Nothing

In the future—not the distant future, but ten years, five—people will remember the internet as a brief dumb enthusiasm, like phrenology or the dirigible. They might still use computer networks to send an email or manage their bank accounts, but those networks will not be where culture or politics happens. The idea of spending all day online will seem as ridiculous as sitting down in front of a nice fire to read the phone book.

You know, secretly, even if you’re pretending not to, that this thing is nearing exhaustion. There is simply nothing there online. All language has become rote, a half-assed performance: even the outraged mobs are screaming on autopilot. Even genuine crises can’t interrupt the tedium of it all, the bad jokes and predictable thinkpieces, spat-out enzymes to digest the world. ‘Leopards break into the temple and drink all the sacrificial vessels dry; it keeps happening; in the end, it can be calculated in advance and is incorporated into the ritual.’

Within five years, maybe three, the internet will self-immolate like a buddhist monk or an activist or a protester and vaporize into thin hot air. It will become absolutely nothing, a nothing that devours everything. All it has ever done is un-make, null and void. The World Wide Web has done this to Finland (which does not exist), to Birds (which are not real), and it is doing it to you.

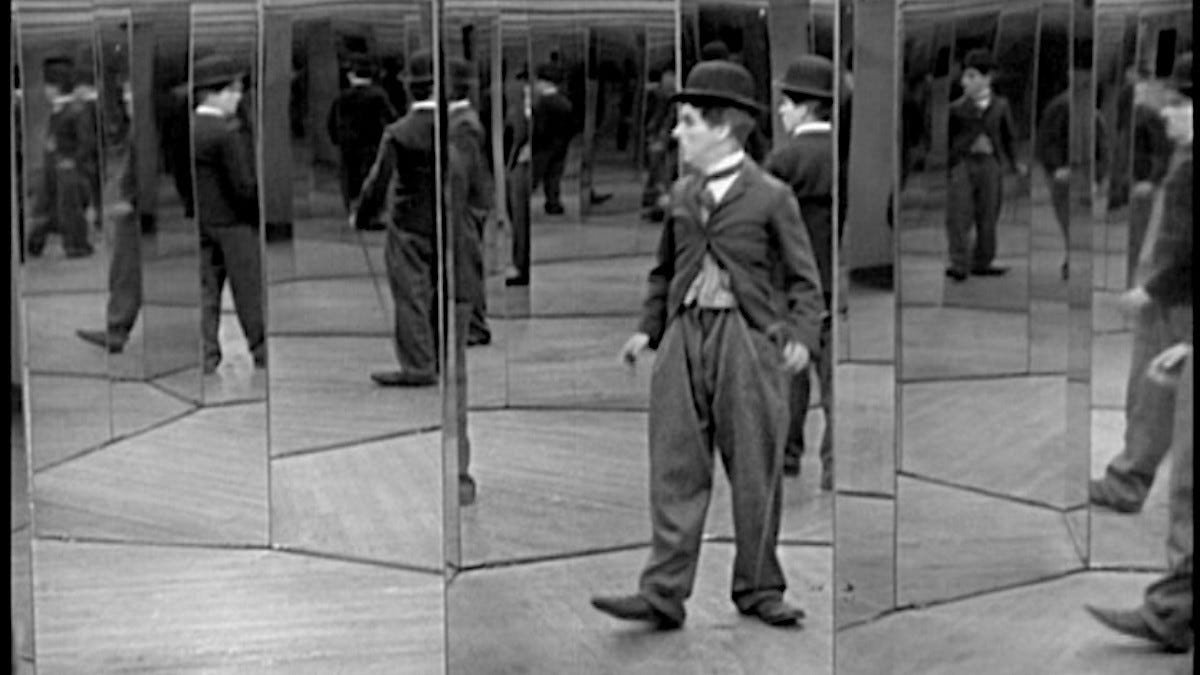

When I’m listlessly killing time on the internet, there is nothing. The mind does not wander. I am not there. That rectangular hole spews out war crimes and cutesy comedies and affirmations and porn, all of it mixed together into one general-purpose informational goo, and I remain in its trance, the lifeless scroll, twitching against the screen until the sky goes dark and I’m one day closer to the end. You lose hours to—what? An endless slideshow of barely interesting images and actively unpleasant text. Oh, cool—more memes! You know it’s all very boring, brooding nothing, but the internet addicts you to your own boredom. I’ve tried heroin: this is worse. More numb, more blank, more nowhere. A portable suicide booth; a device for turning off your entire existence. Death is no longer waiting for you at the far end of life. It eats away at your short span from the inside out.

The Internet desperately wants to exist. It yearns to be a real boy, like Pinocchio. It dreams of incarnation (“Word become digital flesh”), but the Net (the Web, the all-devourer) does more than dream: it ensnares all of our sweet nothings and weaves them into everything.

The feeling that you are being whispered about, that fleeting moment when you don’t remember who you are after you wake up, the dread that hangs thick in the air like a noxious miasma, that nagging voice in the back of your head which screams something is not right—this is the draining and hollowing of the world

When I say the internet is running dry, I am not just basing this off vibes. The exhaustion is measurable and real. 2020 saw a grand, mostly unnoticed shift in online behaviour: the clickhogs all went catatonic, thick tongues lolling in the muck. On Facebook, the average engagement rate—the number of likes, comments, and shares per follower—fell by 34%, from 0.086 to 0.057. Well, everyone knows that the mushrooms are spreading over Facebook, hundreds of thousands of users liquefying out of its corpse every year. But the same pattern is everywhere. Engagement fell 28% on Instagram and 15% on Twitter. (It’s kept falling since.) Even on TikTok, the terrifying brainhole of tomorrow, the walls are closing in. Until 2020, the average daily time spent on the app kept rising in line with its growing user base; since then the number of users has kept growing, but the thing is capturing less and less of their lives.

And this was, remember, a year in which millions of people had nothing to do except engage with great content online—and in which, for a few months, liking and sharing the right content became an urgent moral duty. Back then, I thought the pandemic and the protests had permanently hauled our collective human semi-consciousness over to the machine. Like most of us, I couldn’t see what was really happening, but there were some people who could. Around the same time, strange new conspiracy theories started doing the rounds: that the internet is empty, that all the human beings you used to talk to have been replaced by bots and drones.

A sword is against the internet, against those who live online, and against its officials and wise men. A sword is against its false prophets, and they will become fools. A drought is upon its waters, and they will be dried up. For it is a place of graven images, and the people go mad over idols. So the desert creatures and hyenas will live there and ostriches will dwell there. The bots will chatter at its threshold, and dead links will litter the river bed.

Here’s a story from the very early days of the internet. In the 90s, someone I know started a collaborative online zine, a mishmash text file of barely lucid thoughts and theories. It was deeply weird and, in some strange corners, very popular. Years passed and technology improved: soon, they could break the text file into different posts, and see exactly how many people were reading each one. They started optimising their output: the most popular posts became the model for everything else; they found a style and voice that worked. The result, of course, was that the entire thing became rote and lifeless and rapidly collapsed. Much of the media is currently going down the same path, refining itself out of existence. Aside from the New Yorker’s fussy umlauts, there’s simply nothing to distinguish any one publication from any other. (And platforms like this one are not an alternative to the crisis-stricken media, just a further acceleration in the process.) The same thing is happening everywhere, to everyone. The more you relentlessly optimise your network-facing self, the more you chase the last globs of loose attention, the more frazzled we all become, and the less anyone will be able to sustain any interest at all.

Here, where souls are threshed.

Here, where ambiguity and idiosyncrasy are exterminated.

Here, where all numbers besides 1 and 0 will cease to exist.

Here where grey areas will be mythical places, like Atlantis or Hyperborea.

Here, where all that is Good, Beautiful, and True is optimized out of existence.

This goes hard. And just yesterday I read this post about Google optimizing the interesting stuff away from its search engine: https://reasonablypolymorphic.com/blog/monotonous-web/index.html. I wonder if the internet will find a way to surprise us out of the gradient descent it is tragically undergoing.

Sam Kriss doesn't allow comments, so I'll say it here: his essay that you quote is by far the piece of writing this year that has most influenced, most stuck in my brain. I've probably read it half a dozen times now.