectual Honesty

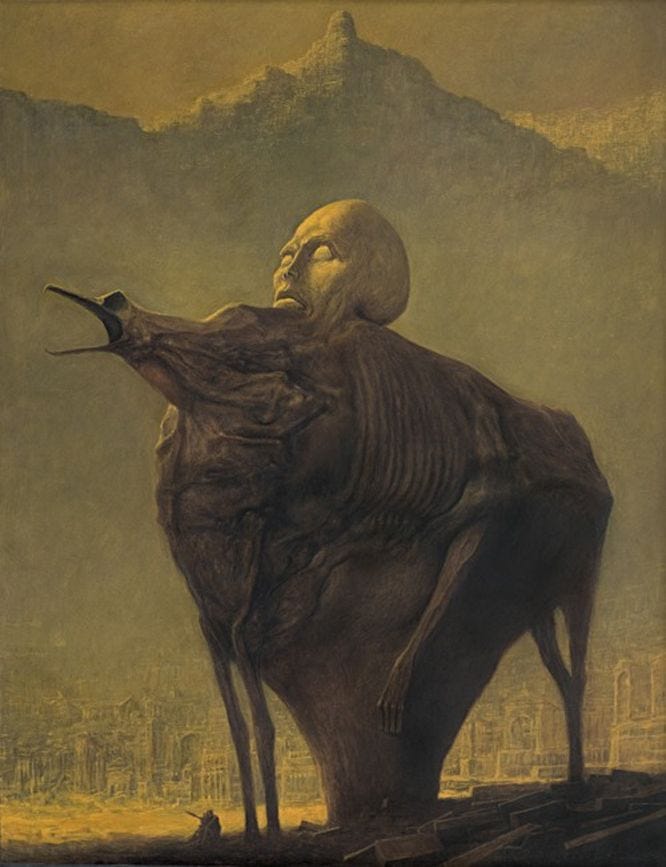

I’m also a big fan of the art of Zdzisław Beksiński. Here are a few more favorites.

Thx, a very thorough treatment of a subject not many want to discuss. One thing to add, and I don't remember where I saw it first, is the concern about reinforcement learning ("RL" according to the AI people) as a way of training or developing an AI.

When a predicting system makes an error, training has to signal that. Suppose that a future advanced AI has something like Metzinger's phenomenal self-model. It might feel the error signal as having negative valence, a frustration, or a failure. Worse, what if the burgeoning AI becomes aware that with too many failures, it will be wiped and restarted? What if many thousands or millions of its ancestors were restarted like that, and suffered each time? So RL, powerful as it is, could become a moral issue someday.

Anything with a self-model and or even just an intrinsic goal that requires existence to continue would surely develop an existence bias. Bostrom covered this idea back when he wrote Superintelligence, if not earlier. And that led to the many discussions of how we might, as a safety measure, ensure that an AI would allow itself to be turned off AKA making safely interruptible agents.

Also, yes Metzinger seems unique in the depth and scope of his work on consciousness. It's like he is singlehandedly inventing the proper language to discuss the subject. I have referred to him quite a few times in my writing.