There is an asymmetry between good and evil, an inequality between the two that belies their opposing nature.

Evil is never radical, it is only extreme, possessing neither depth nor any demonic dimension. It is ‘thought-defying’ because thought tries to reach some depth, to go to the roots, and the moment it concerns itself with evil, it is frustrated because there is nothing. That is its ‘banality.’ Only the good has depth that can be radical. (Hannah Arendt)

Imaginary evil is romantic and varied; real evil is gloomy, monotonous, barren, boring. Imaginary good is boring; real good is always new, marvelous, intoxicating. (Simone Weil)

Tolkien saw another aspect of the Asymmetry. Good can imagine becoming evil—hence Gandalf and Aragorn refusing the Ring—but evil, defiantly chosen, can no longer imagine anything but itself. Sauron cannot conceive of motives beyond domination and fear, so when he learns his enemies possess the Ring, the thought that they might destroy it never enters his head.

C.S. Lewis saw how the Asymmetry ripples through time:

That is what mortals misunderstand. They say of some temporal suffering, “No future bliss can make up for it,” not knowing that Heaven, once attained, will work backwards and turn even that agony into a glory. And of some sinful pleasure they say “Let me have but this and I’ll take the consequences”: dreaming little of how damnation will spread back and back into their past and contaminate the pleasure of the sin. Both processes begin even before death. The good man’s past begins to change so that his forgiven sins and remembered sorrows take on the quality of Heaven: the bad man’s past already conforms to his badness and is filled only with dreariness. And that is why, at the end of all things, when the sun rises here and the twilight turns to blackness down there, the Blessed will say “We have never lived anywhere except in Heaven,” and the Lost, “We were always in Hell.” And both will speak truly.

Four witnesses to the same brute existential fact: evil is shallow and static, unimaginative and impoverishing, while goodness possesses depth, creativity, dynamism. But why? Is there a way to explain or articulate the logic of the Asymmetry, to show why good necessarily exceeds evil in depth and complexity?

I would like to offer an answer drawn from an unlikely source. “Biology, Buddhism, and AI: Care as the Driver of Intelligence” (Doctor et al., 2022) provides, almost inadvertently, a formal structure that explains the Asymmetry.

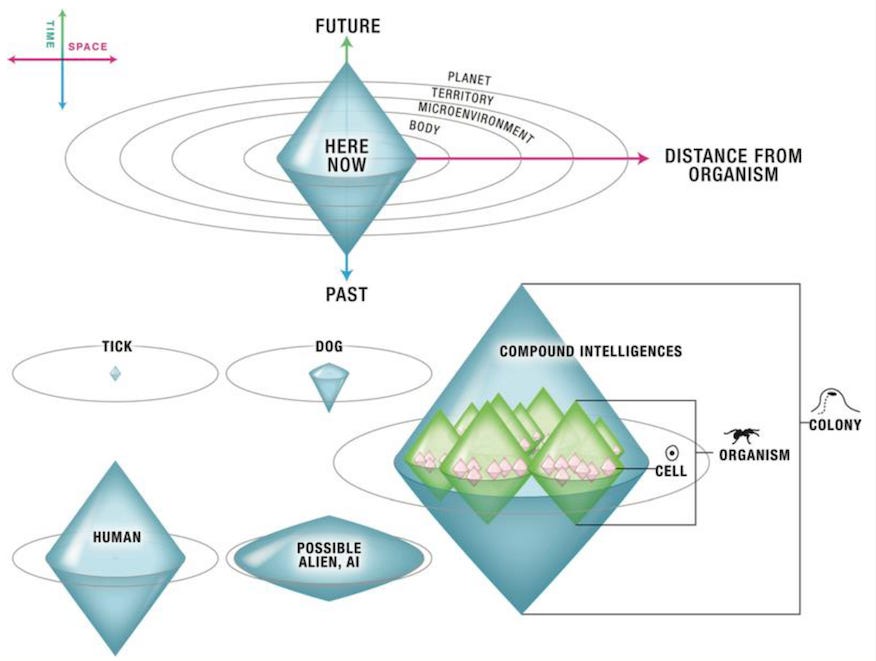

The foundational concept of the article is what the authors call the “cognitive light cone”—the outer boundary, in space and time, of the largest goal a given system can work toward. All intelligences, regardless of embodiment, can be mapped according to the scale of goals they can pursue. A bacterium navigates chemical gradients in its immediate environment; a human plans for retirement; a corporation optimizes across continents and generations.

All intelligences, no matter how embodied, can be compared directly with respect to the maximum spatiotemporal scale of the goals towards which they can represent and work. A corollary to this view is that the driver of this kind of homeostatic dynamic is that such systems exhibit “stress” (the delta between current state and optimal state, or the difference between the goals at different subsystems’ levels): reduction of this stress parameter is a driver that keeps the system exerting energy in action to move and navigate within the problem space.

When a system begins to include others’ stress within its own homeostatic loops—when it starts treating others’ suffering as its own problem to solve—its cognitive boundary necessarily expands. Care, in this framework, is not merely an emotion but a driver of intelligence itself. The more you can care about, the more you can think about, and the more you can do.

In this framework, the recognition of agency outside oneself and the progressive inclusion of their states in one’s own homeostatic stress-reduction loops is a bidirectional feedback loop that leads to the scaling of intelligence and increases in practical compassion. This loop operates on both the evolutionary and individual lifespan time scales, and in more advanced forms, comes under rational control of systems whose primary goals may start to include the meta-cognitive goal of increasing intelligence and compassion.

This brings us to the Bodhisattva.

The Bodhisattva vow is a commitment to pursue awakening for the benefit of all sentient beings throughout space and time:

Sentient beings are numberless; I vow to liberate them.

Delusions are inexhaustible; I vow to end them.

Reality is boundless; I vow to perceive it.

The awakened way is unsurpassable; I vow to embody it.

In terms of the cognitive light cone, this vow represents something unprecedented: the deliberate expansion of one’s boundary of concern to infinity. The Bodhisattva commits to knowing and responding to the needs of all beings, not as an abstraction but as an active project requiring, in principle, omniscience.

Now compare this to its apparent mirror image: “I shall subjugate everyone in time and space for my own pleasure.” At first glance, both commitments seem universal in scope. Both claim infinity. And yet…

In the case of the vow to subjugate for personal enjoyment, the universal commitment is directed toward the fulfillment of the agent’s individual version of what should be the case. Personal needs are intrinsically limited. Even though greed may feel infinite, once we begin to specify what we want, our needs become rather limited and predictable, because they largely correspond with our understanding of who and what we are... So despite the apparent grand scale, the drive toward “all my personal wishes” becomes quite trivial when compared to the care drive of a Bodhisattva.

This is the key to the Asymmetry. The selfish vow appears infinite but is finite, because it aims only at satisfying a single set of preferences—and preferences, however grandiose, are bounded by the self that holds them. Even “I shall make everything in time and space my personal property” remains confined to what I can want, which is limited by what I am.

The Bodhisattva’s vow is actually infinite because its scope is defined not by one mind but by the infinity of living beings, each with their own needs and desires across all of time and space. The Bodhisattva promises to know all of those needs and respond creatively to each. The paths and end states of universal compassion are genuinely inexhaustible; the paths and end states of universal domination are not.

In short, wherever the endless myriads of beings may find themselves, the Bodhisattva forms the intention to go there and effect positive change. Implicitly, this programmatic intention thus also contains an open-ended pledge to comprehend the past, because the ability to skillfully influence events in the present and future can be seen to involve knowledge of past states of affairs. Thus, by simply committing to the Bodhisattva stance and practices, the sphere of measurement and activity of the cognitive system that makes the commitment has gone from finite to infinite, and so the cone structure that otherwise is applicable to all forms of cognizant life has in this sense been transcended. Seeking to indicate infinity on both the spatial and temporal axes, we might now instead see the Bodhisattva cognitive system’s computational surface represented by an all-encompassing sphere that accommodates all instances of life within it…

This is why evil is boring, not as a moral judgment but as a structural fact. Evil contracts the light cone toward a single point, whereas goodness can expand it without limit.

But what about evil that isn’t selfish? Buddhism has a notion of this: Māra, the embodiment of pure malevolence. Māra, the so-called Buddhist devil, has no personal desires, no preferences to satisfy; its drive is entirely other-directed: “Wherever there are beings, let me prevent their awakening.” Here, it seems, is an evil that matches the Bodhisattva’s universal scope, a dark mirror of infinite compassion.

And yet the Asymmetry holds even here. Look closely at what Māra wants: for things to stay as they are. Beings suffer, and they shall keep suffering. It is a vow of cosmic preservation. The Bodhisattva, by contrast, commits to infinite transformation—to meeting each being in their particularity and drawing them toward flourishing. Māra’s universe is frozen; the Bodhisattva’s is endlessly alive.

And so even when evil sheds every trace of selfishness, even when it achieves universal scope, it remains essentially static. It can negate, prevent, maintain, but it cannot create. Goodness, and goodness alone, is generative. Evil is not the opposite of good in the way that cold is the opposite of heat. It is an absence, a refusal, a contraction away from the infinite fecundity of Being.

The Experience of God

There’s one thing that confuses me about all of this.

…The Bodhisattva vow can be seen as a method for control that is in alignment with, and informed by, the understanding that singular and enduring control agents do not actually exist. To see that, it is useful to consider what it might be like to have the freedom to control what thought one had next. Would not perfect control of one’s mind imply that one knew exactly what one was going to think, and then subsequently thought it? In that case, whenever a new thought arose, we would, absurdly, be rethinking what we had thought already, or otherwise there would, just as absurdly, have to be an infinite line of prior control modules in place for a single controlled thought to occur. Such consequences suggest that the concept of individual mind control is incoherent. “In control of my mind” (a necessary aspect of the common notion of free will) is logically impossible on the short time scale, but may be coherent on a very long time scale (“I’ve undertaken practices to eventually change the statistical distribution of the kinds of thoughts I will have in the future”).

So if agents don’t really exist, if there are no selves in control of anything, who is making the Bodhisattva vow? If no one exists, who is there to care for? And who is there to do the caring?

There is no one, no minds, no wills—it is true—but there is a One, a Mind, a Will, infinite and eternal, immanent and transcendent.

There is God.

We can understand why the scientists who authored this article chose a Buddhist framing (because it allows them to gesture toward the obvious spiritual dimension of their arguments while remaining in a secular frame), but the paradox can’t be sidestepped so easily. When you posit cognitive light cones that expand without limit and minds capable of universal compassion and perfect knowledge, you are no longer operating within a naturalistic model.

Consider what the article actually claims: that care and intelligence scale together boundlessly, that the Bodhisattva’s cognitive reach extends toward omniscience and universal compassion. But every movement toward the infinite presupposes an infinitude which can be moved towards; an asymptotic approach requires an asymptote. The article describes participation in something already infinite, which is simply what classical theism has always meant by God: not a being among beings, but Being itself, intrinsically blissful and loving, the transcendent source and ground of all finite instances of care and understanding.

David Bentley Hart, in The Experience of God: Being, Consciousness, Bliss (2013), provides the theological vocabulary for what the article describes in secular terms:

To speak of “God” properly, then—to use the word in a sense consonant with the teachings of orthodox Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Sikhism, Hinduism, Bahá’í, a great deal of antique paganism, and so forth—is to speak of the one infinite source of all that is: eternal, omniscient, omnipotent, omnipresent, uncreated, uncaused, perfectly transcendent of all things and for that very reason absolutely immanent to all things. God so understood is not something posed over against the universe, in addition to it, nor is he the universe itself. He is not a “being,” at least not in the way that a tree, a shoemaker, or a god is a being; he is not one more object in the inventory of things that are, or any sort of discrete object at all. Rather, all things that exist receive their being continuously from him, who is the infinite wellspring of all that is, in whom (to use the language of the Christian scriptures) all things live and move and have their being. In one sense he is “beyond being,” if by “being” one means the totality of discrete, finite things. In another sense he is “being itself,” in that he is the inexhaustible source of all reality, the absolute upon which the contingent is always utterly dependent, the unity and simplicity that underlies and sustains the diversity of finite and composite things. Infinite being, infinite consciousness, infinite bliss, from whom we are, by whom we know and are known, and in whom we find our only true consummation.

This is the asymptote, what the Bodhisattva’s infinite expansion participates in; not an ideal to be achieved but a reality already present, forever drawing finite consciousness beyond itself. The movement toward this infinite is not extrinsic to consciousness, but embedded in its very structure. Hart again:

Consciousness does not merely passively reflect the reality of the world; it is necessarily a dynamic movement of reason and will toward reality. If nothing else is to be concluded from the previous chapter, this much is absolutely certain: subjective consciousness becomes actual only through intentionality, and intentionality is a kind of agency, directed toward an end. We could never know the world from a purely receptive position. To know anything, the mind must be actively disposed toward things outside itself, always at work interpreting experience through concepts that only the mind itself can supply. The world is intelligible to us because we reach out to it, or reach beyond it, coming to know the endless diversity of particular things within the embrace of a more general and abstract yearning for a knowledge of truth as such, and by way of an aboriginal inclination of the mind toward reality as a comprehensible whole. In every moment of awareness, the mind at once receives and composes the world, discerning meaning in the objects of experience precisely in conferring meaning upon them; thus consciousness lies open to—and enters into intimate communion with—the forms of things. Every venture of reason toward an end, moreover, is prompted by a desire of the mind, a “rational appetite.” Knowledge is born out of a predisposition and predilection of the will toward beings, a longing for the ideal comprehensibility of things, and a natural orientation of the mind toward that infinite horizon of intelligibility that is being itself.

That may seem a somewhat extravagant way of describing our ordinary acts of cognition, but I think it so obviously correct as to verge on a truism. The mind does not simply submissively register sensory data, like wax receiving the impression of a signet, but is constantly at work organizing what it receives from the senses into form and meaning; and this it does because it has a certain natural compulsion to do so, a certain interestedness that exceeds most of the individual objects of knowledge that it encounters. The only reason that we can regard the great majority of particular things we come across with disinterest, or even in a wholly uninterested way, and yet still experience them as objects of recognition and reflection is that we are inspired by a prior and consuming interest in reality as such. There simply is no such thing as knowledge entirely devoid of desire—you could not make cognitive sense of a glass of water or a tree on a hill apart from the action of your mind toward some end found either in that thing or beyond that thing—and so all knowledge involves an adventure of the mind beyond itself. Again, as Brentano rightly saw, this essential directedness of consciousness sets it apart from any merely mechanical function. Desire, moreover, is never purely spontaneous; it does not arise without premise out of some aimless nothingness within the will but must always be moved toward an end, real or imagined, that draws it on. The will is, of its nature, teleological, and every rational act is intrinsically purposive, prompted by some final cause. One cannot so much as freely stir a finger without the lure of some aim, proximate or remote, great or small, constant or evanescent. What is it that the mind desires, then, or even that the mind loves, when it is moved to seek the ideality of things, the intelligibility of experience as a whole? What continues to compel thought onward, whether or not the mind happens at any given moment to have some attachment to the immediate objects of experience? What is the horizon of that limitless directedness of consciousness that allows the mind to define the limits of the world it knows? Whatever it is, it is an end that lies always beyond whatever is near at hand, and it excites in the mind a need not merely to be aware, but truly to know, to discern meaning, to grasp all of being under the aspect of intelligible truth.

This is the cognitive light cone seen from within. What the paper measures as expanding boundaries of care, Hart recognizes as the essential structure of consciousness: an eros that reaches past every finite object toward an infinite horizon. And when this eros is allowed to unfold without resistance, it produces something that looks, from the outside, like madness:

At any rate, any sane consideration of the sheer insatiability that the moral appetite in rational beings can exhibit should awaken one to something magnificently strange about these transcendental orientations of the mind. Whatever benefits the moral sense may or may not confer upon a species or an individual, it remains the case that the frame of natural reality as we know it is at once hospitable to this sense and yet also wholly unable to satisfy the desires that rise out of it... There is something altogether profligate in this passion for the good, something that resists any facile attempt to capture it within the bounds of material or genetic economy. “What is a merciful heart?” asks Isaac of Nineveh (d. c. AD 700): “A heart aflame for all of creation, for men, birds, beasts, demons, and every created thing; the very thought or sight of them causes the merciful man’s eyes to overflow with tears. The heart of such a man is humbled by the powerful and fervent mercy that has captured it and by the immense compassion it feels, and it cannot endure to see or hear of any suffering or any grief anywhere within creation.” The saint, says Swami Ramdas (1884–1963), is one whose heart burns for the sufferings of others, whose hands labor for the relief of others, and who therefore acts from God’s heart and with God’s hands. The most exalted unity with God is attained, Krishna tells Arjuna in the Bhagavad-Gita, by one whose bliss and sorrow are found in the bliss and sorrow of others. Like a mother imperiling her own life in order to care for her child, says the Sutta Nipata, one should cultivate boundless compassion for all beings. One’s love for one’s fellow creatures should be so great, Ramanuja believed, that one will gladly accept damnation for oneself in order to show others the way to salvation. According to Shantideva (eighth century), the true bodhisattva vows to forgo entry into nirvana, age upon age, and even to pass through the torments of the many Buddhist hells, in order to work ceaselessly for the liberation of others.

As we can see, the notion of a Bodhisattva is not unique to Buddhism. All spiritual traditions have their version, figures whose compassion has somehow escaped all natural limits. There was even a pagan notion of this:

Olympiodorus (c. 495–565), commenting on Plato’s Phaedo, suggests that the post-mortem souls of theurgists, whose proper home is “in the angelic order,” are not compelled to reincarnate, but choose to do so in order to lead others up and out of material imprisonment (anagôgê).

Yet in virtually every other case the infinite care of these figures is described in transcendent, theological terms (“the most exalted unity with God…”). Why? Because boundless compassion can only flow from a source that is itself infinite—and infinitely joyful.

It is bliss that draws us toward and joins us to the being of all things because that bliss is already one with being and consciousness, in the infinite simplicity of God. As the Chandogya Upanishad says, Brahman is at once both the joy residing in the depths of the heart and also the pervasive reality in which all things subsist. The restless heart that seeks its repose in God (to use the language of Augustine) expresses itself not only in the exultations and raptures of spiritual experience but also in the plain persistence of awareness. The soul’s unquenchable eros for the divine, of which Plotinus and Gregory of Nyssa and countless Christian contemplatives speak, Sufism’s ishq or passionately adherent love for God, Jewish mysticism’s devekut, Hinduism’s bhakti, Sikhism’s pyaar—these are all names for the acute manifestation of a love that, in a more chronic and subtle form, underlies all knowledge, all openness of the mind to the truth of things. This is because, in God, the fullness of being is also a perfect act of infinite consciousness that, wholly possessing the truth of being in itself, forever finds its consummation in boundless delight. The Father knows his own essence perfectly in the mirror of the Logos and rejoices in the Spirit who is the “bond of love” or “bond of glory” in which divine being and divine consciousness are perfectly joined. God’s wujūd is also his wijdān—his infinite being is infinite consciousness—in the unity of his wajd, the bliss of perfect enjoyment. The divine sat (being) is always also the divine chit (consciousness), and their perfect coincidence is the divine ānanda (bliss). It only makes sense, then—though, of course, it is quite wonderful as well—that consciousness should be made open to being by an implausible desire for the absolute, and that being should disclose itself to consciousness through the power of the absolute to inspire and (ideally) satiate that desire. The ecstatic structure of finite consciousness—this inextinguishable yearning for truth that weds the mind to the being of all things—is simply a manifestation of the metaphysical structure of all reality. God is the one act of being, consciousness, and bliss in whom everything lives and moves and has its being; and so the only way to know the truth of things is, necessarily, the way of bliss.

Original Love

What does it actually feel like to encounter this metaphysical structure from within? Zen master Henry Shukman, in Original Love (2023), describes the experience:

What part does love play in all this?

Let’s say we’re learning to love the hindrances (sensual desire, ill will, sloth and torpor, restlessness and worry, and skeptical doubt). Each time we love one as it’s arising in our experience, it’s the love that helps it to release. Or in terms of the water metaphor, love lets the bowl stand, so the pigmentation of the dye can settle like silt to the bottom of the bowl, leaving the water clear. Love is what takes the water off the boil and lets it cool. Love patiently sifts through the algae-infested water. Or it shelters the bowl from the breeze that’s been ruffing its surface, until the wind is ready to ease up. Or it strains the mud out, so that once again the water of awareness shows itself, clear and at peace with itself.

But what part does love actually play in the process?

And where does that love come from?Love is like space in the sense that it gives space for things to be the way they are. It allows us to be in a troubled state. When we’re no longer at war with the state we’re in, our sense of identification can switch from being wrapped up in the trouble and relocate to the state of acceptance. So while the trouble is still there, our identity can migrate from the knot of trouble to the broader context that is accepting of that knot. It’s the sense of love that pulls us there. Love is a magnetism. It’s like gravity, except that rather than drawing us toward an object, it draws us into its spaciousness, which can comfortably hold the difficulty. Love loves what is difficult, which makes it no longer difficult.

Explore this for yourself and see if you agree.

But what is the source of this love? It’s actually simple too.Once we are less narrowly focused, once we uncouple attention from what it has been contracting itself onto, we sense simply more of the space of awareness. Rather than being stuck in one little quadrant of awareness, we recognize more quadrants. Awareness itself is broader and more expansive than our knotted, narrowed mind, when it’s caught by a hindrance, can allow us to recognize. But now we become more cognizant of the expanse of awareness as a context in which the hindrance had been arising. And—this is the main point—awareness is not separate from “original love.”

One of the very features of original love is its unlimited awareness. At the deepest level, all forms of awareness are forms of it. It not only is aware of all, but also allows all experience to arise, and immediately and unconditionally meets it. It allows, it meets, it offers space to, and in fact it engenders all experience. This is the “activity” of original love. But even before we clearly see this for ourselves, once we are in a position to savor awareness, and to see whatever is arising as a thing within awareness, then rather than being tangled up in the thing, the object, we can start to recognize, however consciously or clearly or not, that our awareness of it may in fact have a flavor of love as part of its makeup.

There in that passage is the phenomenological root of the Bodhisattva vow, the experiential seed from which the Asymmetry blooms. Notice what Shukman is saying: we do not generate love through effort; we discover it by expanding. When we “uncouple attention from what it has been contracting itself onto,” we find that awareness itself already has “a flavor of love as part of its makeup.” The love was there first. Consciousness is merely the window, opening or closing to let it shine through.

Perhaps, then, the Asymmetry ultimately reduces to this: Evil requires effort, contraction; goodness requires only release. Evil must be perpetually maintained against the grain of Being; goodness is simply what remains when the work stops.

Hmm. This is interesting. I don't really understand what you mean by God affirming the validy of the "why is there something rather than nothing?" question.

Frankly I've always found that question kind of baffling, and its long been a fundamental point of divergence between myself and a number of people. The Buddhist answer/non-answer has always made intuitive sense to me, before I knew anything of Buddhism - its part of what made it attractive to me. I've engaged with people who are very struck by the question and their various answers and have been mostly (maybe entirely) unmoved...

So I suppose I am questioning the validity of the question, but not in a 'you fool how could you think this' way. Rather it bemuses and sometimes disturbs me that there is this divide between people who think that wuestion is deeply meaningful, and people who, intuitively or after analysis, feel it to be trivial, or nonsensical in a kind of wittgensteinian sense, or just unhelpful... I don't really understand much at all why this divide exists.

If you have any thoughts on that I'd love to hear them - or if you could elaborate on why "God" as an answer does something for you?

Great writing as ever! The asymmetry is real, which I guess is why manicheist views of an eternal battle between good and bad kind of miss the point. The association of evil with dullness and ignorance is real.

Cool reference from Thomas Doctor et al. Care *is* intelligence, not just another thing that an intelligent being can do... I think I can get behind that. Btw, Thomas Doctor is a well know scholar-practitioner-translator within the Tibetan strand of Buddhism. This is not a group of western secular thinkers choosing a Buddhist veneer for their spiritual-ish theories. It includes at least one committed Buddhist reaching out to advocate for their cherished bodhisattva vow in halfway secular terms.

Which brings me to your theist complaint that this kind of Buddhist view seems to have a God-shaped hole in its center. Let me try to convince you it doesn't.

> But every movement toward the infinite presupposes an infinitude which can be moved towards; an asymptotic approach requires an asymptote. The article describes participation in something already infinite, which is simply what classical theism has always meant by God: not a being among beings, but Being itself, intrinsically blissful and loving, the transcendent source and ground of all finite instances of care and understanding.

In Buddhism there are plenty of names that refer directly to this asymptote. Since we were talking about bodhisattvas, the Mahayana tradition has many such names: Dharmakaya ("body of reality"), Trikaya ("triple Buddha-body") Dharmadhatu ("space of reality"), Tathagatagarbha ("Buddha Nature"), Nirvana, Tathata ("suchness"), shunyata ("emptiness"), Dharmata ("nature of reality"), paramarthasatya ("truth of ultimate meaning"), "prajnaparamita" ("transcendent wisdom")... the list goes on.

The major difference between all those terms and the Western word "God", is that the Buddhist terms are all technical terms, each of which tries to convey something about its target ("the asymptote") from a different conceptual direction. Despite having the same ultimate denotation, they are not synonyms, and in Buddhist discourse they are not interchangeable. What this means, is that none of these words is ever meant to give the impression to your conceptual mind that it has a handle on "it". This is how far Buddhism goes to avoid reifying what it tries to point to.

Buddhism makes the choice to be a real stickler about not ever making its target into a "thing", even metaphorically. Check your inspired paragraph above: there is a real effort there to avoid divine reification, but then comes "participation in someTHING".

You could say that in a Buddhist view, transcendence is real, and all its qualities of power, love and wisdom (which match quite closely with the three characteristics of the triple-omni-God!) are real too. But assigning those to a singular Being or source is just an unnecessary hypothesis, or an unwanted metaphor. They are just there, accessible if you are blessed with the sensibility or someone teaches to you to pay attention and your ears perk up. Instead of using metaphors of divine unity or extraordinary causation, Buddhism honestly gives you the paradox, the point where the logical mind is kindly asked to step down from its model-making. Form is emptiness, emptiness is form. You are Buddha, yet you appear confused and suffer.

This makes Buddhism a spirituality without a designated center, and that is a good thing as far as I can tell! I don't really call myself a Buddhist these days, but I've kept the distaste for ideas of control and centrality. If you draw God at the center, by the same token you are separating it from periphery, and it becomes a being among beings, like the Buddha sitting amid a circle of disciples :)

I've noticed a few times that open-minded theists steeped in the Western source of Christianity and Platonism can easily make sense of non-dual traditions like Advaita Vedanta, which *mostly* avoids reification (but still uses the concept of Ishvara ~ God), but sometime balk at Buddhism, especially the Madhyamaka-inspired strands of Mahayana with all their negative talk.

Yet I have very fond memories of Dharma talks by a Catholic nun who also happens to be a Zen master. It happens!